- {{ item.label }} {{ item.address }}

In the field of architecture and urban history, we are yet to unravel the impact of Switzerland’s entanglements with global colonialism on the built environment, and, more widely, on the aesthetic, material and craft cultures of Swiss cities.

To unravel these often indirect entanglements, the term coloniality is a particularly salient term: it refers to the long-lasting processes and indirect effects that are the result of centuries of colonialism, and that mark a landscape of global inequality, even after the ‘official’ reign of colonialism has ended. So, despite being a country without colonies, what if we consider Switzerland’s architectural and urban history from the perspective of this historical inequality? What is the specific architectural and urban dimension of Swiss coloniality?

Each semester, our Research Studio is zooming in on one specific kind of infrastructure that acted as support for global colonialism – from the straightforward tangible infrastructure of trade routes, ships, outposts and plantations, to more

subtle and intangible infrastructures such as mission work, science and other forms of knowledge production. The economic realm is by far the most obvious place to start this investigation, and the role of industry in particular – with its extraction of raw materials and production of goods to be traded on markets – offers a hands-on approach to unravel its entanglement with architecture and the built environment.

In our Autumn 2023 studio, students investigated this industrial infrastructure from architectural, urban typological, environmental and material perspectives. How did, for instance, the chocolate or textile industry shape the built environment of Switzerland through its factories and warehouses, its trade routes, or housing projects for its laborers? How did architecture itself become part of an industry that was exported abroad, through its building materials, its technology or its expertise? And how was a colonial-fed industry represented and symbolized in the Swiss cityscape?

Mission-Made Kannur?

Project by Deepthi Puthenpurackal

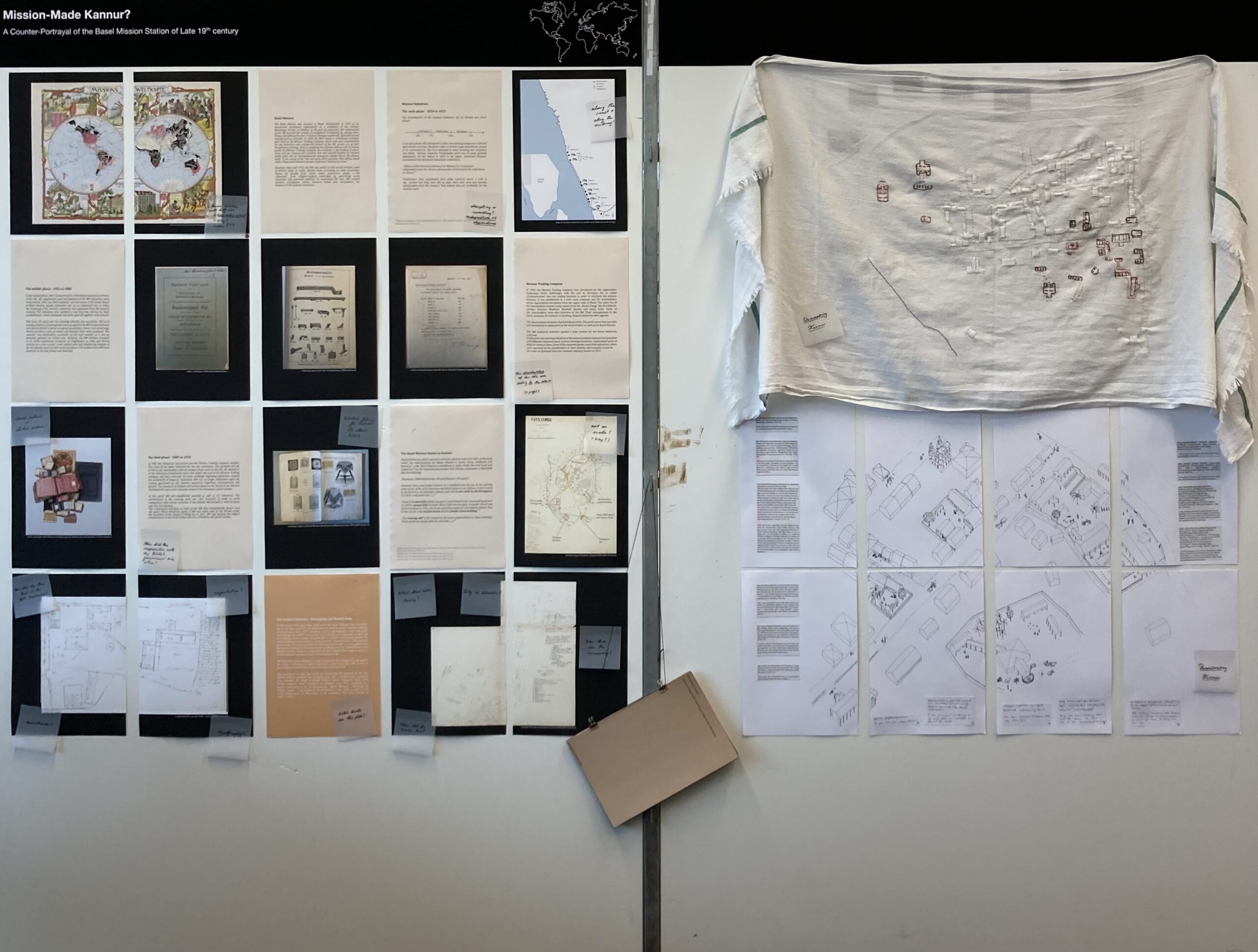

Mission-Made Kannur? A Counter-Portrayal of the Basel Mission Station of late Nineteenth Century

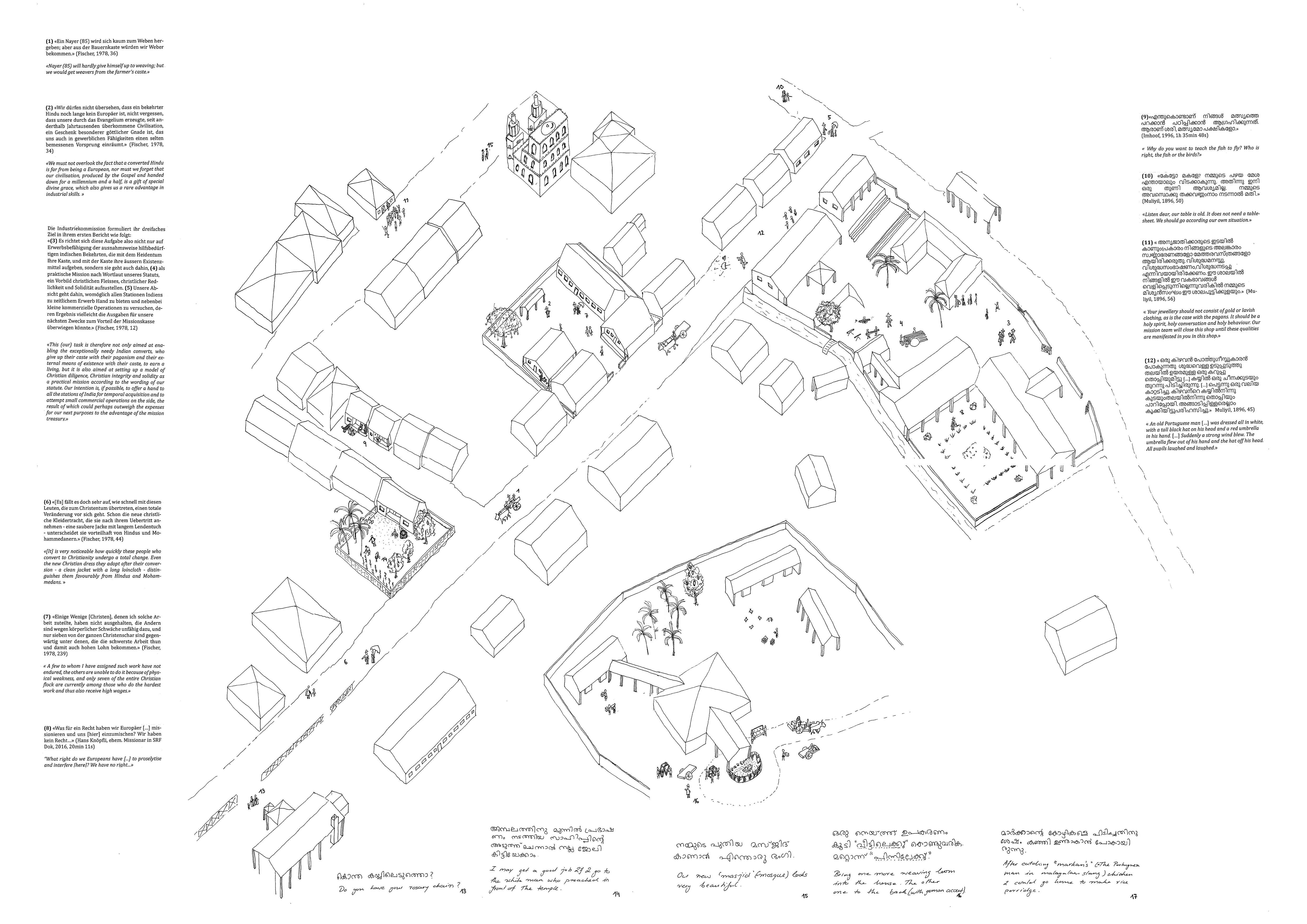

The Basel Mission, established in 1815 in Basel as an ecumenical missionary organization, operated in several African and Asian countries with the primary goal of propagating Evangelical Christianity. Central to their ideology was the promotion of a Western idea of labor and discipline.

When their conversion efforts started in South India in 1834, the Basel Mission encountered the Hindu caste system. For the new Christians, conversion was an ambivalent situation: on the one hand, they were “liberated” from caste-related constraints, while on the other, leaving Hinduism also meant the loss of all possessions, including their social network and occupation. To address this issue, the Basel Mission initiated the establishment of various commercial institutions, including industries, providing the “Heidenchristen” with an alternative source of income.

The mission’s entrepreneurial success was mirrored in the establishment of several industries, such as weaving mills, and international export of products, such as textiles. Fabrics could not only be exported across the entire British Empire but also generated a new market for Swiss industrial products: weaving looms, spare parts, and chemical dyes from Switzerland found a new market in the South Indian mission compound of Kannur.

Some of these Swiss industrial export companies were, in fact, owned by the shareholders of the Mission Trading Company.

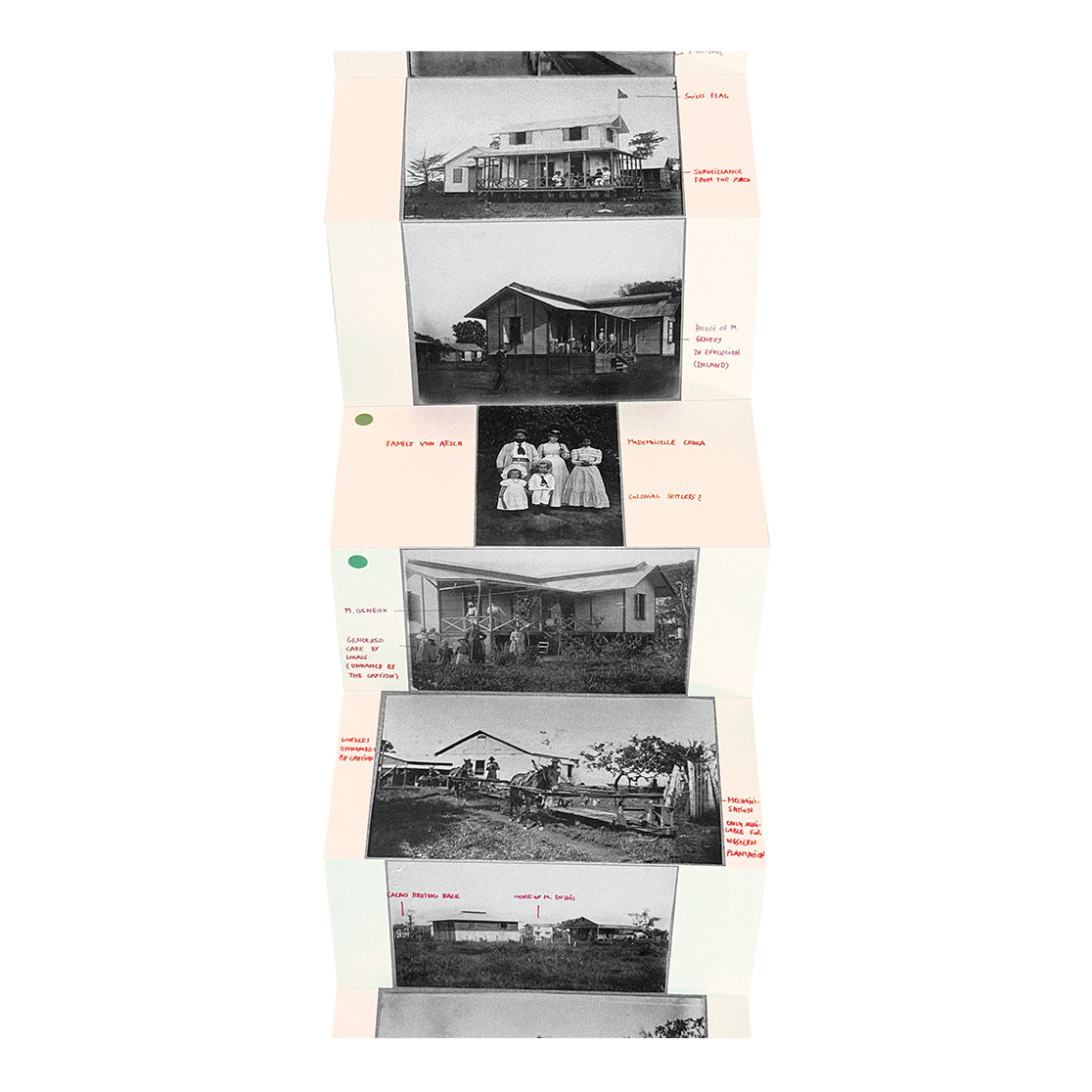

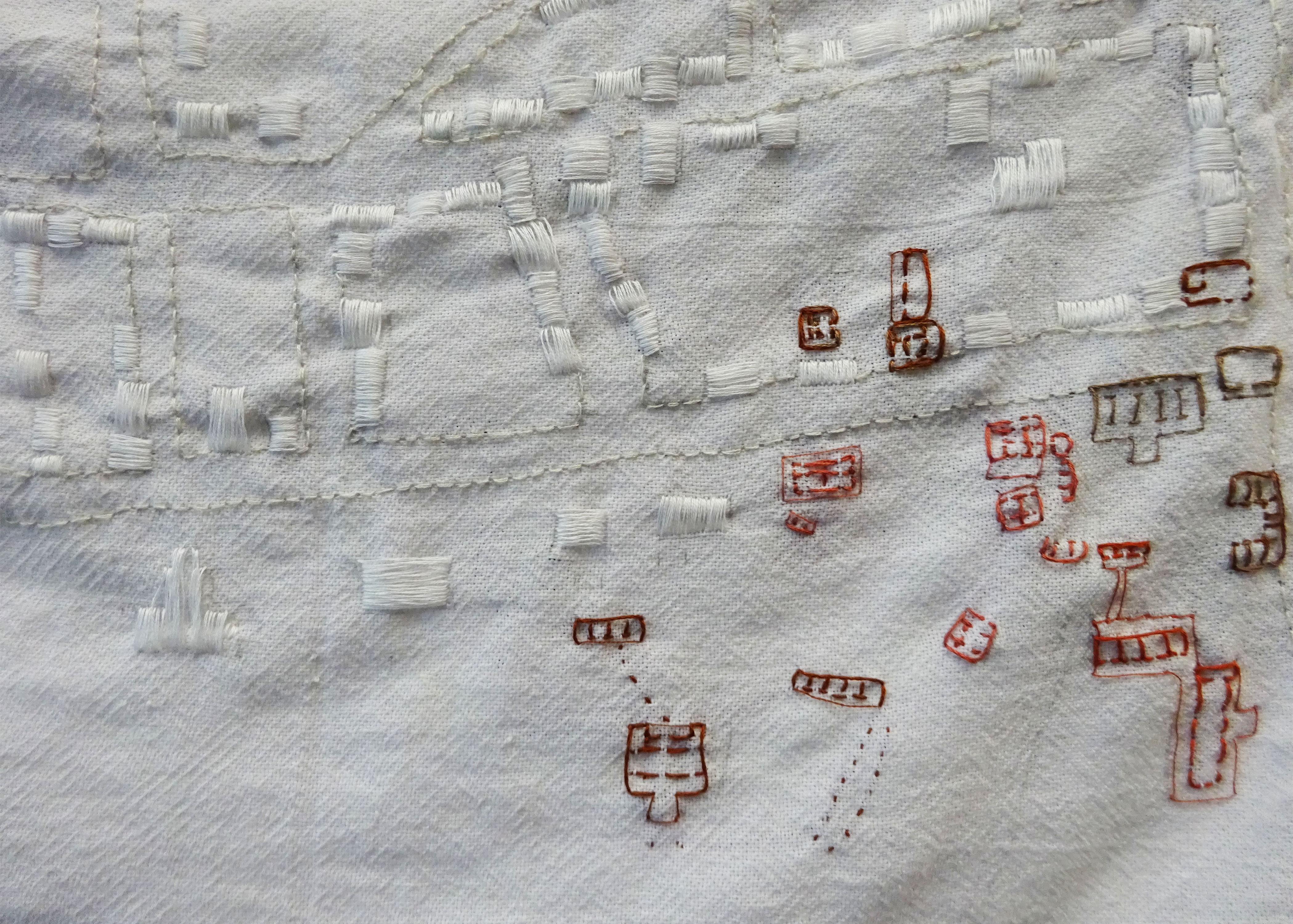

The history of the organization is documented in the Basel Mission archive, which contains holdings dating back to 1815 including reports, photographs, maps, and plans. Even though the archive is very rich in its quantity, I started to ask myself questions to which I could not find clear answers. For instance, who lived in the area surrounding the Basel Mission compound? What was life like there? Where are the documents showing native livelihoods?

The archive’s selectivity, influenced by editorial policies and consensus within the Basel Mission, determined the content and preservation of the Mission’s materials. In an architectural and artistic way, I addressed these gaps and created a fabulated recreation of the neighborhood by drawing, mapping, and embroidering, aiming to tell a new, yet old, story; a story that cannot be found in the archive. Next to material in the archive, I based my work on the 1897 Malayalam novel Sukumari by Joseph Muliyil, Markus Imhoof’s movie Flammen im Paradies from 1996, comments of a former missionary in the SRF documentary Basler Mission from 2016, and discussions at the conference “The Basel Mission in India” in 2023. Based on these sources, I added my own critically fabulated narrative.

The Honegger Brothers and the “Système HA”

Project by Lionel Scherz

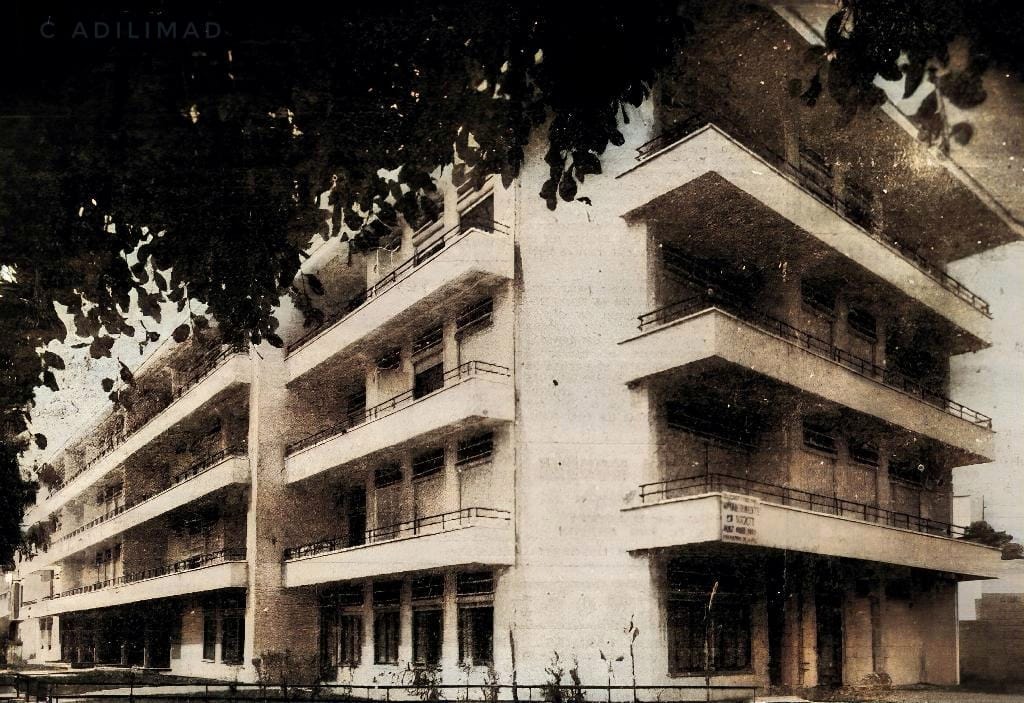

The Honegger Brothers and the “Système HA” – Casablanca and Geneva: a Prefabricated Concrete Floor System

The three Honegger brothers—Jean-Jacques, Pierre, and Robert—greatly influenced the urban development of Geneva and the surrounding area, constructing together more than 9,000 homes. They were introduced to architecture by their father, Henri Honegger, in the 1930s. Henri was a property manager and close associate of Maurice Braillard, an influential architect and town planner in Geneva. After collaborating with the architect Louis Vincent, the brothers founded their own firm, Honegger-Frères, venturing into the use of modern construction techniques. While building commissions were low during the economic crisis and the war, they expanded their networks in architect associations such as CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) and GANG (Groupe d’Architecture Nouvelle à Genève).

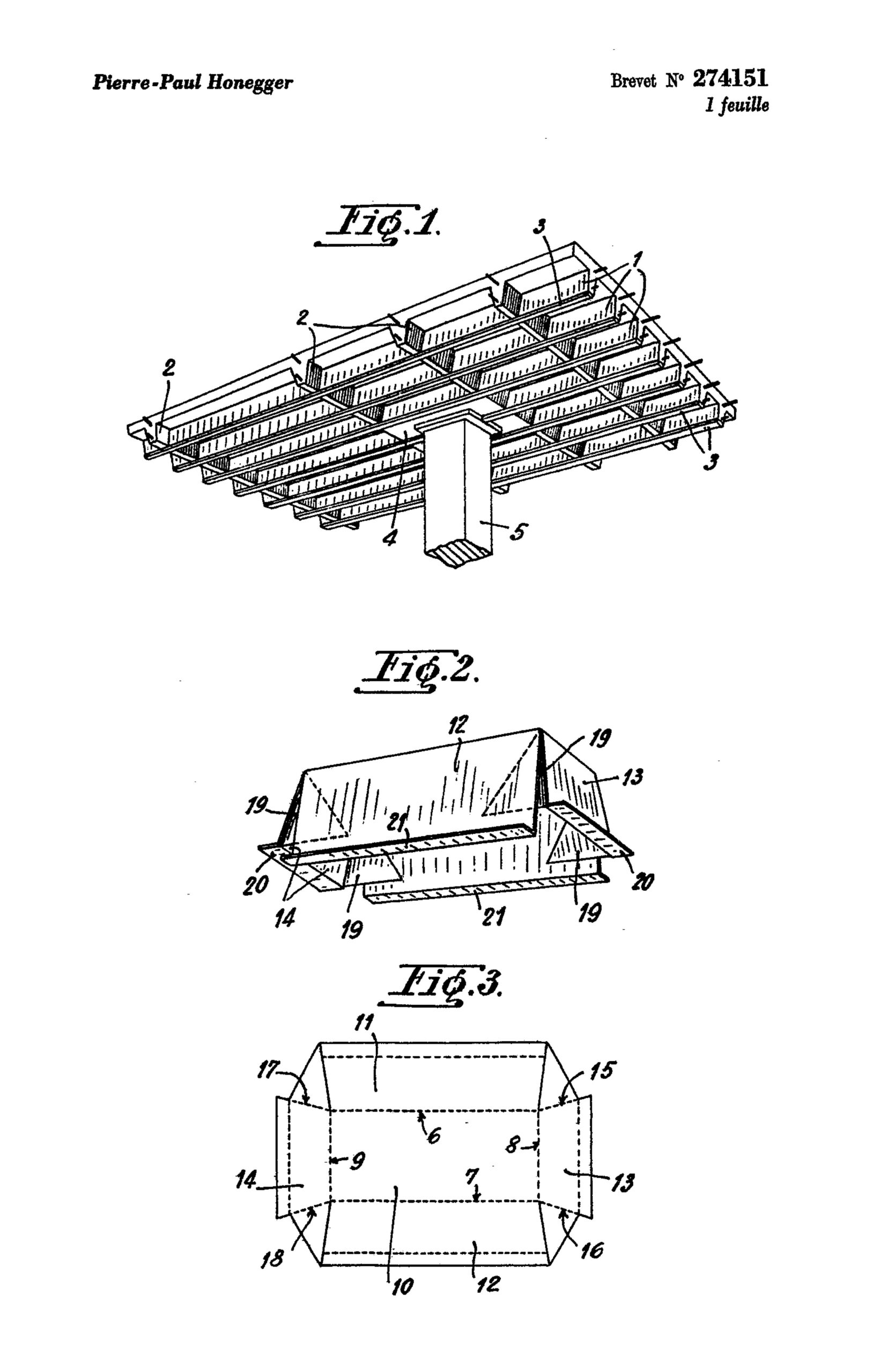

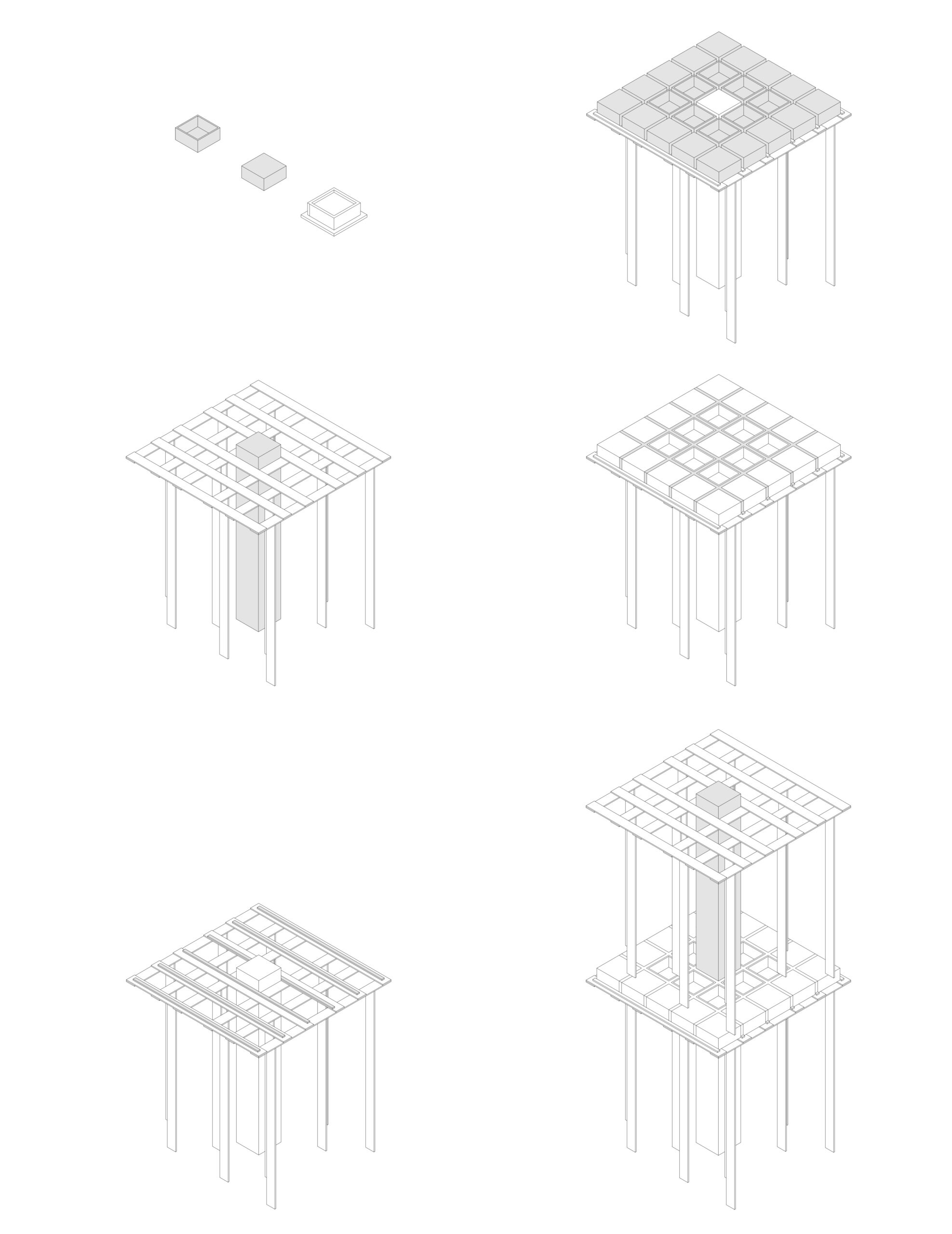

After the war, they set up a new office in Geneva in 1947 and began using prefabricated components, at which point an acquaintance invited them to Casablanca. There they founded a company that would operate a patent for constructing cross-ribbed slabs with an easily reusable formwork made of sheet metal. Not satisfied with their first building experience in using this construction method, they refined their idea of rectangular formwork and turned it into prefabricated concrete boxes.

Manufactured in the workshop and installed on site, this system saves a considerable amount of time. The first step is to install wooden props, followed by prefabricated reinforced concrete joists. Between these joists, the concrete caissons are installed. Reinforcement is then placed between the spaces around the caissons and the concrete is poured. Without having to wait for the concrete to dry, the installation of the upper floor can begin.

They improved their system to rationalize construction and material costs as much as possible, and came up with their 60cm-by-60cm caisson system, the “système Honegger-Afrique” or “système HA.” Using this system, they built a number of buildings in parallel in Geneva and Casablanca, before leaving Morocco in 1956 following the country’s independence.

By testing different structural systems in Casablanca and using their own experience in Geneva, they devised a recognizable architectural and constructive language. Economical, adaptable to all contexts and programs, and with a rapid execution speed, their system was a great success. In Geneva, the size and number of their buildings increased considerably until the 1970s, when prefabrication techniques changed and their system did not survive. Around the same time, the three brothers retired and the office passed into the hands of their children. With more than 9,000 homes built, the Honegger brothers have left a lasting mark on the city of Geneva and its inhabitants.

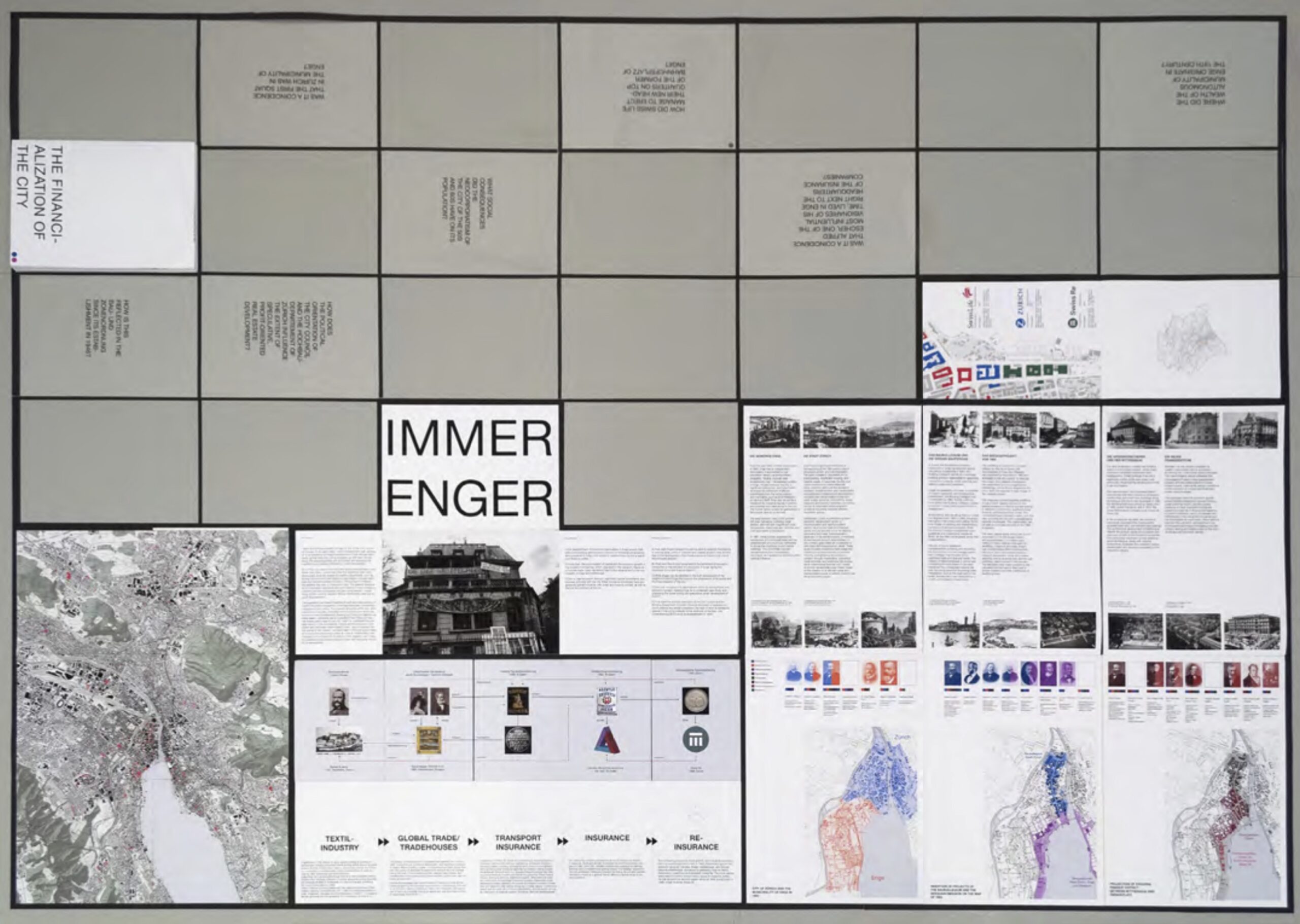

Immer Enger

Project by Nora Hochuli

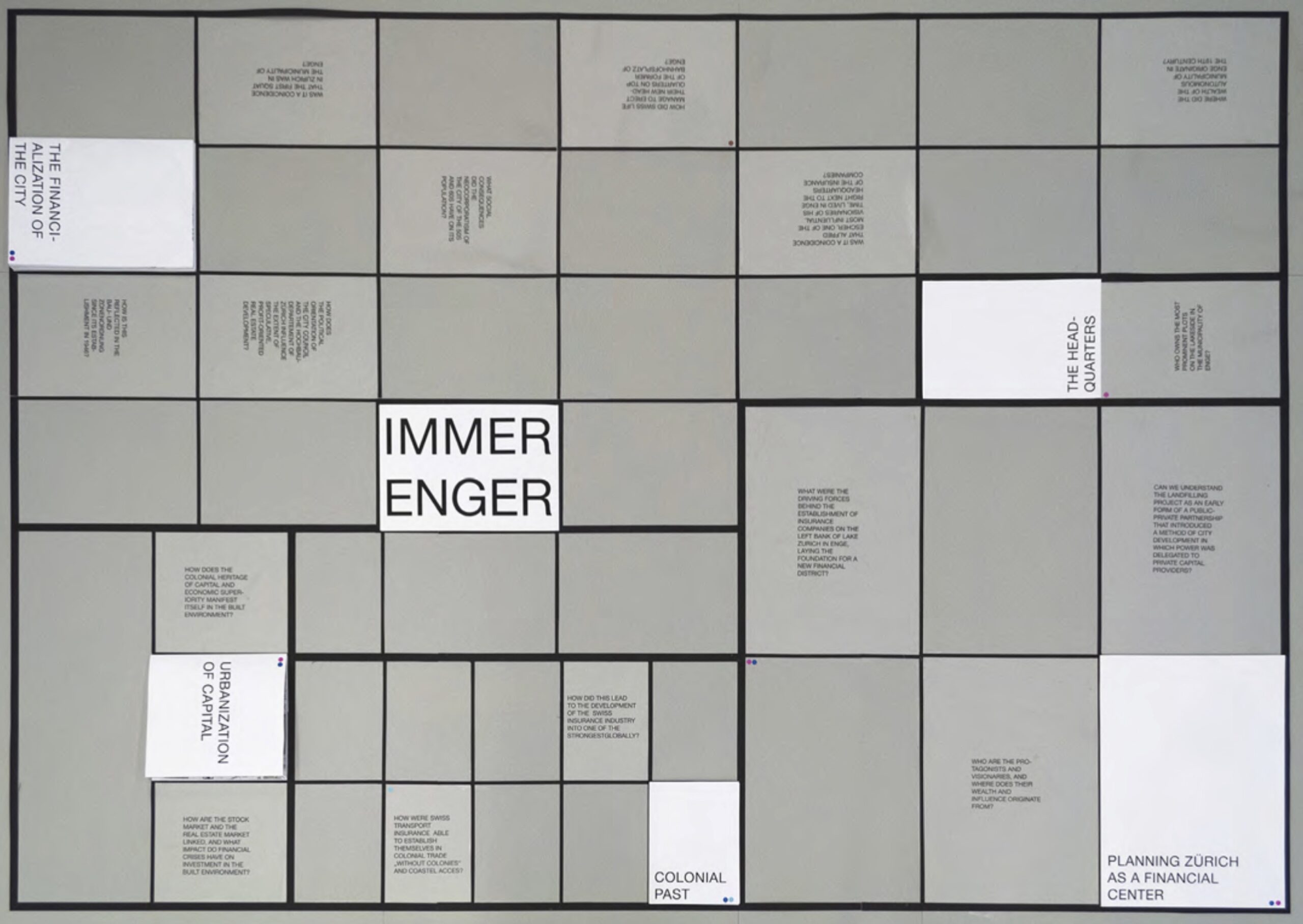

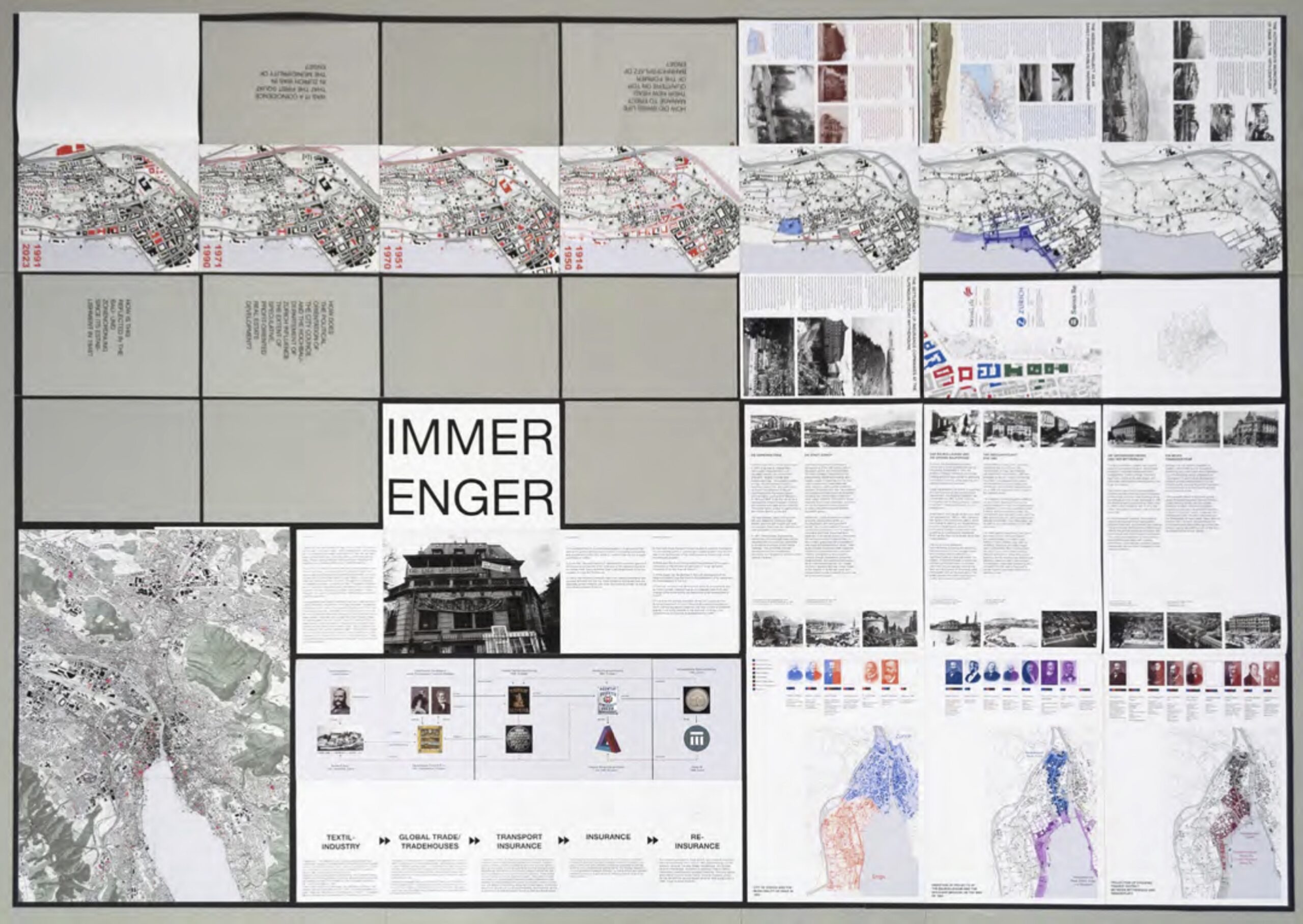

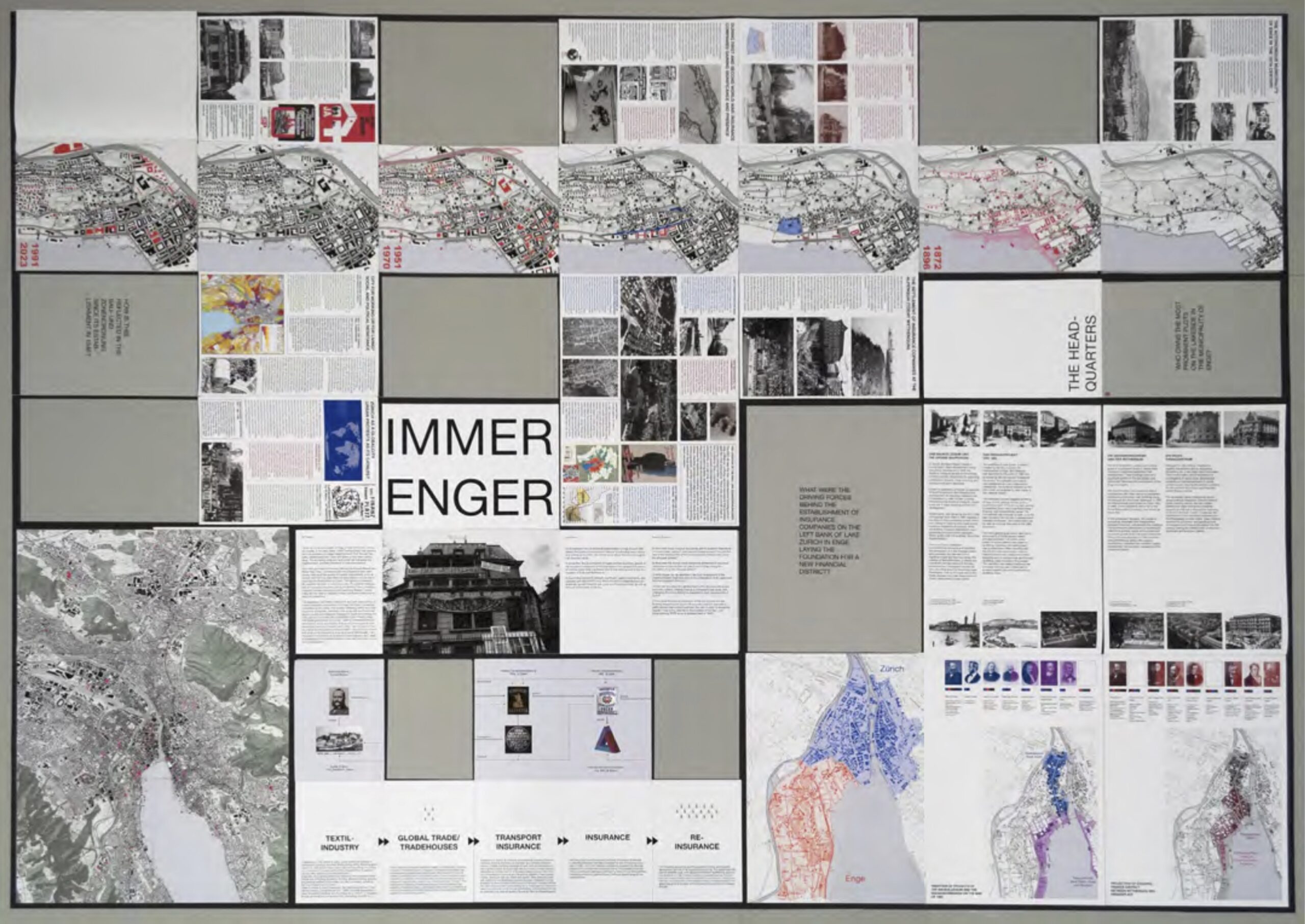

Immer Enger: The Urbanization of Capital and the Financialization of the City – The Case of Zurich’s Insurance Companies

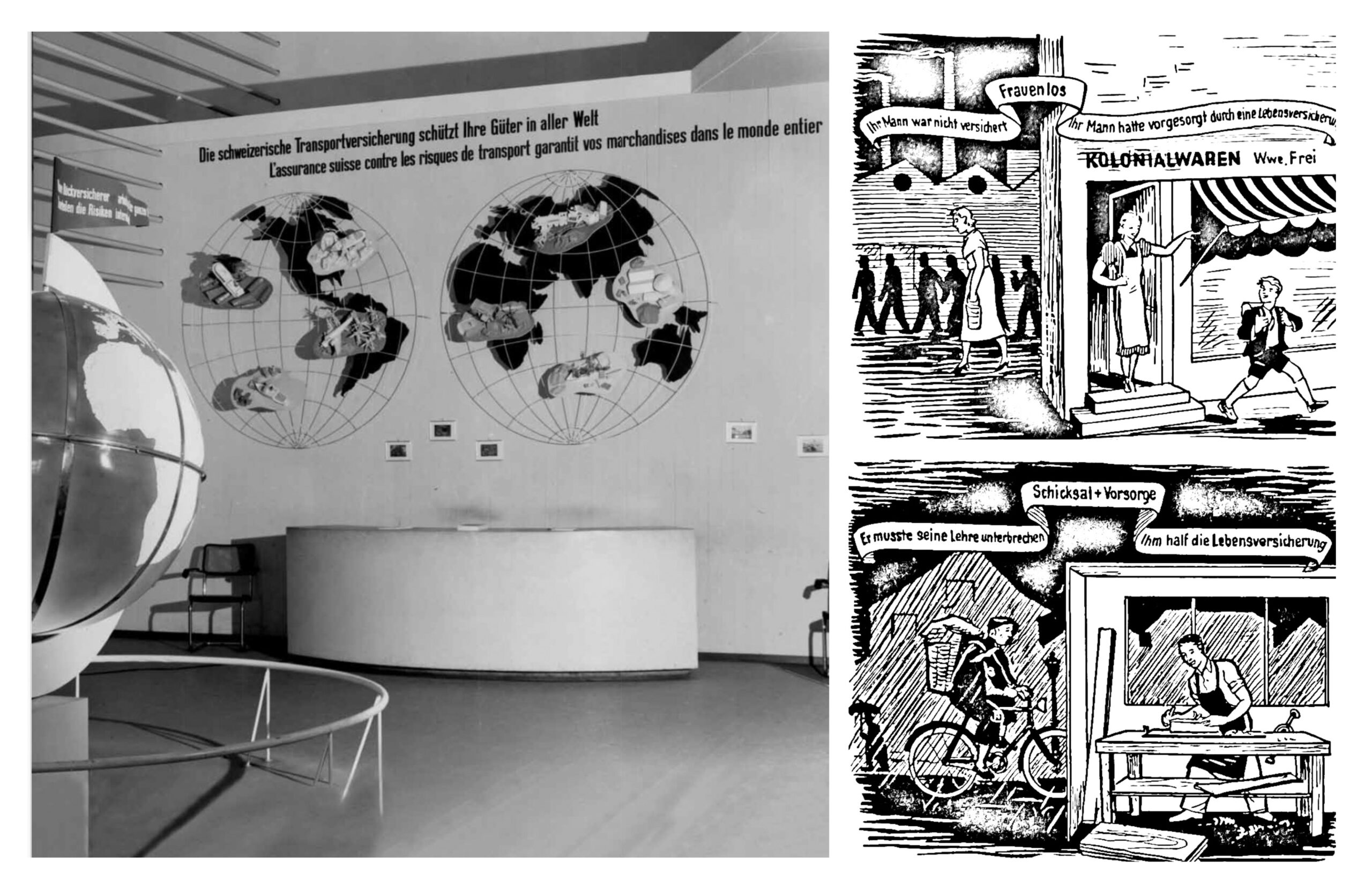

My study delves into Zurich’s insurance sector, tracing its evolution from colonial times to its role in shaping Zurich into a financial hub in the nineteenth century, and its contemporary impact on the city’s built environment and urban housing policies.

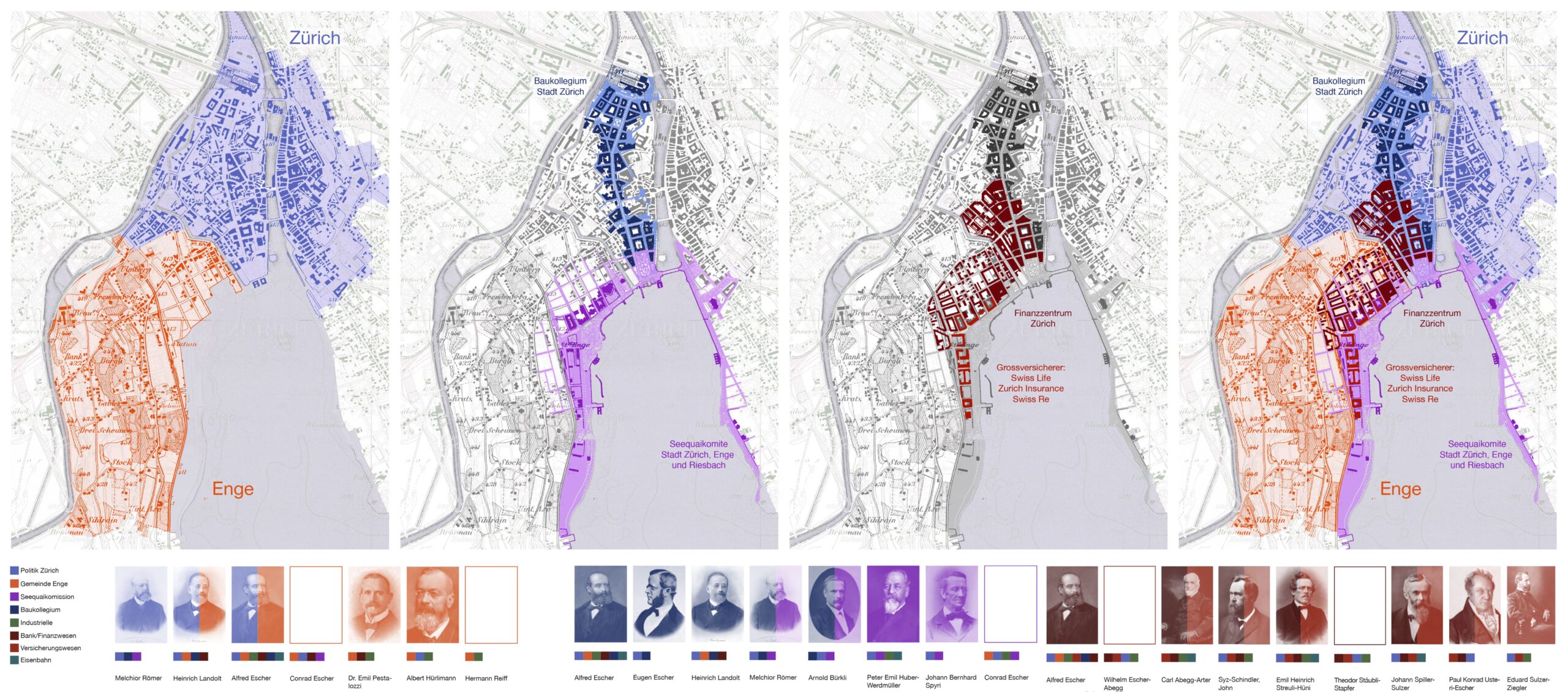

The origins of Swiss insurance companies lie in transport insurance firms established by wealthy Swiss textile industrialists and merchants. Their purpose was to insure ships transporting trade goods, whether for importing colonial goods or exporting products to colonies. These entrepreneurs leveraged their trade networks to distribute insurance globally. [1] As speculation and high profits made the insurance industry lucrative, the insurance industry boomed and other insurance branches soon followed, including reinsurance companies that insured the insurers themselves. This development led to significant value creation, with enormous capital flowing back to Switzerland. Today, Switzerland is one of the most well-insured countries in the world, home to some of the largest insurance companies worldwide.

Around 1900, the three major insurers (Swiss Life, Swiss Re, and Zurich Insurance) established themselves on the left bank of Lake Zurich, at Mythenquai in the municipality of Enge, as an integral part of the Seequai project, which manifested Zurich’s stature as a commercial and financial center. [2] The newly landfilled lake basin provided prime real estate for the insurers’ headquarters, creating fertile ground for a new financial sector, nestled between a prosperous quarter of merchants and industrialists and a growing city. In exchange, the landfilling was partly cross-financed by the new landowners. It is noteworthy that the involved visionaries often simultaneously operated as industrialists and merchants, in politics, and in the banking and insurance sector. [3]

This early example of a public–private partnership marked the beginning of a city policy where Zurich relied on financial support from big insurance companies to realize urban projects. Zurich’s insurance companies are among the largest real estate investors globally and have not only gained increasing influence over the city’s built environment but also over urban and housing policies. The development of the Enge district since the establishment of the major insurers can be seen as a condensed example illustrating processes of capital urbanization and the financialization of the city.

Their strong presence and high level of investments have significantly impacted the area, demonstrating a direct correlation between the companies’ development and their physical neighborhood. Through capital-intensive land speculation, not only have rental and land prices increased, but residential spaces have also been replaced by service and office facilities.

These displacement processes have led to social conflicts and gentrification but also provoked a housing movement that emerged in Zurich in the 1970s. Was it, for instance, a coincidence that Zurich’s first house occupation occurred in the Enge district? The slogan “Die Enge wird immer Enger,” which became the motto of the Venedigstrasse occupation, drew attention to the economically profitable replacement of residential space with service space and emphasized that the city council protected capital interests over the needs of its inhabitants. Seven residential houses were replaced by an office complex housing the Schweizerische Lebensversicherung (today’s Swiss life). [4]

Today, Zurich is once again facing a housing crisis, caused by ongoing urbanization processes and profit-oriented land and real estate speculation by large investors, still raising the same question: is Zurich a place for working or a place for living?

Suchard’s Architectural Production

Project by Rémi Madrona

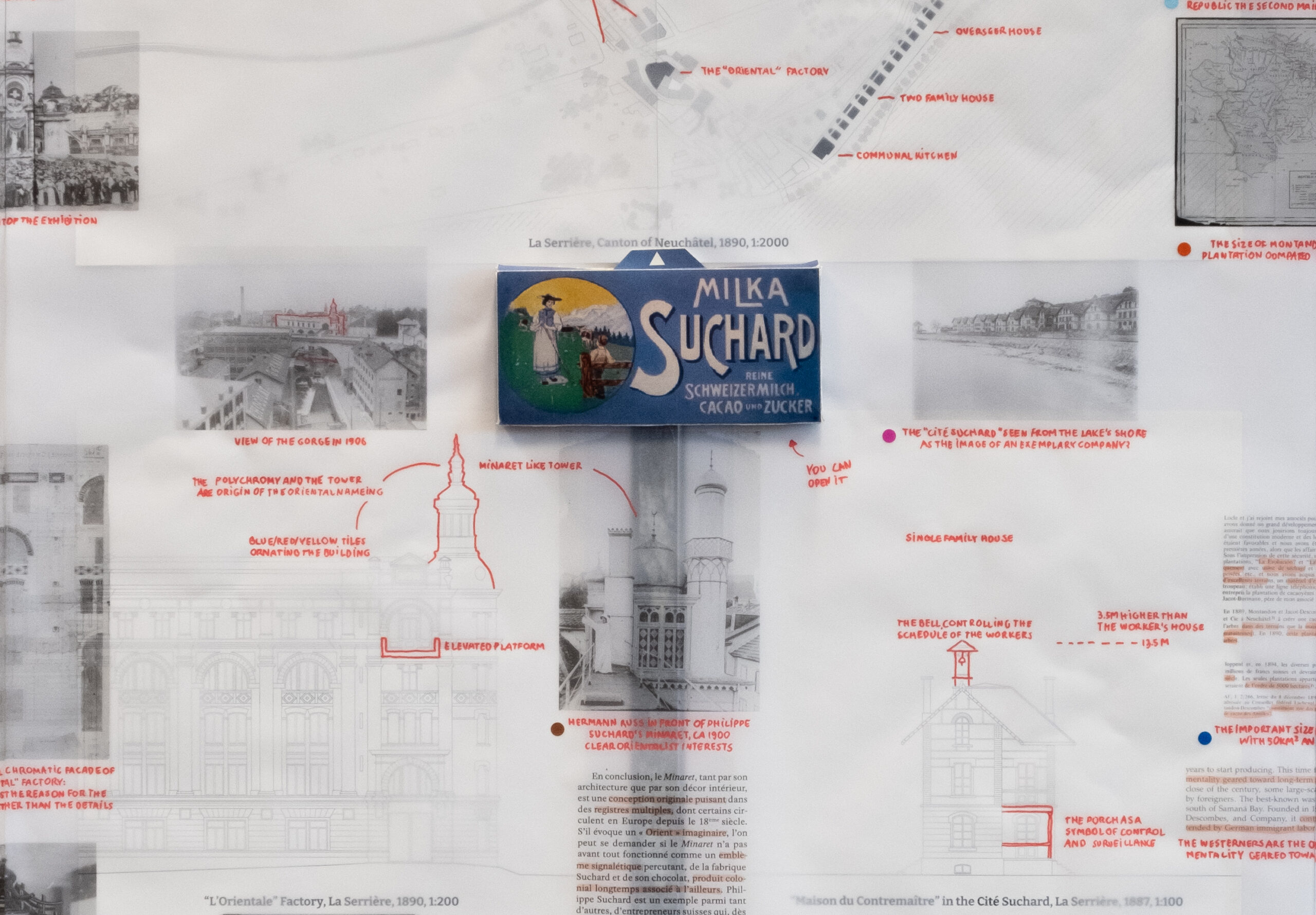

Suchard’s Architectural Production: The Ideologies of a Swiss Chocolate Empire at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

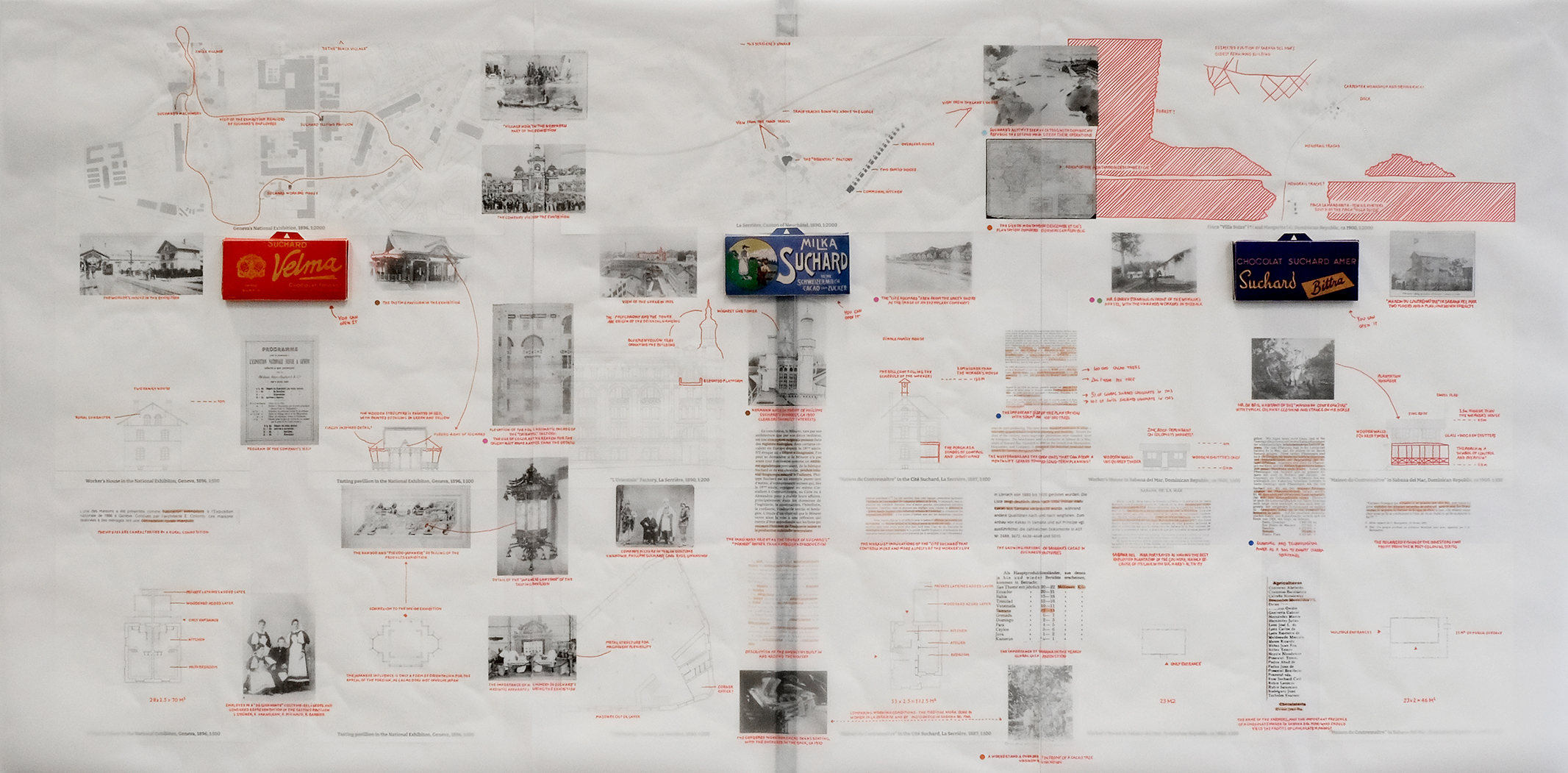

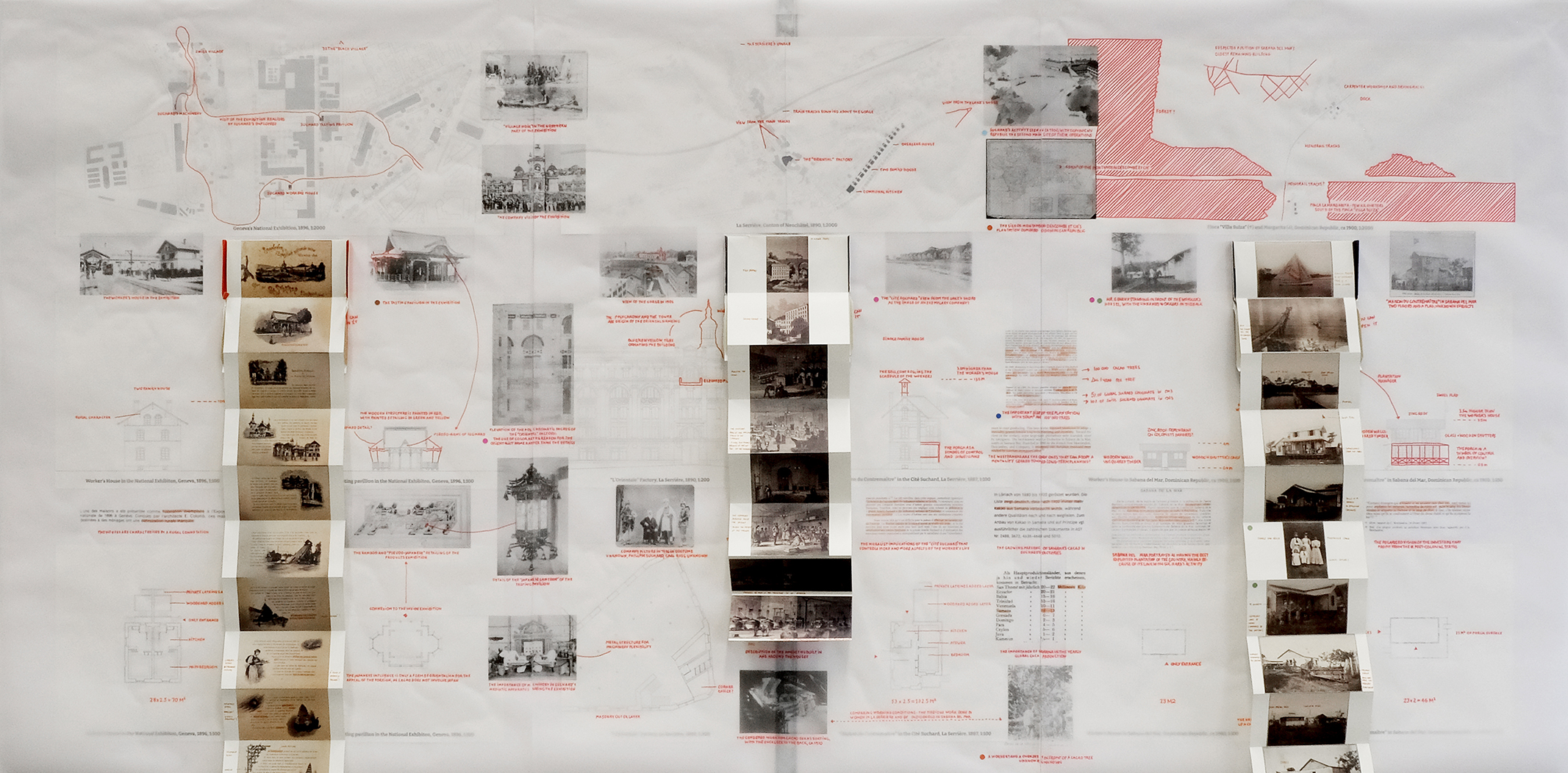

Examining Swiss chocolate through the lens of the Suchard chocolate company reveals a narrative intertwined with colonialism. Founded in 1826 by Philippe Suchard, the company’s success expanded after winning prizes at the 1851 London Great Exhibition and the 1855 Paris Universal Exposition. Through innovative marketing, particularly the distinctive purple branding of Milka chocolate since 1901, Suchard established itself as one of the biggest chocolate manufacturers at the turn of the twentieth century.

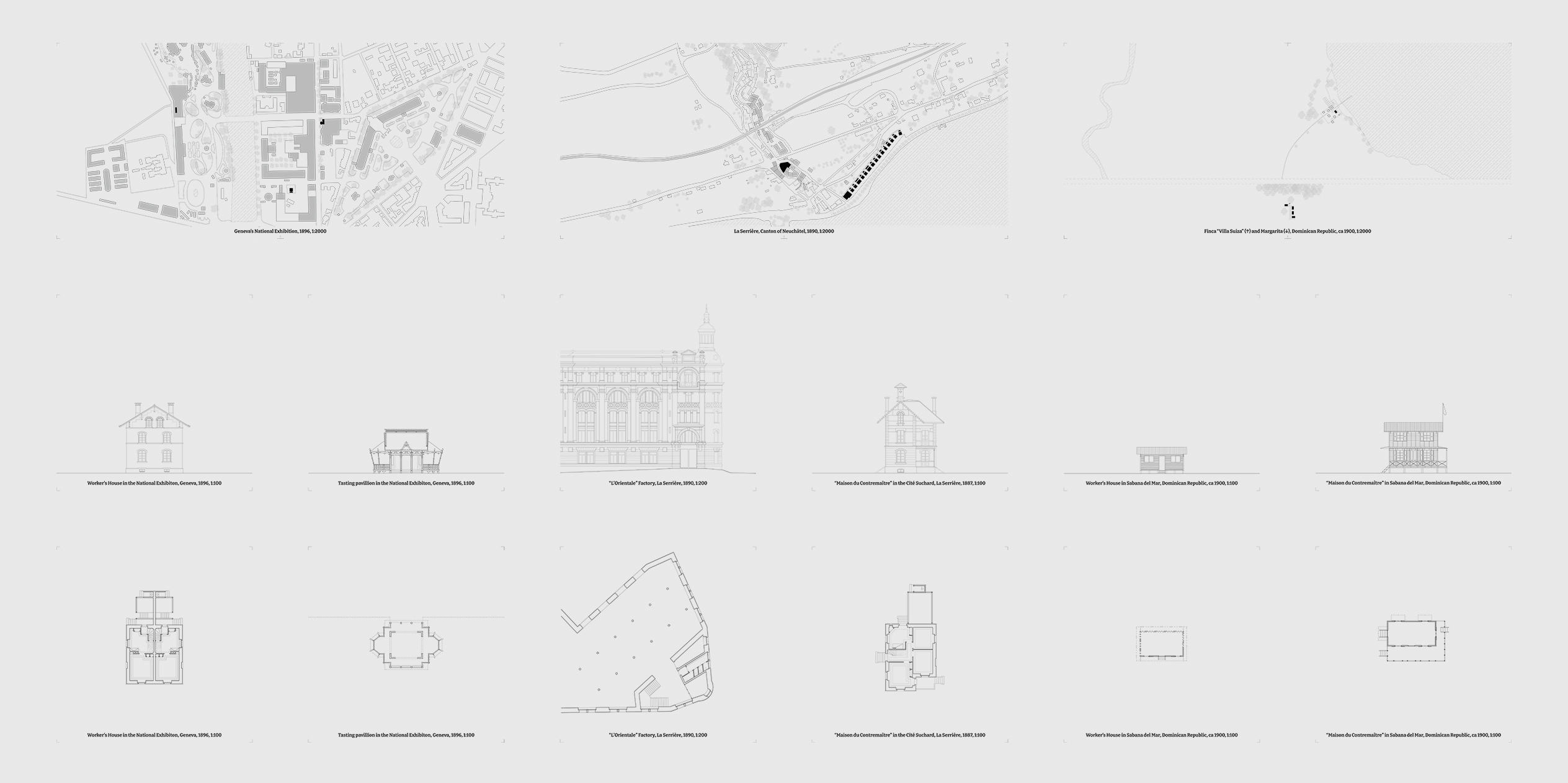

By examining Suchard’s architectural footprints across three locations—Geneva’s pavilions, Neuchâtel’s factory and worker housing, and the plantation in Sabana del Mar, Dominican Republic—this project brings the company’s colonial and paternalistic ideologies to light.

Firstly, in the gorge of La Serrière near Neuchâtel, the Industrialist Philippe Suchard capitalized on the powerful river of the same name as the energy source for its machinery. One of the selected case studies is the “L’Orientale” factory built in 1890, based on orientalist inspiration.

Due to the cramped context of the gorge, housing conditions became unsanitary, which led to the construction of the “Cité Suchard.” The various multi-family and single-family typologies accompanied by a communal kitchen and laundry room, as well as playgrounds and private gardens, represent one of the best examples of the workers’ town in Switzerland.

Secondly, in Geneva, the 1896 National Exhibition showcased Swiss products on the global stage, with Suchard presenting a reconstructed worker’s house from Cité Suchard, machinery, and a chocolate-tasting pavilion. The latter, built in a “pseudo-Japanese” [1] style, catered for bourgeois comfort and symbolized colonial luxury.

Lastly, Sabana del Mar presents a darker aspect of Suchard’s legacy. Suchard trader Carl Russ’s late nineteenth-century investment in cocoa plantations represented a significant portion of the company’s cocoa processing. Despite limited archival material, research into local newspapers, legal documents, and narratives reveals the plantation’s scale as “one of the largest, if not the largest Cacao plantation in the Caribbean” [2]. The study focuses on the plantation’s reconstructed layout, the foreman’s house, and worker housing, highlighting the racial and social disparities enforced through architectural choices.

Paternalism is evident in Suchard’s company housing across different geographies. In Neuchâtel, workers’ houses blend bourgeois and rural styles, with the foreman’s house standing out with its elevated veranda symbolizing control. The opportunity of accessing housing is nuanced by the fact that the “workers risk losing [their] social advantages if leaving the company” [3]. Sabana del Mar mirrors this hierarchy with a larger, higher-quality foreman’s house. Racial disparity is evident in the materials used, with the white population enjoying squared timber and glass windows, while local workers were limited to wooden shutters and lesser-quality materials. Suchard’s architectural choices for its buildings reflect its paternalistic approach and hierarchical structures.

Colonialism appears through the orientalist architecture projected into the Swiss context through the “pseudo-Japanese” building as a showcase of Suchard’s chocolate as a luxury product from distant lands, but also the polychromatic façade of the factory and its onion dome. The colonial patterns of the extractive activity in Sabana del Mar are more embedded in the oppressive relationship between the proprietors and the workforce. The study of the archival images shows the clear hierarchy between individuals through the subjects, how they posed for the pictures, the clothing they wear, and ultimately the captions added.