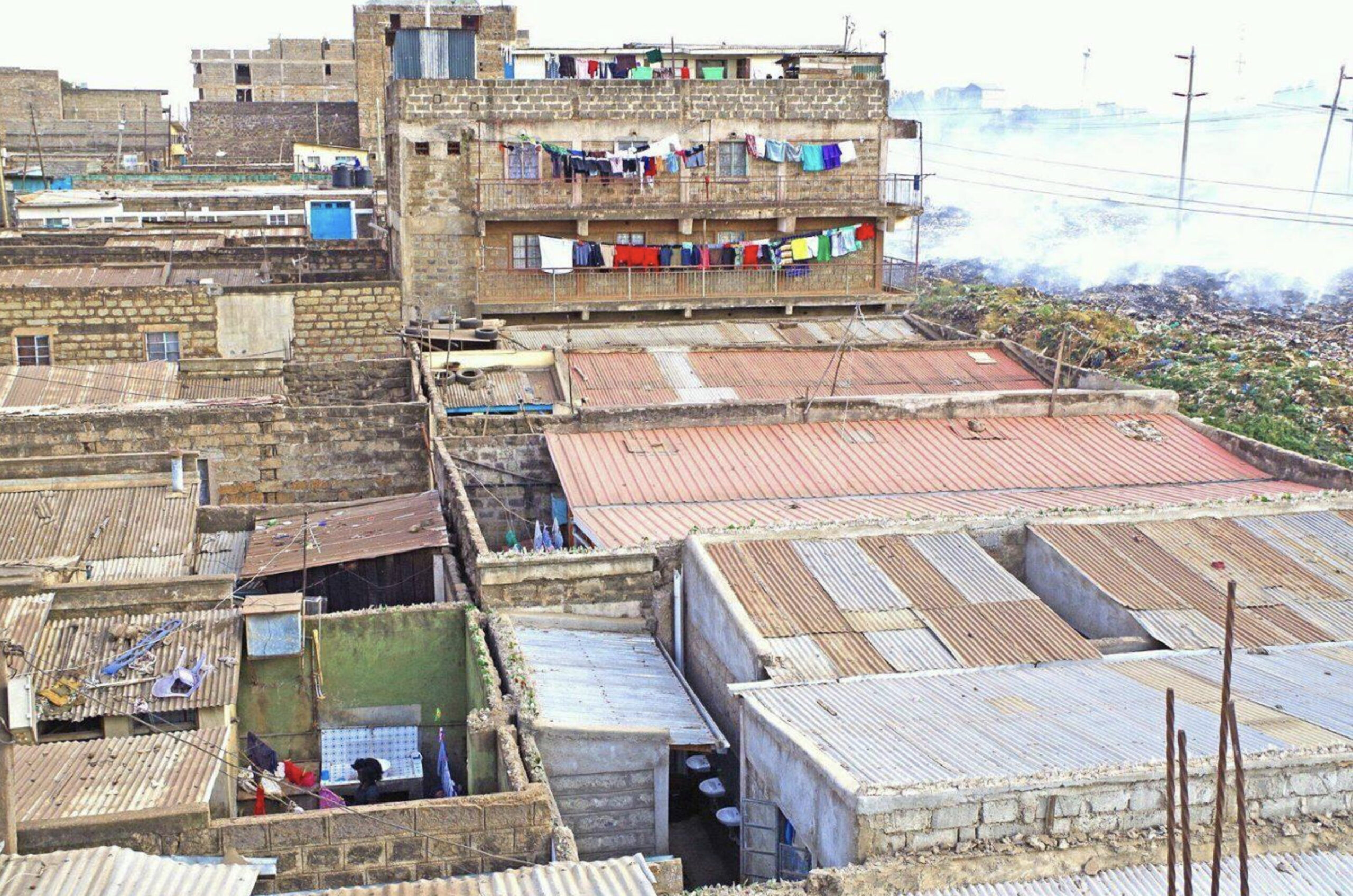

This housing strategy consisted of providing ‘sites’ – plots of land to construct dwellings on – in combination with a set of ‘services’, ranging from infrastructural features, such as sewerage and waste disposal, to market-based interventions that aimed to make cheap building material more easily accessible, and financial loan schemes that offered inhabitants the means to invest in their homes. For several decades from the 1970s, it was heavily endorsed by major actors such as the World Bank and the United Nations as a cost-efficient way to meet the most basic housing needs of a high number of people, whilst simultaneously offering authorities the means to direct the enormous growth of spontaneous settlements in the urban peripheries as part of their broader urban development plans. As such, these sites-and-services schemes have left a major imprint on many cities in the Global South. Despite this impact, however, their histories are not well documented.

This online exhibition is the outcome of our Autumn 2022 seminar course, ‘The City Lived’, in which students, beyond the praise and criticism directed at such projects, studied sites-and-services projects in the first place as material artefacts: as man- and woman-made built environments that have shaped the lives of thousands of people, whose history for that very reason deserves to be studied. They focused on 3 emblematic 1970–80s projects, in Ismailia, Soyapango, and Nairobi. After a general presentation of each project documenting how it came into being, each student explored a particular subtheme to analyze the project’s afterlife, ranging from material culture and social justice to the impact of road infrastructure.

- {{ item.label }} {{ item.address }}

The Dandora Community Development Project

Nairobi, Kenya

1975-1983

by Pierre Eichmeyer, Leandra Graf, Julia Tanner

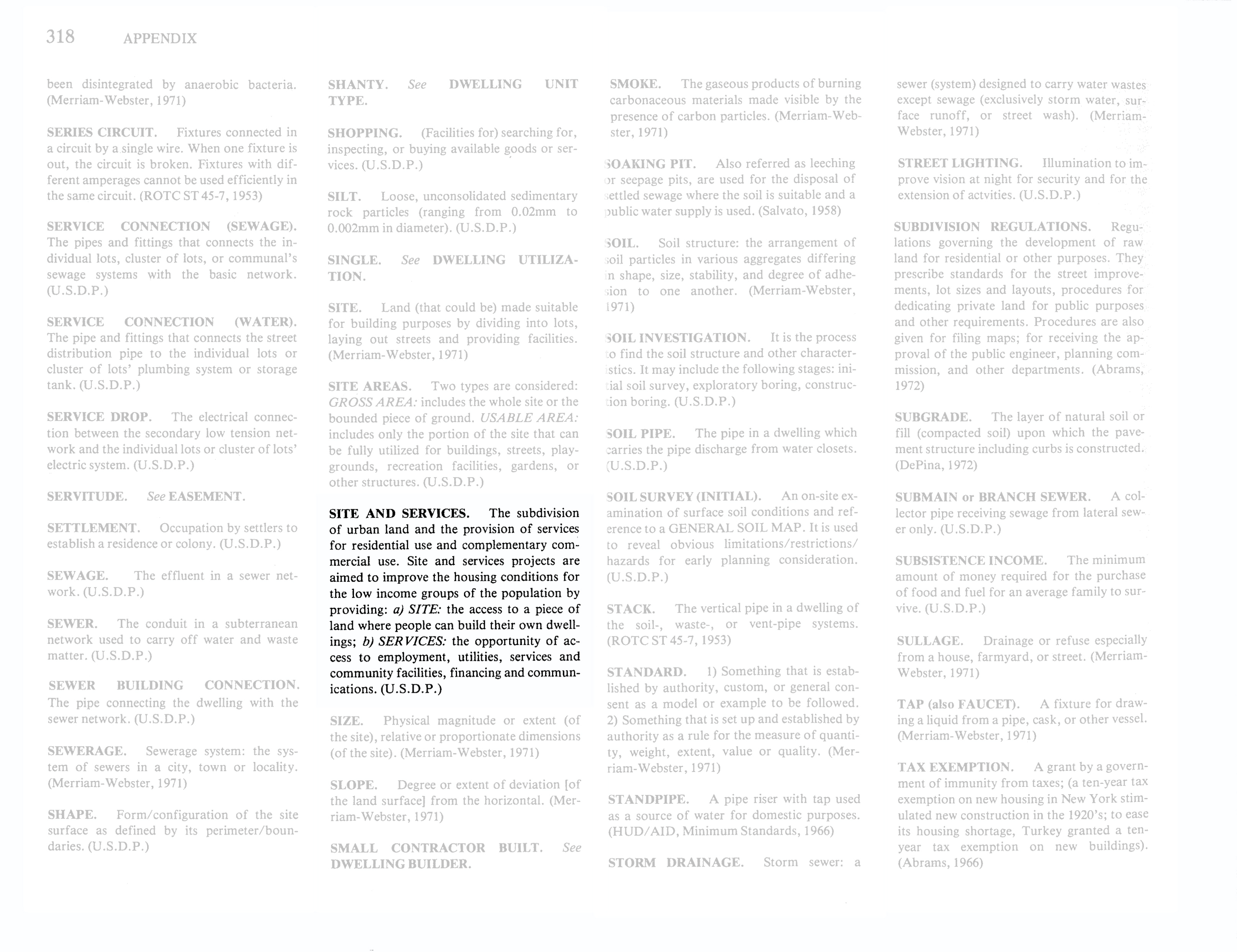

After the independence of Kenya in 1963, the city of Nairobi was still based on the inherited colonial spatial and racial segregation dating back to its first town plan in 1899. Postcolonial Nairobi was overwhelmed by the rapid influx of African immigrants. As a result, the city‘s boundaries were extended, and the number of new settlers multiplied. In 1973, the Nairobi Metropolitan Growth Strategy was an urban effort to confront the functional division of the city by proposing integrated, self-contained metropolitan neighborhoods. This strategy led to the birth of The Dandora Community Development Project – the first sites-and-services project in South-East Africa.

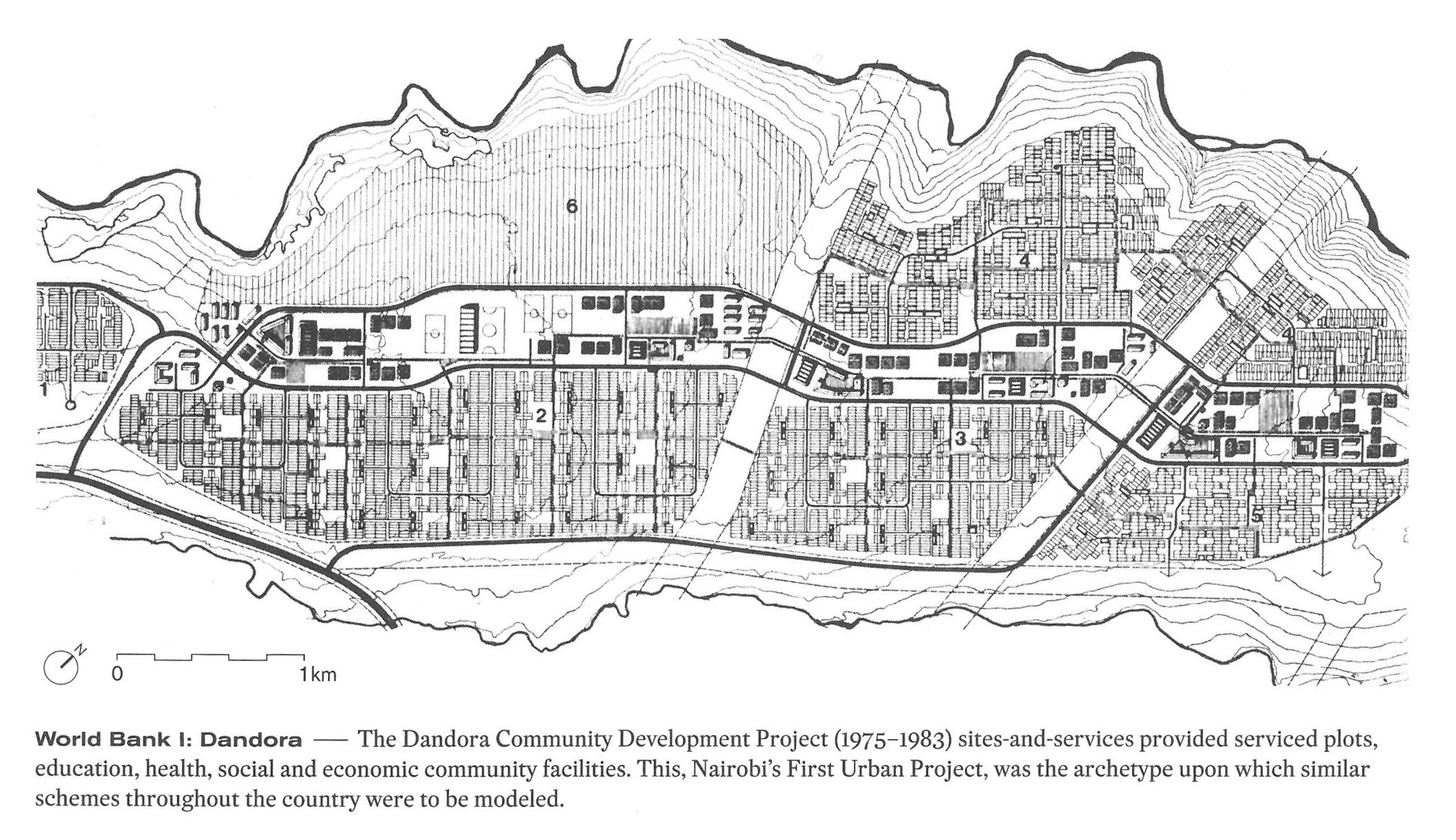

In collaboration with the World Bank and the UN, local government organizations initiated the large-scale development project. Because it was the first of its kind, it had an experimental approach and was meant to serve as a pioneering model that could – based on the results drawn from its execution – be adapted for future projects. However, lack of coordination and cooperation amongst various departments and committees and interference by council members and departments finally led to delays and cost increases. Nevertheless, after its completion, the project was generally viewed as a success.

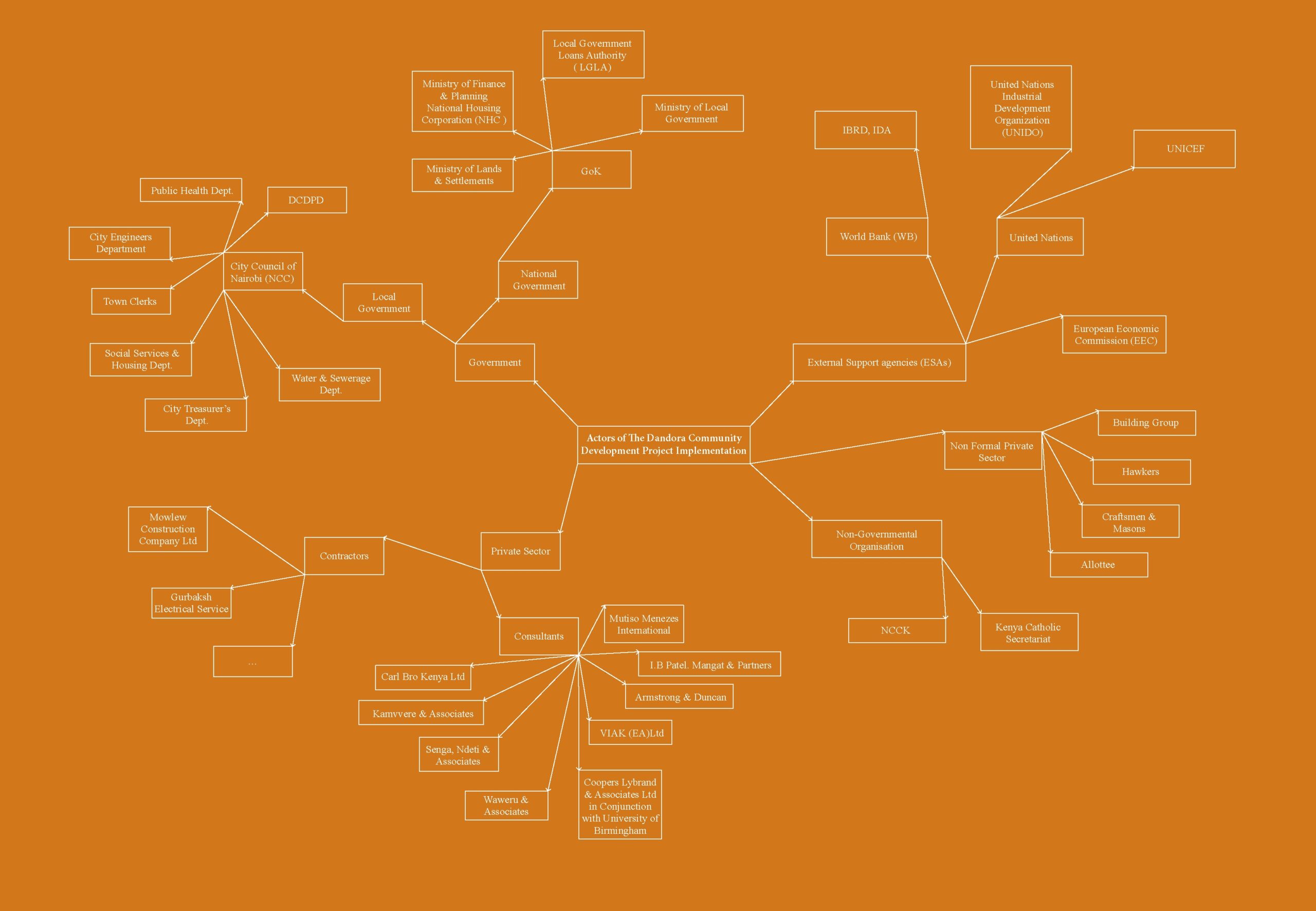

The site underwent many changes in the fifty years of the Dandora Community Development Project. While areas 1–5, as well as the central spine, were built in the 1970s and 1980s, the implementation of area 6 never took place. This area took on a life of its own and transformed into what we today know as the primary municipal solid waste dump for Nairobi. This has had a significant adverse effect on the health of the residents of Dandora and other neighboring communities. Dandora suffers from air pollution due to toxic waste spreading through the air and the burning of garbage, causing skin diseases, etc.

Furthermore, the lack of food forces people to search for nutrition at the dump site. Crime and unemployment rates are high, and many children have no access to education. On the other hand, the dumpsite creates many jobs, and even though its existence has a lot of harmful impacts, it cannot be removed without consequences.

Projects such as ‘Dandora Placemaking’, run by the Citilinks Africa Group in collaboration with local experts, community groups, academics, UN-Habitat, and NGOs, are working on strategies and models to upgrade Dandora. Its main goals are ‘(…) safe, inclusive and green public spaces for women, children and the elderly and the disabled’, as well as ‘creating safer and sustainable communities that provide opportunities for all’.1

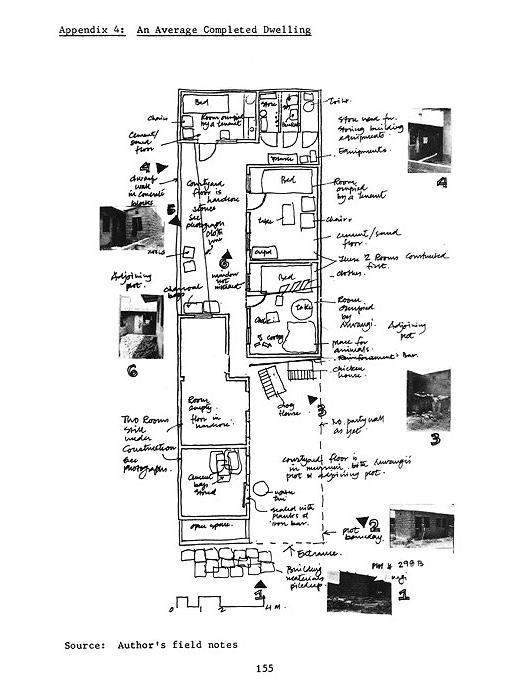

The Dandora Community Development Project site contains 6,000 plots with a density of 32 plots per hectare, each housing ten people. The biggest plots were built to subsidize the cheapest ones. Three options of wet core plots were available, in three different sizes and with a differing amount of already built rooms, from only the wet core up to 4 fully built rooms. Nowadays in most of the plots, the core kitchens have been transformed into rooms because of lack of space, the preference for private/outdoor cooking, and to earn more rent money for the owners. The wet core is still the main encounter point. Some plot boundaries have been modified, taking portions of neighboring plots: the residents thus provide themselves with a second room. In single-room houses, residents have incorporated soft partitions to divide the space. A micro-neighborhood feeling appears in a plot, as different tenants occupy each room. Their relationship impacts the quality and maintenance of the shared spaces.

Some neighborhoods organize themselves independently. A case study shows an example of a gated community in Dandora Phase 1. A self-financed and organized security system allows public access during the daytime while regulating access with guarded gates during nighttime. These communities appear repeatedly in Dandora – they are a solution for the wealthier inhabitants to increase their safety.

Cited Sources

1 Citilinks. “Dandora Placemaking.” www.citilinks-group.com/project/dandora-placemaking-making-cities/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Further Sources

1. ETH Studio Basel, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. Nairobi, Kenya – Migration Shaping the City. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers. 2014.

2. Lee-Smith, D. and P.A. Memon. “Institution Development for Delivery of Low-Income Housing. An Evaluation of The Dandora Community Development Project in Nairobi.” Third World Planning Review, vol. 10, no. 3. 1988.

3. Mbugua, Mungai Julius. Towards Improving Provision and Management of Road Infrastructure in Urban Site and Service Schemes: Case Study of Dandora – Nairobi. Nairobi: University of Nairobi. 2008.

4. “Dandora.” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dandora (last consulted 1.12.22).

5. Soni, Praful. On Self-Help in a Site and Services Project in Kenya. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1980.

6. Ivanovic, Glen Wash and Junko Tamura. “Core–housing and Collaborative Architecture: Learning from Dandora.” Proceedings ARCC 2015 Conference, Chicago.

Cover Image

Evolution of Typologies of the Urban Fabric of Dandora. Own work, based on plans from the texts cited above and photographs below.

Images

Cover Image: Evolution of Typologies of the Urban Fabric of Dandora. Source: Own work, based on plans from the texts cited above and photographs below.

Image I: Masterplan Dandora, by Mutiso Menezes International. Source: Mutiso Menezes International’s archives. From: Loeckx, André and Bruce Githua. “Sites-and-Services in Nairobi (1973-1987).” In Human Settlements. Formulations and (Re)Calibrations, ed. by Viviana d’Auria, Bruno De Meulder and Kelly Shannon. Amsterdam: SUN Academia. 2010.

Image II: Actors involved in The Dandora Community Development Project. Source: Own work.

Image III: Plots facing the dumpsite. Source: Facebook page of Dandora PHASE 4 Community, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/phase4community/

Image IV: An average completed dwelling, as documented by Praful Naran Soni. Source: Soni, Praful. On Self-Help in a Site and Services Project in Kenya. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1980.

Image V: Map of Gated Community. Source: Own work, based on: Ivanovic, Glen Wash and Junko Tamura. “Core–housing and Collaborative Architecture: Learning from Dandora.” Proceedings ARCC 2015 Conference, Chicago.

Informal Commercial Infrastructure

by Julia Tanner

In the original masterplan, formal markets and shopping facilities were planned in the central spine. Often, people ended up having to walk distances on insufficient streets to the next shop. The appearance of Informal Kiosks all over the residential areas can therefore be seen as a result of this situation. On his blog, one Dandora resident lists five different reasons why he and others shop at these local kiosks rather than the formal supermarkets or city stalls. Two overriding themes emerge from it: the need to support fellow residents, and the social exchange that takes place when shopping locally.

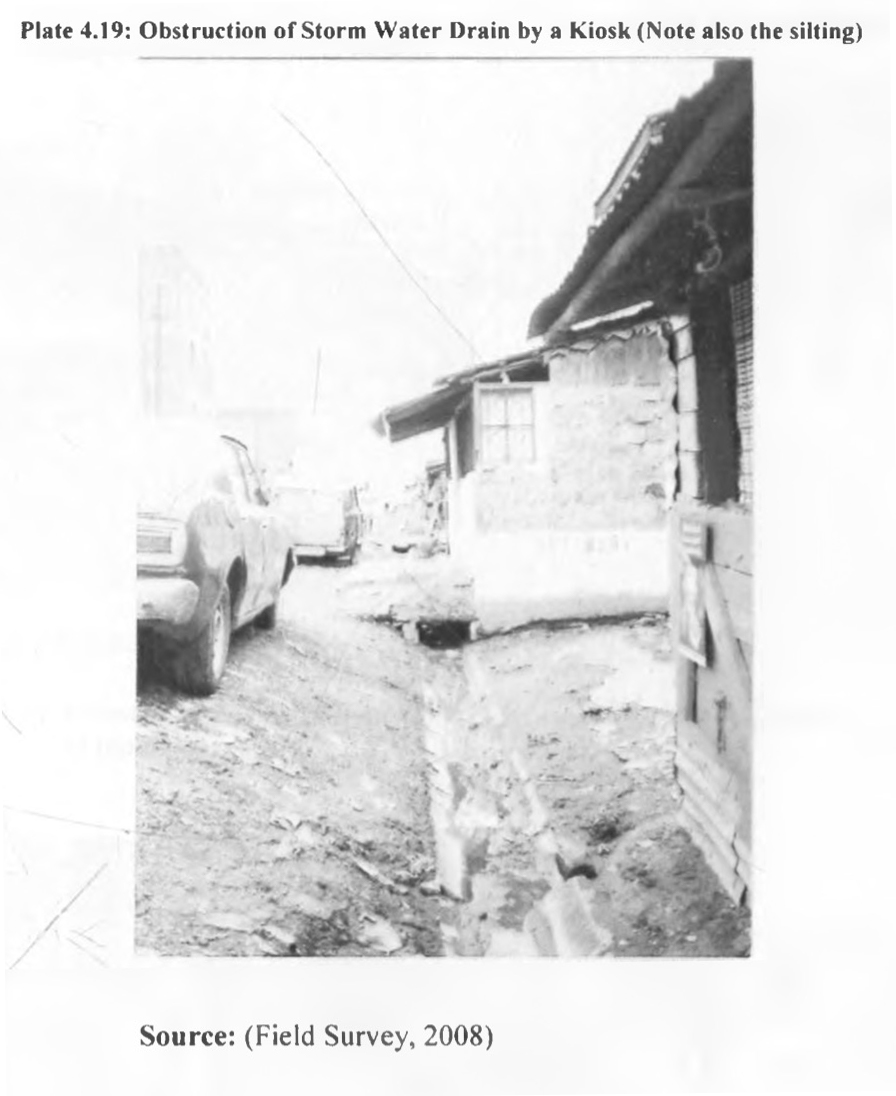

The construction of kiosks, which protrude onto the street as an extension of the properties, and often also as extensions of former temporary shelters, affects both the infrastructure and life on the street. When the kiosks were built, sometimes the water drainage was influenced, as well as the accessibility of the roads themselves. The influence is reciprocal, however, and so when roads are resurfaced, kiosks can get destroyed. The area manager ordered the destruction of several kiosks located on a road being renewed as recently as October 2022. This was followed by protests by various shopkeepers, most of them female. A so-called ‘Mama Mboga’, which literally means Mother Vegetable, is a female vegetable vendor in Swahili.

Many of the women of Dandora are rural immigrants who previously contributed to the family economy through farming and handicrafts. They traded in various goods, and with the resettlement to the cities, the women simply took on the role of procreation, household management, and raising children, while their husbands worked in factories to earn a living. Since it was very difficult for women to find jobs, they soon reconfigured their former role and adapted it to the new circumstances by becoming sellers of food or vegetables, and then again trading in various goods. This part of the informal economy remains an important mainstay today,as well as a platform for women to engage in the urban life of Dandora outside of their domestic sphere. With the construction of a kiosk, a woman not only breaks out of the boundaries of the property, but just as much out of the domestic sphere and the tasks that were initially assigned to her.

Sources

1. Anyamba, Tom. “Informal Urbanism in Nairobi.” Built Environment, vol. 37, no. 1. 2011.

2. Kinyanjui, Mary Njeri. Women and the Informal Economy in Urban Africa: From the Margins to the Centre. London: Zed Books. 2014.

3. Kiasman, Tony. “5 REASONS Why I Rarely Buy in Supermarkets, Shopping Malls and City Stalls.” Kiasman World, 29 Nov. 2016, kiasmanworld.blogspot.com/2016/11/5-reasons-why-i-rarely-buy-in.html. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

4. “Dandora Phase 5 estate traders stage protest.” YouTube, uploaded by KBC Channel 1, 24 Oct. 2022, www.youtube.com/watchv=ff8hiHnOZ28&ab_channel=KBCChannel1.

Cover Image

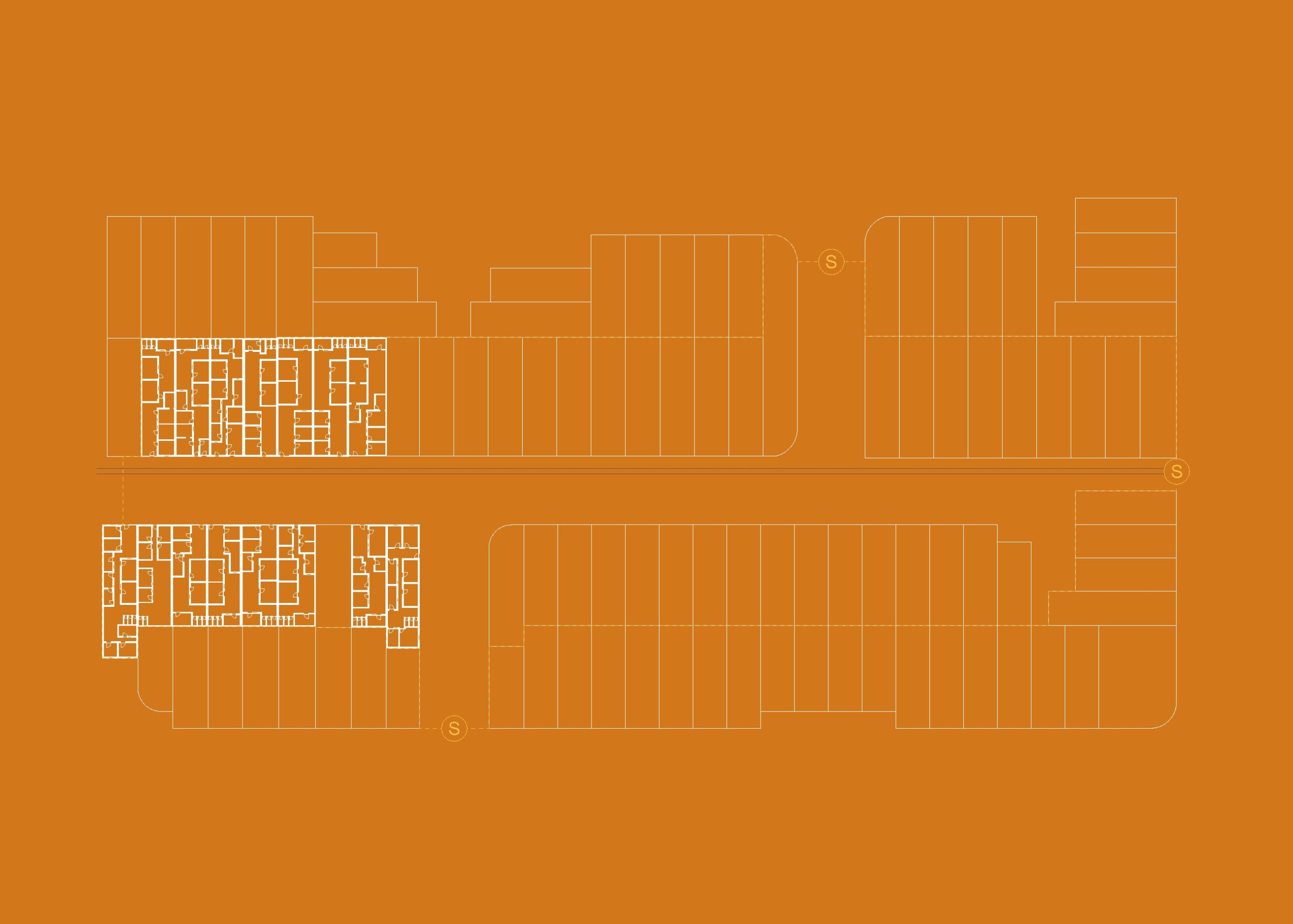

Informal Commercial Infrastructure. Source: Own work, based on the common drawing.

Dandora at Night

by Leandra Graf

What happens in Dandora at night?

Nairobi – a vibrant megacity in East Africa, a bright spot on Earth at night when seen from space. In the eastern part of it, Dandora – a poor neighborhood equipped with only basic infrastructure. The road and water system is reduced to a minimum, and the electrical and lighting provision is scarce.

When Dandora was built in the 1980s, the lighting infrastructure was drawn up, but was not the main focus. In 2005 it was observed that ‘Street lights where existing were either not functional, damaged, or dirty (…) in most of the areas. Obstruction by informal business (kiosks) was also noted’.1 In a survey conducted in 2008, it was noted that ‘On a priority basis, the respondents desired improved street lighting (35.9 per cent), followed closely by repairing of roads (33.7 per cent) (…)’.2

Today, high-mast lighting (up to 40m high) hovers above the inhabitants. Along the main traffic axes, the lights shine 360 degrees. The most common typology is high-mast lighting, with four spots that glow in four directions. Furthermore, there are street lamps with only single spots, and, occasionally, the inhabitants mount lights onto the entrances of their houses or businesses. It is noted that on big roads, lighting provision is generally given, in contrast to the more dense and self-built urban fabric where the provision is scarce.

The inadequate presence or, rather, absence of lighting provision creates two opposite schemes of how people move around the neighborhood: day and night. While people move around relatively freely by daylight, after dark, the lack of public lighting infrastructure makes it difficult even to access shared essential services and hinders residents from feeling safe outside. The area’s history of darkness is not only associated with insecurity, but also strongly associated with criminality.

Several projects address the lack of lighting in informal settlements. One example is the bottom-up approach with LED lights, as was the case in Khayelitsha, Cape Town.3 Another is the top-down approach of ‘Adopt a light’,4 which has already upgraded several poor neighborhoods in Nairobi. Can they serve as a long-term solution for upgrading the Dandora neighborhood?

Cited Sources

1. Mbugua, Mungai Julius. Towards Improving Provision and Management of Road Infrastructure in Urban Site and Service Schemes: Case Study of Dandora – Nairobi. Nairobi: University of Nairobi. 2008.

2. Ibid.

3. Briers, Stephanie. “The Violence of Lighting in Khayelitsha.” The Architectural Review. September 2021.

4. Adopt a Light. http://www.adopt-a-light.com/slum_lighting.php. Accessed 18 Nov. 2022.

Further Sources

1. Lee-Smith, D. and P.A. Memon. “Institution Development for Delivery of Low-Income Housing. An Evaluation of The Dandora Community Development Project in Nairobi.” Third World Planning Review, vol. 10, no. 3. 1988.

2. “End of the Road for Dandora’s Most Dangerous Gangster as Detectives Shoot Him Dead after a Fierce Gun Battle.” The Kenyan Daily Post. 16 August 2021. https://kenyan-post.com/2021/08/end-of-the-road-for-dandoras-most-dangerous-gangster-as-detectives-shoot-him-dead-after-a-fierce-gun-battle-it-was-like-a-movie-read/. Accessed 18 Nov. 2022.

3. Thornhill, Ted. “The Brutal Reality of Life on Nairobi’s Streets.” MailOnline. 25 November 2015. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3333692/The-brutal-reality-life-Nairobi-s-streets-pictures-reveal-hardships-Kenya-s-capital-gun-crime-rife-young-girls-forced-turn-prostitution.html. Accessed 18 Nov. 2022.

Cover Image

High-Mast Lighting with four Spotlights. Source: Own work, based on the common drawing.

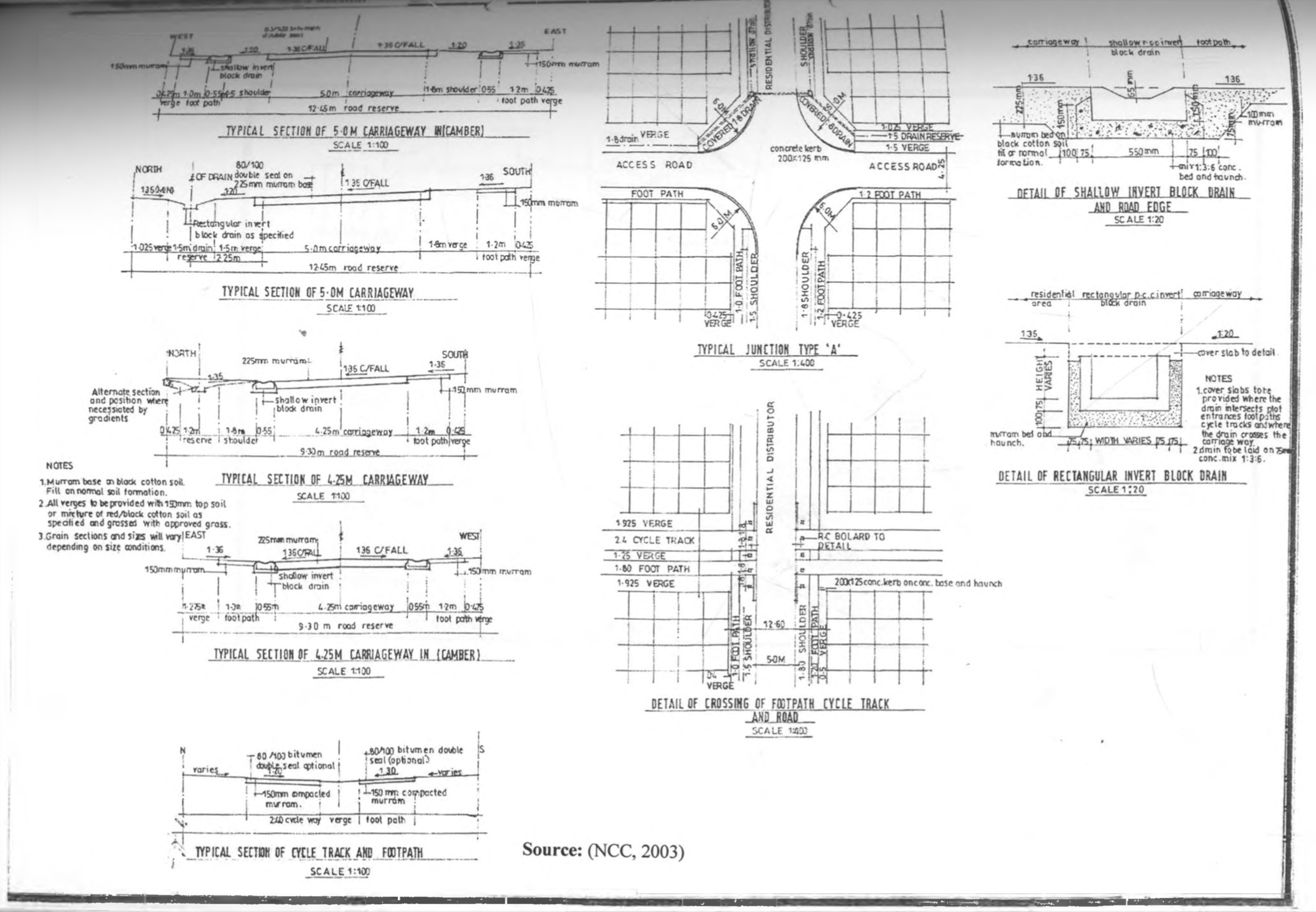

Roads in Dandora

by Pierre Eichmeyer

The situation of the road infrastructure

A 2008 case study from the University of Nairobi shows that despite the good planning and organizing of the road infrastructure and network, most of the access roads are nowadays highly dilapidated. Several problems were observed, such as the presence of potholes, cracking, and other damage, but also obstructions from kiosks, soil heaps, and construction debris, as well as vegetation. These elements show a lack of maintenance and cleanliness by the city council. In some areas, residential buildings and commercial kiosks have encroached on the footpaths and made them inaccessible. This impacted the security of the pedestrians, forcing them to walk on the street and increasing the accident rate.

The lack of safe spaces can limit access to schools, health services, commercial places, and leisure activities, and has a direct impact on the wealth, education, and health of the inhabitants. In fact, plot owners are charged a certain amount of money monthly for road maintenance in the estate. This, and all the problems listed above, repeatedly led to big demonstrations and road blockages by residents hoping to get the attention of the government and the city.

Several ways of dealing with the problems

The Kenyan Government started a plan of infrastructural upgrading in several areas of the city, including Dandora, to improve the accessibility to essential goods and services, mainly because of the health situation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The plan includes upgrading all the targeted roads to bitumen standards. However, this only concerns the main traffic roads of Dandora, and not the side streets leading to the dwellings.

A second project funded by UN-Habitat and the Dutch Doen Foundation has been implemented since 2018 by the Dandora Transformation League. It deals with these residential side streets, and has already been tested on a Model Street, with new paving, painted walls, children’s play areas, and planting of trees. The goal is to change Dandora’s reputation for high crime and pollution and make it an attractive district.

Residents shared their opinion on the project. They all felt a big transformation of their affection to the neighborhood. Besides better safety for pedestrians and children, businesses can open much longer. Also, women feel significantly less segregated and anonymous as they can go out on the streets without the fear of getting robbed. The maintenance of the cleanliness and safety of the road also created new employment for residents, promoting foot-traffic. ‘There has been a boost to the communal identity with the introduction of the court systems. The neighborhoods have been divided into courts, each having their own independent gate with their name and color. This makes it easier to organize communal activities (…) (and) has led to a thriving community’, said one inhabitant.1

In conclusion, small interventions involving the residents directly and making them participate in the design and construction increases the safety and cleanliness of the road, but also strengthens the communal feeling of the neighborhood.

Cited Sources

1. “‘Model Street’ – Making Cities Together: Resident Stories.” World Habitat Awards, 2018.

2. https://world-habitat.org/world-habitat-awards/winners-and-finalists/making-cities-together/#resident-stories.

Further Sources

1. Mbugua, Mungai Julius. Towards Improving Provision and Management of Road Infrastructure in Urban Site and Service Schemes: Case Study of Dandora – Nairobi. Nairobi: University of Nairobi. 2008.

2. Bacha, Derrick. “Githurai Residents, Motorists Lament over Poor State of Key Road.” Nairobi News, 17 March 2021. https://nairobinews.nation.africa/githurai-residents-motorists-lament-over-poor-state-of-key-road/.

Cover Image

Evolution of the Road Infrastructure of Dandora. Source: Own work, based on the common drawing.

Colonia El Pepeto

Soyapango,

El Salvador

1974-1975

by Victor Kleyr, Amélie Lambert, Lars Ludes, Shreya Sen

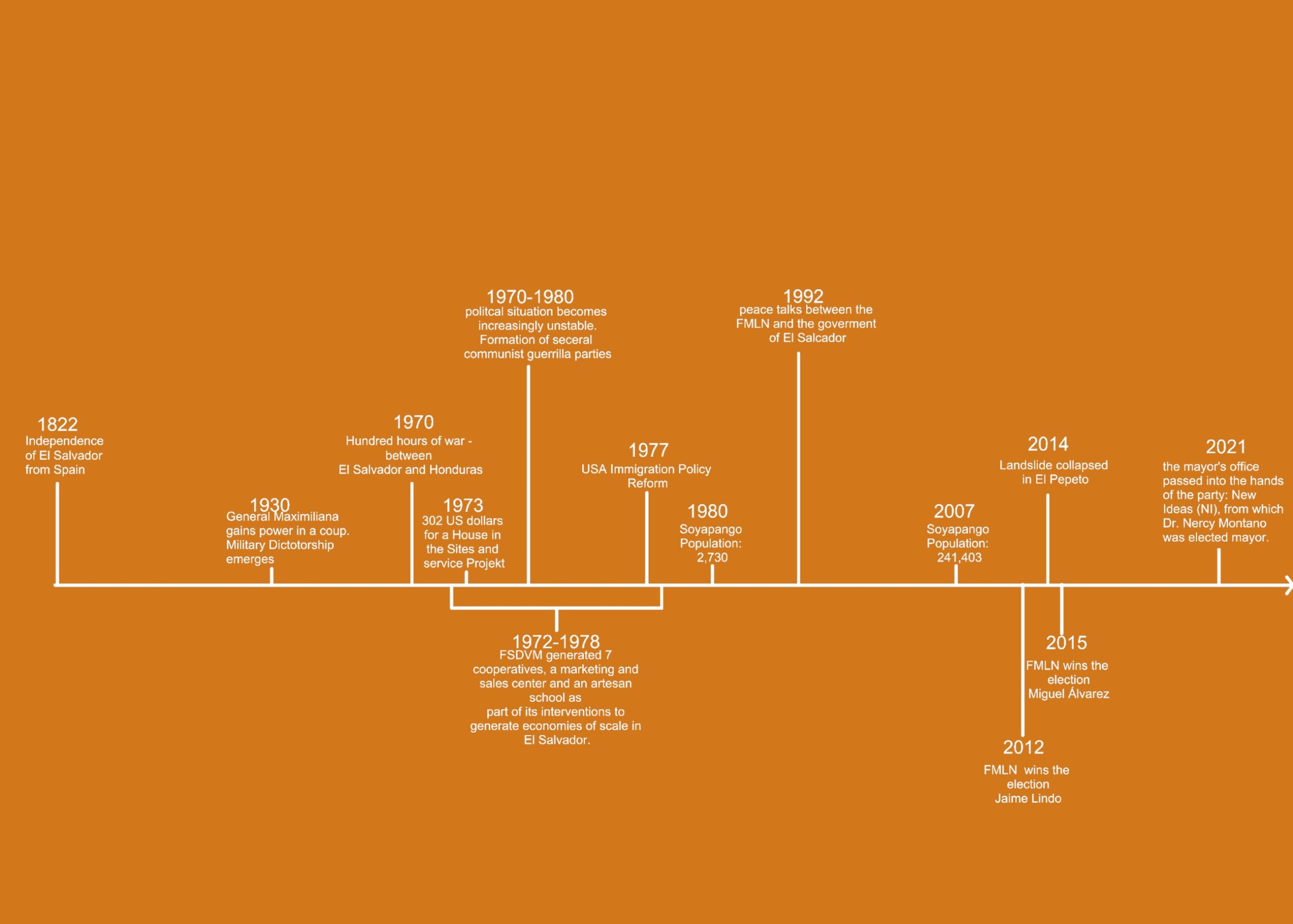

El Salvador is the smallest but most densely populated Central American country.1 After gaining independence in 1839, the new coffee production encouraged the economic development of the country, but also lead to rural exodus and social inequalities.2 At the dawn of the 1970s, the Hundred Hours’ War – which forced the return of around 100,000 Salvadoran emigrants3 – and guerillas instilled a climate of instability, while the country still suffered from social inequities and poverty.

In this context, the Soyapango sites-and-services project was part of a wider program which tried at that time to address the lack of housing solutions: a major part of the urban population lived in unauthorized or overcrowded dwellings.4 It served as pilot project within a five-year plan that was set up to balance the situation in about nine sites, targeting mainly households earning less than 100 USD per month.5

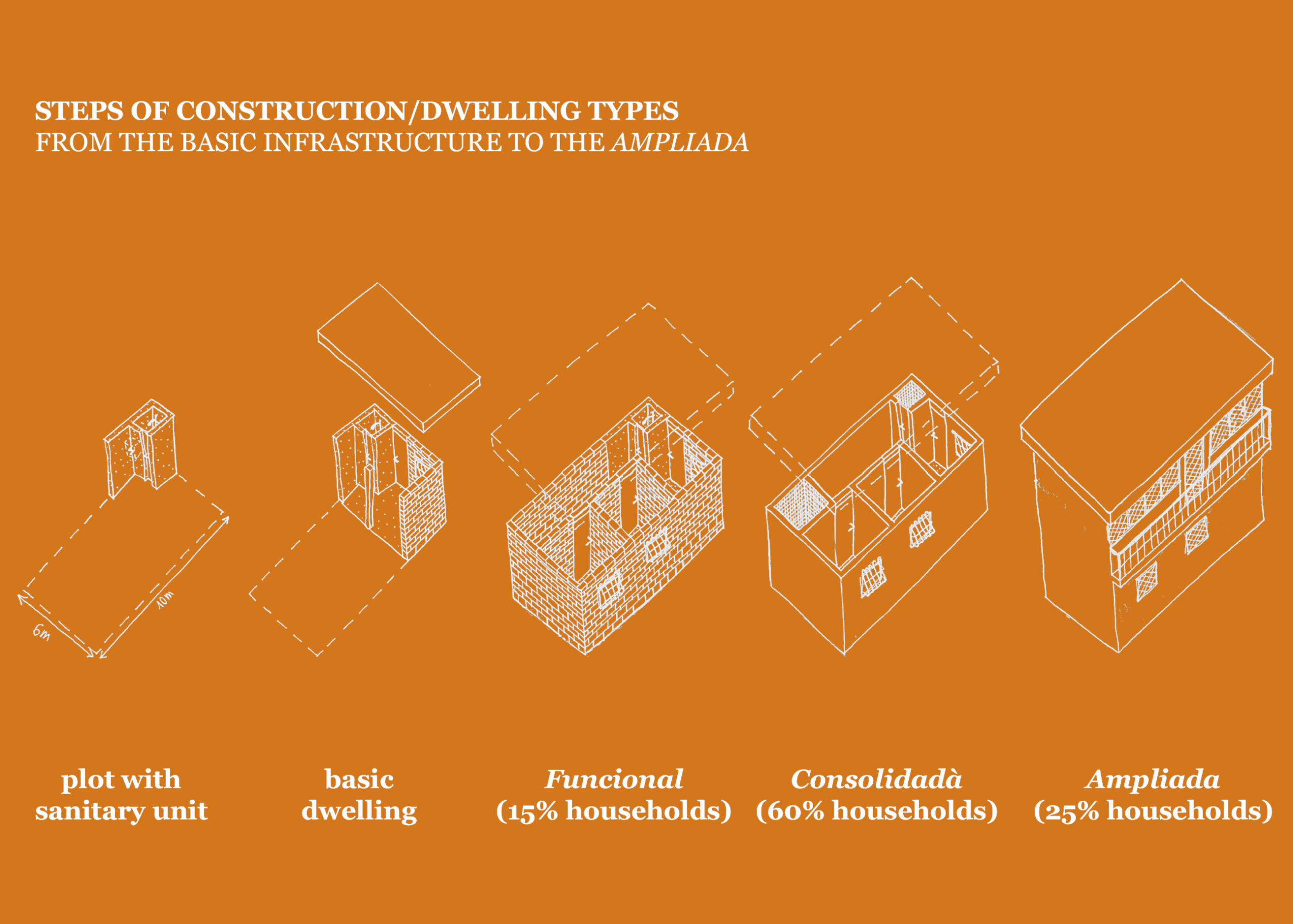

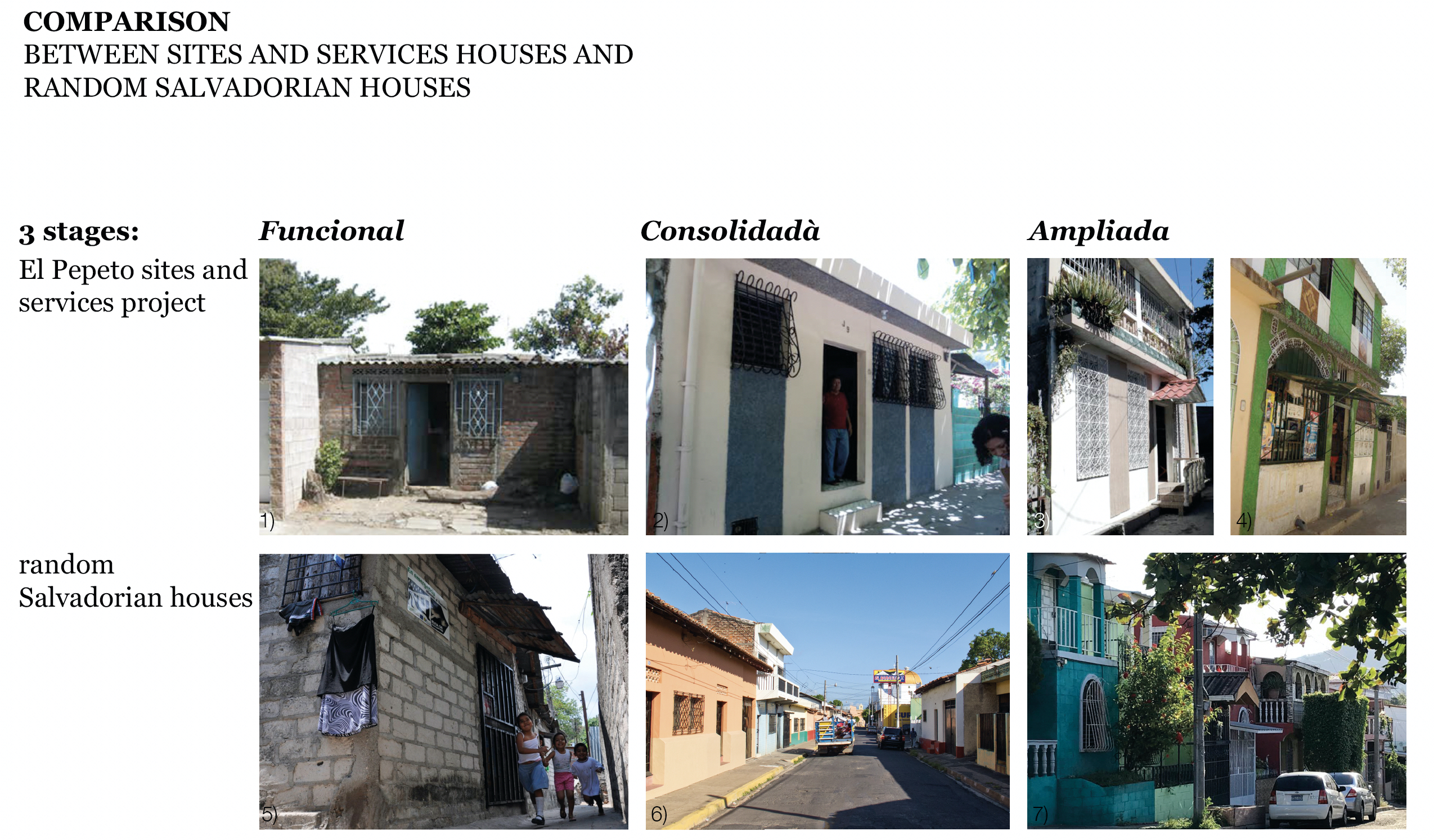

With an area of 6 km², the project provides homes and facilities for 530 families on land bought from the Salvadorean Air Force.6 It continues the punctual expansion of Soyapango toward the countryside, and is today commonly known as the Colonia El Pepeto neighborhood. The plots mainly measure 6 by 10 meters and the dwelling usually covers the whole plot. They are serviced with basic infrastructure of water, sewerage, and optional electricity connections. They have an enclosed sanitary unit which is the first grade of construction. Half of the lots were directly provided with the second grade, a basic dwelling consisting of an asbestos cement roof, a wooden openings frame, and a concrete structure.7 Built in stages, the project was pragmatic and affordable for the targeted population (302 USD / house in 1973, eq. 2,000 USD in 2022).8

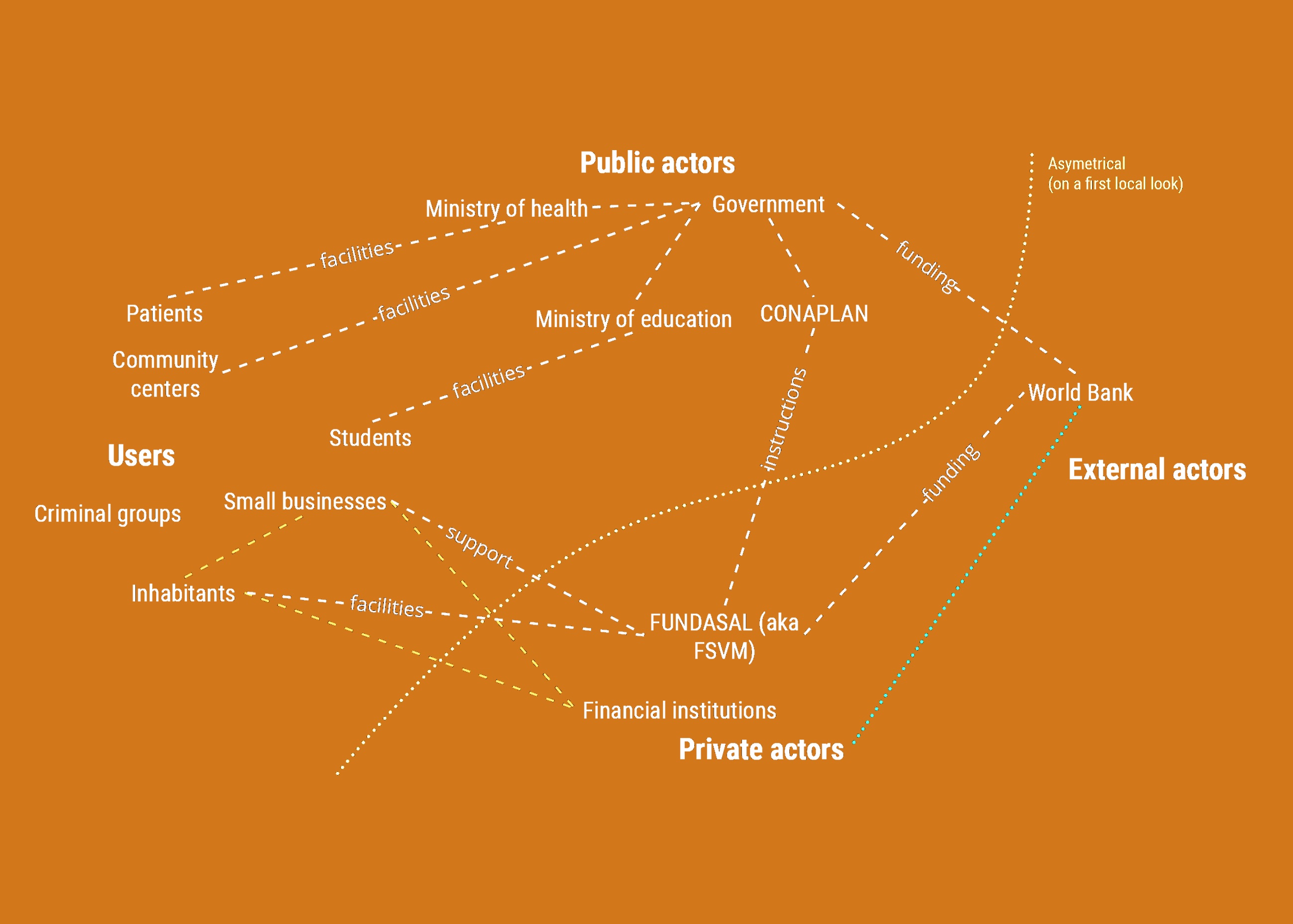

The main actors of this project are the Salvadorean government, the World Bank, the FSDVM (Salvadorean Foundation for Development and Low-Cost Housing).9 They are, respectively, the ‘representatives’ of the public, external, and private actors, to which we add the group of the users. Mapping the relationships between these groups shows a strong asymmetry between the users/public actors and the private/external actors regarding responsibility relative to number. It is intriguing to compare this to the project’s interests, which, despite being firstly a response to the lack of dwelling in the country’s cities, seem to be highly motivated by financial reasons through the role of private/external actors.

The FSDVM saw the introduction of housing solutions as a way to act for social change: the project would allow the paradigm of urban housing in El Salvador to be changed on an institutional and legitimatized level, offering homes for a large number of people and a platform for community development.10 The Foundation even supported the project’s building phase with a mutual help program where members of the future households and communities would take part directly on the worksite, taking care of tasks which did not require specialized building knowledge.11

The sites-and-services project, originally surrounded only by sugar cane fields and the airport, has expanded around the site. The previously unpaved access road has developed into a system integrated into the city’s road network. Sports fields and schools are used for cultural events such as dance and music.12 In 2014, a landslide damaged the units, which were supposed to be landslide-proof,13 and many members were forced to continue living in their accommodation despite the invidious circumstances,14 questioning the maintenance of the project since its settlement 40 years before.

Sources

1. “Salvador.” Wikipedia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salvador (last consulted 20.11.22).

2. “Histoire du Salvador.” Wikipedia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histoire_du_Salvador (last consulted 11.10.22).

3. Rouquié, Alain. “Honduras-El Salvador. La guerre de cent heures: un cas de ‘désintégration’ régionale.” Revue française de science politique, vol. 21, no. 6. 1971. pp. 1290-1316.

4. World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

5. Ibid.

6. Gattoni, George, Reinhard Goethert and Roberto Chavez. El Salvador: Self-Help and Incremental Housing: Likely Directions for Future Policy. IDB, 15 Oct. 2011.

7. Ibid.

8. Price equivalent calculated via https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/.

9. World Bank. El Salvador. Op. cit.

10. Harth, Alberto and Silva Mauricio. “Mutual Help and Progressive Development Housing. For What Purpose? Notes on the Salvadorean Experience.” In Self-Help Housing: A Critique, ed. by Peter Ward. London: Mansell. 1982. Ch. 9.

11. World Bank. El Salvador. Op. cit.

12. “Fiesta navideña, Col. El Pepeto, Soyapango.” Facebook, uploaded by Efraín Guatemala, 9 Dec. 2020, https://www.facebook.com/efrainguatemalaNI/videos/404350114222026/

13. World Bank. El Salvador. Op. cit.

14. Noticias4VisionTCS, news channel. El Pepeto 3 fue catalogado “Peligros” por Protección Civil (16/06/2014). YouTube, uploaded by Noticias4VisionTCS, 17 Jun. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPICuTEBTTk

Cover Image

Comparison of layout site of Soyapango the planned Sites-and-Services project in 1974 vs tody. Source: Own work, based on: World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

Cover Image:

Comparison of layout site of Soyapango the planned Sites-and-Services project in 1974 vs today. Source: Own work, based on: World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

Images:

Image I: Actor network. Source: Own work (Victor), based on: World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

Image II: Steps of construction and dwelling types – from basic construction to the Ampliada. Source: Own work (Amélie), based on: Gattoni, George, Reinhard Goethert and Roberto Chavez. El Salvador: Self-Help and Incremental Housing: Likely Directions for Future Policy. IDB, 15 Oct. 2011.

Image III: Timeline. Source: Own work (Lars), based on: “Salvador.” Wikipedia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salvador (last consulted 20.11.22); “Histoire du Salvador.” Wikipedia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Histoire_du_Salvador (last consulted 11.10.22); Rouquié, Alain. “Honduras-El Salvador. La guerre de cent heures: un cas de ‘désintégration’ régionale.” Revue française de science politique, vol. 21, no. 6. 1971. pp. 1290-1316; Murphy, Matt. “El Salvador: Thousands of Troops Surround City in Gang Crackdown.” BBC News, BBC, 4 Dec. 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-

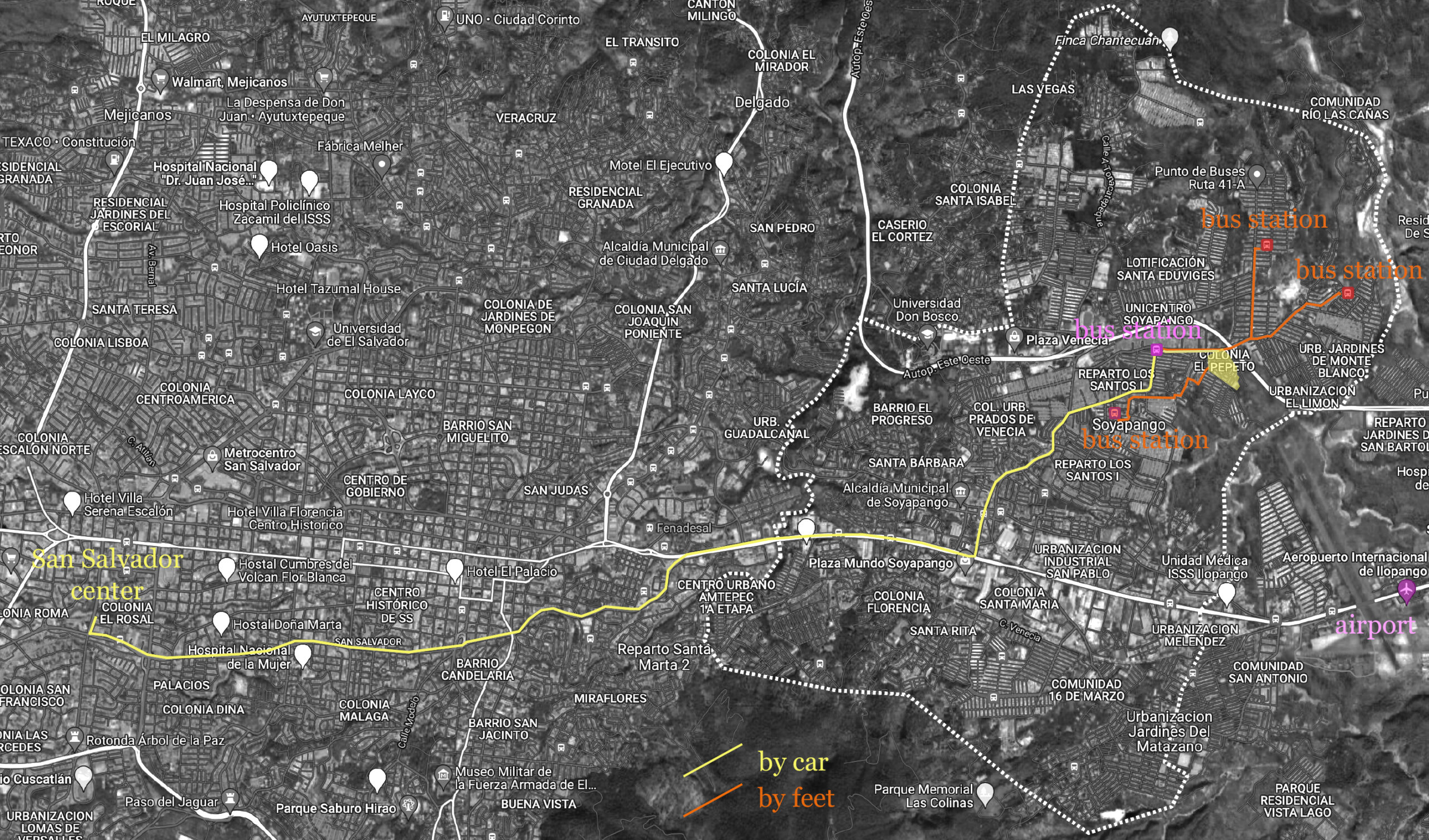

Image IV: Urban context. Source: Own work (Amélie), based on Google Earth.

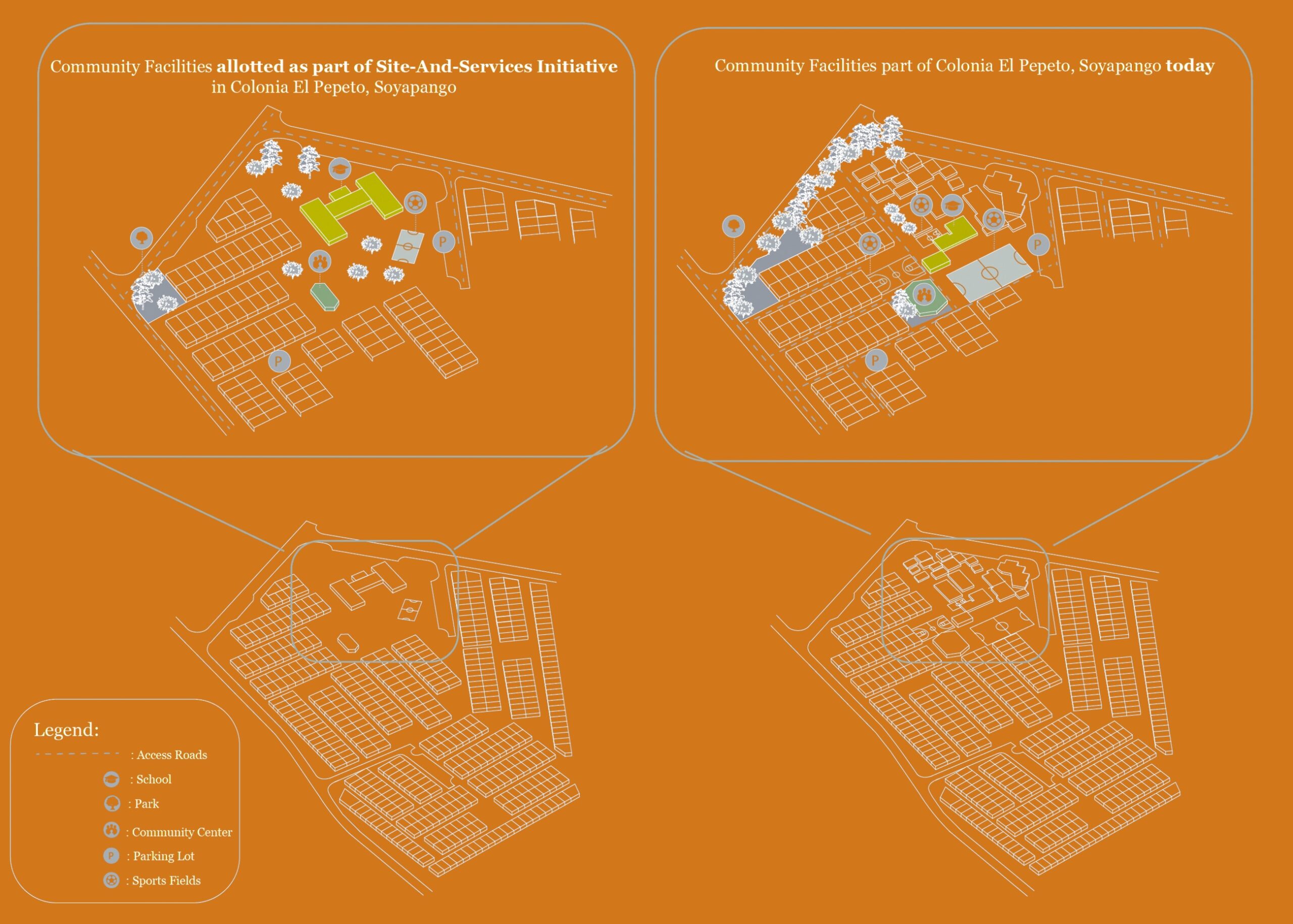

Image V: Community facilities allotted as part of the project vs facilities today. Source: Own work, based on: World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

External Actors’ Influence

by Victor Kleyr

Looking at the project beyond its local/national scale, we can question how actors from abroad are partly shaping the evolving spatial and social conditions of the project. By deconstructing the roles of institutions such as the World Bank or strong western nations such as the United States or Germany, which hold a major part of the responsibilities and overall control of the project, we discover a lot of underlying mechanisms.

At first glance, these external actors seem to be far away from the actual spatial condition of the households, but their influence, often immaterial, translates into several spatial phenomena, which allows us to understand the polarized role of those external actors at a core unit scale. The World Bank financed 100% of the costs related to the infrastructures and core unit construction, granting it a certain degree of control on those crucial part of the dwellings: the standard and ways of processing could be decided by the institution.1

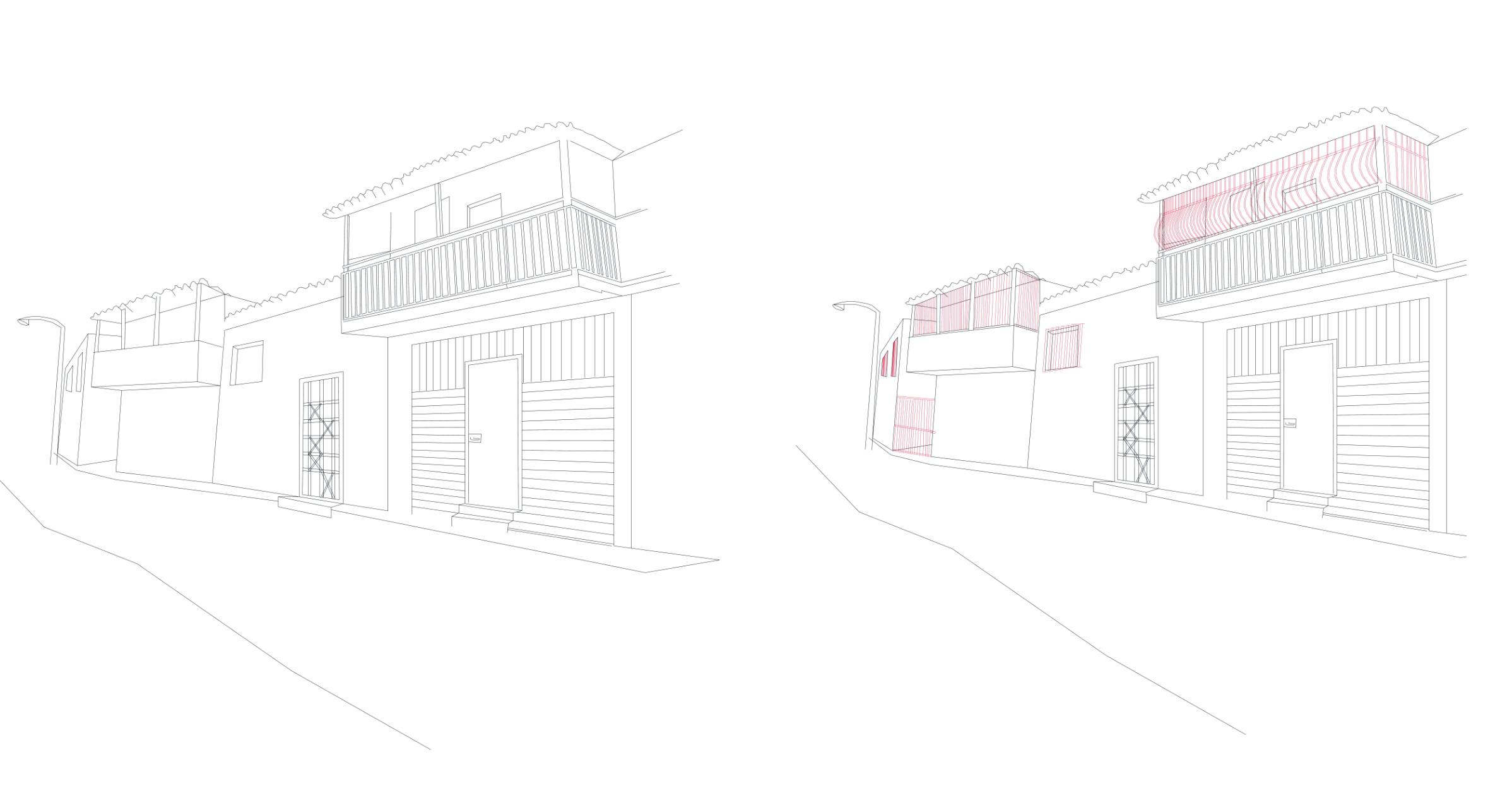

The same institution championed the importance of the private actors in the project, talking about ‘a useful example to other countries facing similar shelter problems.’2 This appraisal of privatization has existed, then, since the birth of the project, but its translation over time from the financial sphere to the built environment is confirmed when you take a look at the support of a country like Germany: via different governmental institutions (KfW and GTZ), throughout the 1990s and the 2000s the western state funded different private financial actors of the area, most structured around micro-credit.3 This format of loans was in a range corresponding to the extensions of the dwellings planned by the project, or unexpected floor additions. The multiple architectural faces presented today by the originally identical units can therefore be partly attributed by the motivation of the external actors for a private market, and not governmental support to the people for housing extensions.

The way the project was drawn and imagined in the 1974 documents also reveals a lot about the spatial and constructive projection of the World Bank: the units are represented through a typical western household model of a couple and two children, a lifestyle and a demographic directly imported from the frame where the project was planned. The cultural role of these first external financial supports in the El Salvador postcolonial context can therefore be questioned.4

Sources:

1. World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

2. Ibid.

3. Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. “El Salvador: An Organization called FUNDASAL (Foundation for Salvadorean Development and Affordable Housing), Its History, Organization, Goals, Political Affiliations, Funding (Particularly Funding by the German Government); Reports of Employees Being Threatened or Harassed; Allegations of Corruption or Fraud by Employees (1998-1999).” 28 February 2001. https://www.refworld.org/docid/3df4beaa1c.html https://www.refworld.org/docid/3df4beaa1c.html.

4. World Bank. El Salvador. Op. cit.

Cover Image:

Actors’ network scheme highlighting the role of external actors. Source: Own work, based on sources cited in text.

Appropriation of Private Space

by Amélie Lambert

It is interesting to observe how private space was appropriated by the residents of Colonia El Pepeto by analyzing the recurring and contrasting patterns, while keeping in mind that the project was in part an incremental self-help process.

The sanitary unit was built by mutual help for every plot. This gave access to water (WC, shower, wash basin) and sewerage to each family. By comparison, we know that in the 1970s, only 40% of houses benefited from water supply and sewerage in El Salvador.1 This bad sanitation encouraged the proliferation of gastro-intestinal diseases, which were one of the main causes of death in the country.2 Therefore, the easy access to these services was seen as a great opportunity. Half of the plots were already provided with a basic dwelling, so were more expensive, but often chosen by the lowest income families such as unmarried women with children or elderly persons who couldn’t undertake construction. Families with higher income often chose less complete units, in order to then invest more in designing them how they wanted.3

This gave a good start for the next steps that were made by self-help. The occupants benefited from a (local) construction material credit to build a habitable house, adapted to their needs and incomes. We can differentiate three types of finished dwellings. The Funcional house required the least amount of investment. Families just added a room or more and, interestingly, window bars. We understand that security is a priority for Salvadorians because of gang activity.4 Most people opted for the Consolidadà house; they expanded the rooms and amenities, and resorted to aesthetic changes, like painting the facades. Finally, a third group built second and sometimes third stories, and upgraded services such as the kitchen; this is known as the Ampliada type.

Most families live in a Consolidadà or an Ampliada house, even though more than half are considered as low-income households. This will for investment can be explained by the great benefits that the occupants can expect from the project. The most important benefit is the security of owning the land, and not taking the risk of being evicted – something that a lot had experienced before, living in an illegal settlement because of the housing deficit in El Salvador.5 For most, this is their first opportunity to have a legal status. In addition, many families previously shared their house with other families. Here, they have the possibility to possess their own space, and hence to appropriate it more easily. Furthermore, hygiene is considerably improved.

Another appealing element is the great programming of community facilities by the FSDVM, which were also built by mutual-help – this generated, with the building of houses, a great source of employment and income, and also a strong feeling of community and solidarity.6

Evidence for the great appropriation of the sites-and-services project by the Colonia El Pepeto residents is the resemblance of their houses to any typical slum or private project, whose appearance is totally controlled by the owners. Thus, we can deduce that they had the necessary resources to design their houses how they wanted.

Sources

1. International Bank. Report and Recommendation of the President to the Executive Directors on a Proposed Loan and Credit to the Republic of El Salvador for a Sites and Services Project. October 15, 1974.

2. Bamberger, Michael. EI Salvador: A Country Profile, May 1980.

3. World Bank. El Salvador: Second Urban Development Project, April 4, 1977.

4. Gattoni, George, Reinhard Goethert and Roberto Chavez. El Salvador: Self-Help and Incremental Housing: Likely Directions for Future Policy. IDB, 15 Oct. 2011.

5. Ibid.

6. Bamberger, Michael. The First EI Salvador Sites and Services Project: Summary of the Main Findings of a Five-Year Evaluation, July-October 1981.

Cover Image

Comparison of layout site of Soyapango the planned Sites-and-Services project in 1974 vs today. Source: Own work, based on: World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

The Influence of Gangs

by Lars Ludes

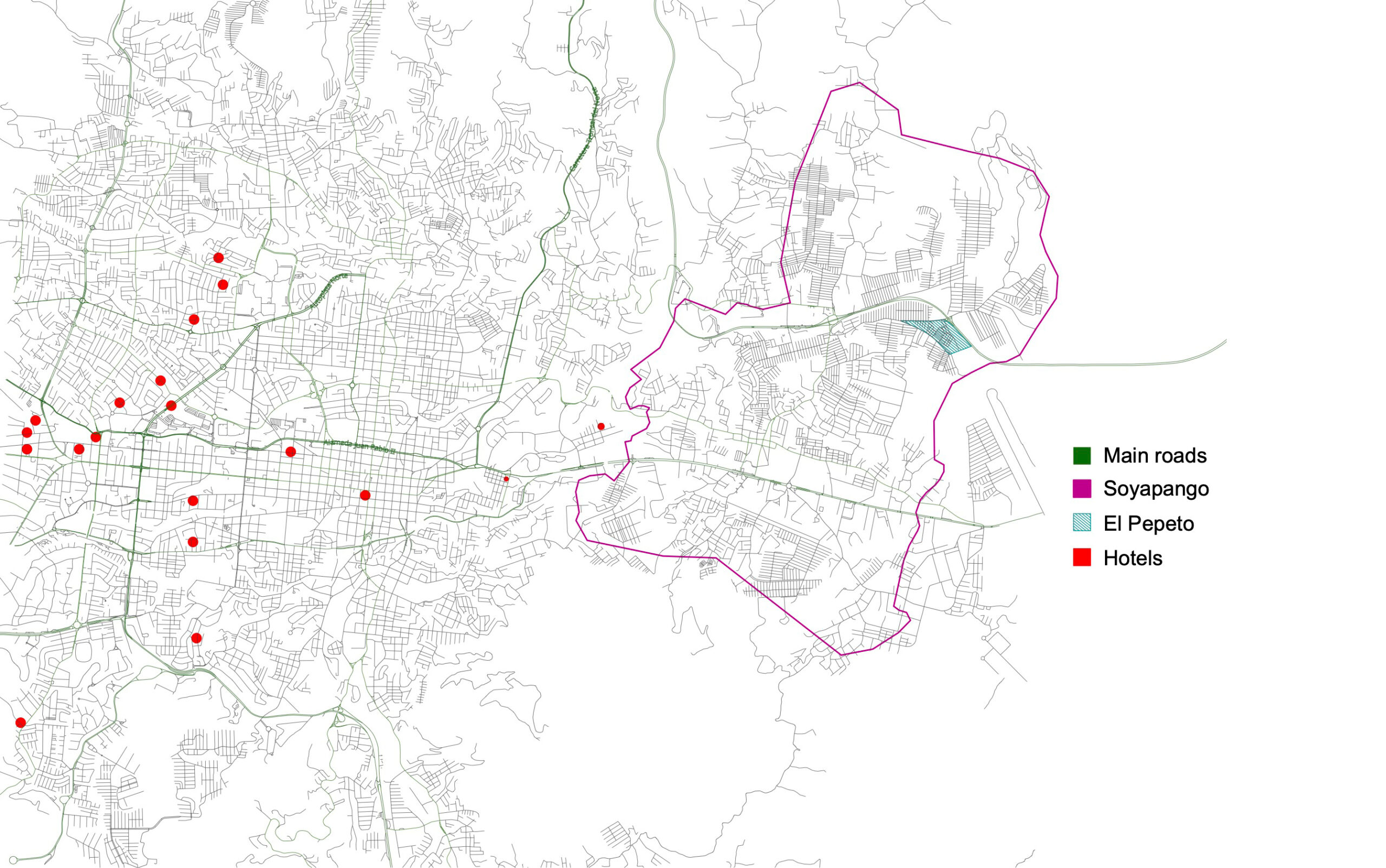

A change in US immigration policy brought about a strong change in the architectural urban environment as well as in the behavior of the people in Colonia El Pepeto. The 1997 US immigration reform, which aimed to deport people with criminal backgrounds to their country of origin, led to the rapid rise of the youth gangs MS-13 and Barrio 18 in Central America.

Poorer areas such as Soyapango, including the Colonia El Pepeto neighborhood where the sites-and-services project is located, were particularly affected.

The presence and control of gangs affects both the use and behavior of residents in public and private spaces. There are times when people are not allowed to leave the house. Even urban spaces such as playgrounds are often empty. Entrances, windows, and balconies that used to be open have often been completely barred over time. In Colonia El Pepeto itself, there are comparatively few reports of criminal activity on the streets, which is strongly related to the fact that all the streets of the neighborhood are lit. According to some reports and news, however, some gang members seem to live mainly in the houses of Colonia El Pepeto. There have also been several attempts to set up a gang base, which have so far been prevented by police intervention. However, it can be assumed that Colonia El Pepeto feels safer than other parts of Soyapango because of the lit streets. This feeling of safety is also supported by the large football fields and the school, which form a large public square where many people gather.

The degree of security of Colonia El Pepeto can be interpreted from the number and positioning of hotels. It can be assumed that larger tourist facilities and hotels especially tend to be located in safer places. In the San Salvador area, there are still many hotels, but this changes abruptly when one looks at the Soyapango district, where suddenly not a single hotel appears on the map, apart from a few located directly on the border with San Salvador or on the main road.

Due to the circumstances and different aspects, one can assume that Colonia El Pepeto is a comparatively safe place for locals without big gang conflicts, but for people from abroad it is not the safest place, especially if one takes into account that the influence of the gangs also aims to control the population living there. They control who is where, and register when strangers enter the area because of their well-connected infrastructure. The influence of gangs is by no means limited to the Soyapango area but is still a major problem in Central America today, affecting many communities.

Sources

Schmidt-Padilla, Carlos. “Gangs, Labor Mobility, and Development.” Matrix, University of California, Berkeley. 8 Apr. 2020. https://matrix.berkeley.edu/research-article/gangs-labor-mobility-and-development/.

Quora. “How dangerous is Soyapango in El Salvador and how do I stay safe?” 2016. https://www.quora.com/How-dangerous-is-Soyapango-in-El-Salvador-and-how-do-I-stay-safe.

Hamburger Abendblatt. “Töte, um zu Leben, lebe, um zu Töten,” 21 Jan. 2010. https://www.abendblatt.de/kultur-live/article107632019/Toete-um-zu-leben-lebe-um-zu-toeten.html.

Frankfurter Rundschau. “Im Gefährlichsten Land der Welt,” 10 Jan. 2019.

https://www.fr.de/panorama/gefaehrlichsten-land-welt-11111962.html.

La Noticia SV. “El periodismo necesita inversión, trabajo y esfuerzo. Para compartir esta nota usar nuestro portal de noticias.” https://lanoticiasv.com/capturan-a-dos-sujetos-que-pretendian-montar-un-punto-de-asalto-en-soyapango.

“Colonia El Pepeto, Jardines del Pepeto 2y Santos 3 Soyapango…” YouTube, uploaded by Soyacity 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxjcf-LJ4MY.

“Nuevo hundimiento en Vol. El Pepeto #Soyapango.” YouTube, uploaded by Noticias4VisionTCS, 3 Dec. 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XZ2ka-gw34w&t=1s.

“Soyapango El Pepeto 3.” Facebook, uploaded by Case en Venta, 3 May 2021. https://www.facebook.com/Casaselsalvador1988/videos/soyapango-el-pepeto-3/1364890393907205/.

Cover Image

Map of hotels in the surroundings of Soyapango. Source: Own work.

Community-Based Facilities & Programs

by Shreya Sen

The theme surrounding the provision of community facilities in the sites-and-services project, and in particular its afterlife, remains important. I seek to answer the question – which essential community-based facilities, programs, and initiatives form part of Colonia El Pepeto today, and to what extent has the sites-and-services program launched in the 1970s contributed to their development?

The FSVDM-initiated project intended to engage community building by means of 1 multi-purpose community center, 1 sports-field, 1 school, 2 parking lots, 1 park, and 3 roads along the perimeter of the site to allow access to transport infrastructure.1 Today, the evolution of the sites-and-services project is most evident in its appropriation and expansion of these community facilities.

The single sports field has expanded to 3, which highlights the value of play and leisure within the growing community. The local football and the junior football leagues have become a great source of pride and identity in Colonia El Pepeto.2 Additionally, the playgrounds and the community center also serve as a basis for educational programs. For instance, the NGO Fundación Salvador del Mundo (FUSALMO) works with the socially vulnerable youth of El Salvador and offers educational support for their development.3 Founded in 2001, its work is based around one of the sports centers in Soyapango, which is considered one of the main regions in El Salvador facing high levels of violence among youths, including those affected by gangs.3 Literacy programs initiated as part of the Colonia El Pepeto primary school, Centro Escolar Agustin Linares, and the community church seek to counter these issues of violence, marginalization, social exclusion, and stigma.4

The single sports field has expanded to 3, which highlights the value of play and leisure within the growing community. The local football and the junior football leagues have become a great source of pride and identity in Colonia El Pepeto.2 Additionally, the playgrounds and the community center also serve as a basis for educational programs. For instance, the NGO Fundación Salvador del Mundo (FUSALMO) works with the socially vulnerable youth of El Salvador and offers educational support for their development.3 Founded in 2001, its work is based around one of the sports centers in Soyapango, which is considered one of the main regions in El Salvador facing high levels of violence among youths, including those affected by gangs.3 Literacy programs initiated as part of the Colonia El Pepeto primary school, Centro Escolar Agustin Linares, and the community church seek to counter these issues of violence, marginalization, social exclusion, and stigma.4

An increased access to paved roads since the start of the sites-and-services project has enabled Soyapango’s mobile primary care brigade (specializing in general medicine, reproductive health, and clinical psychology) to access the neighborhood.5 This mobile unit is particularly important for the residents of Colonia El Pepeto, who face difficulty accessing health facilities. In addition, a comprehensive mental health initiative has been launched, aiding in the promotion of health-care practices within the social fabric of the community. These programs also take place in Colonia El Pepeto’s park and green spaces in the form of pop-up health services initiated by local social and community workers.

By tracing the development of these community facilities from their beginnings as part of a sites-and-services initiative to the programs today, it can be concluded that these social, cultural, and health-care interventions have become deeply integrated within the urban fabric of Soyapango. Through the appropriation and expansion of the initial programs, the infrastructure has been adapted to the needs and values of Soyapango today.

Sources

1. World Bank. El Salvador: Appraisal of a Sites and Services Project. 20 Sep. 1974.

2. “Fiesta navideña, Col. El Pepeto, Soyapango.” Facebook, uploaded by Efraín Guatemala, 9 Dec. 2020, https://www.facebook.com/efrainguatemalaNI/videos/404350114222026/.

3. Peace Direct. “Fundación Salvador Del Mundo.” Jan. 2016, https://www.peaceinsight.org/en/organisations/fundacion-salvador-del-mundo/?location=&theme.

4. Labios, V. “Our program is multiplying!” Salvador’s HOPE. 27 October 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022 from https://www.salvadorshope.org/blog/our-program-is-multiplying.

5. Médecins Sans Frontières. “El Salvador: MSF Facilitates Access to Healthcare in San Salvador and Soyapango.” Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International, 20 June 2018, https://www.msf.org/el-salvador-msf-facilitates-access-healthcare-san-salvador-and-soyapango.

Cover Image

Overview of community-based facilities and programs as part of Colonia El Pepeto, Soyapango today. Source: Own work, based on sources cited in text.

Hay El Salam

حيّ السلام

Ismailia, Egypt

1978-1982

by Léna Grossenbacher, Raúl Hansra Sartorius, Clara Zuber

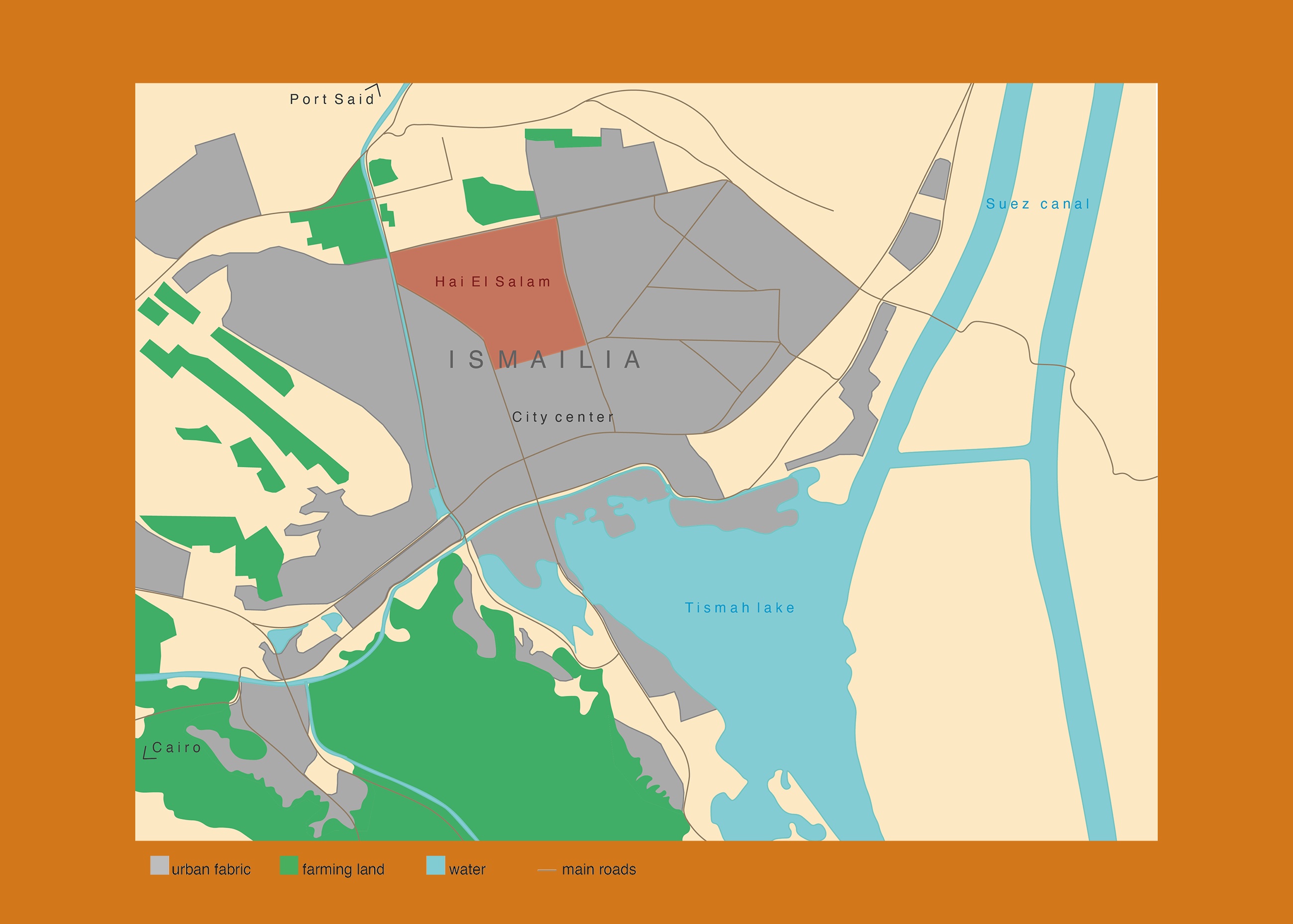

Ismailia is an Egyptian city founded in 1863 as the headquarters of the administration of the Suez Canal construction project, and is located west of the canal. The city, built by the French settlers, is divided into 3 quarters – Latin, Greek, and Arab – made of 5 identical modules ensuring order and regularity, with the exception of the Arab quarter, which eventually took on a checkerboard structure because the modules were not adapted to the locals’ way of life .1

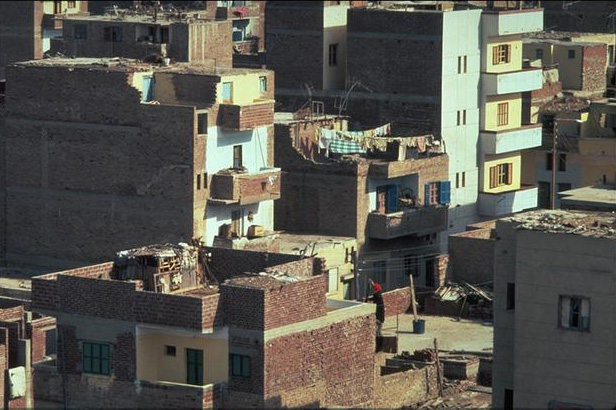

The Six-Day War of 1967 forced the inhabitants to leave the city and return only in 1974, joined by immigrants from El-Skarkia. As the state’s reconstruction program after the war was not efficient enough, people had to settle in slums. At that time, Hay El Salam’s area only had one-floor housings made with mud bricks, no electricity, limited access to water, and almost no services. The roads were irregular, unpaved, and covered with rubbish. 37,000 people lived there, most with low incomes.2

In 1976, the governorate entrusted Culpin and Partners with the study of a new masterplan of the city, with the idea of modernizing and rebuilding informal settlements such as Hay El Salam. This British architecture office, founded in 1968, had mainly focused on public and private projects in developed countries.3 The emphasis in their work was often put on the consolidation of decentralized development processes.4 After a year of low productivity, the British consultants were entrusted with a complementary study on the implementation of the project in 1977. They proposed an agency system to support the governorate with the management of the project: agencies were based in Hay El Salam to listen to the local communities, represent them in front of the other stakeholders, and shape a project in cooperation with them.5

The architectural and urban planning of the project took place in time with different phases, and in space with different zoning and plot allotments. Indeed, the Agency, following Culpin’s masterplan recommendations, set up basic services for inhabitants in the first phase. The plots were delimited, pit latrines installed, and standpipes set up every 150m for common use.6 The project then accounted for public and semi-private spaces and services, upgrading existing sewers and canalizations, bus lines, and roads. Housing was projected as a work whose shape would evolve as people installed themselves. The urban fabric was organized around a central area where common facilities like a mosque, a school, and a market were located.7

The target population of the project was mostly people with the same income as those already living in Hay El Salam (between 16 and 40 LE per month), but also some people with lower and higher incomes to make the cross-subsidy system of the plots possible.8 The inhabitants appropriated their plots quite freely. They had to respect the use of certain materials, but there was no predefined design. Their financial means, however, often limited them. It is possible to notice that, despite the regulations describing a façade finish, many houses/buildings still have their structure apparent, probably to save money.

To this day, the neighborhood is considered a pleasant place to live with a low crime rate. The project can therefore be considered a success. However, the very attractive conditions of the area have attracted many people with higher incomes who have bought land from the inhabitants. This reveals a weakness in the project, which was intended for a specific income group, and an important issue to investigate to draw lessons from the Hay El Salam project.

Sources

1. Montel, Nathalie. “Ismaïlia (Egypte): une ville d’ingénieurs.” Revue du monde musulman et de la Méditerranée, no. 73-74. 1994. pp. 255-56.

2. Madbouly, Mostafa. Participatory Slum Upgrading, Documented Experience from Ismailia, Egypt. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2011. p. A34.

3. Matteucci, Claudio. Long-term Evaluation of an Urban Development Project: The Case of Hai El Salam. 7th N-Aerus Conference. 2006. pp. 1-2.

4. Culpin Planning. “The Company.” https://www.culpinplanning.com/.

5. Ismailiyya Development Projects Project Brief. Compiled by the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. 2013. pp. 9-10.

6. Hai El Salam Project, an Upgrading and Sites-and-Services Project, Ismailia, Egypt. United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat), Nairobi. 1994.

7. Davidson, Forbes and Geoffrey Payne (eds.). Urban Projects Manual. Second Edition. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. 2000.

8. Hai El Salam Project, an Upgrading and Sites-and-Services Project. Op. cit. p. 17.

Cover Image

Improvement and appropriation of the plots by the inhabitants in different stages of construction. Source: Own work, based on the analysis of plans and photos.

Images

Cover Image: Improvement and appropriation of the plots by the inhabitants in different stages of construction. Source: Own work, based on the analysis of plans and photos.

Image I: Situation plan of Hay El Salam. Source: Own work, based on satellite photos.

Image II: Stakeholders involved. Source: Own work, based on the diagram found in: Blunt, Alistair. “Ismailia Sites-and-Services and Upgrading Projects — A Preliminary Evaluation.” Habitat International, vol. 6, no. 5-6. 1982. p. 588.

Image III: Plan of the old and new Hay El Salam, as well as of the new infrastructures. Source: Own work, based on: Davidson, Forbes and Geoffrey Payne (eds.). Urban Projects Manual. Second Edition. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. 2000. pp. 78, 149; Hai El Salam Project, an Upgrading and Sites-and-Services Project, Ismailia, Egypt. United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat), Nairobi. 1994. pp. 49-54.

Image IV: Gradual improvements in the neighborhood, c. 1986. Source: “Ismailiyyah Development Project: Recipient of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1986.” https://www.archnet.org/sites/167. Photograph by Culpin Planning.

Image V: Night photo of the neighborhood in 2007. Source: Forbes Davidson Planning. “Ismailia: Hai el Salam post 2007.” https://forbesdavidsonplanning.com/?page_id=1805. Photograph by Forbes Davidson Planning.

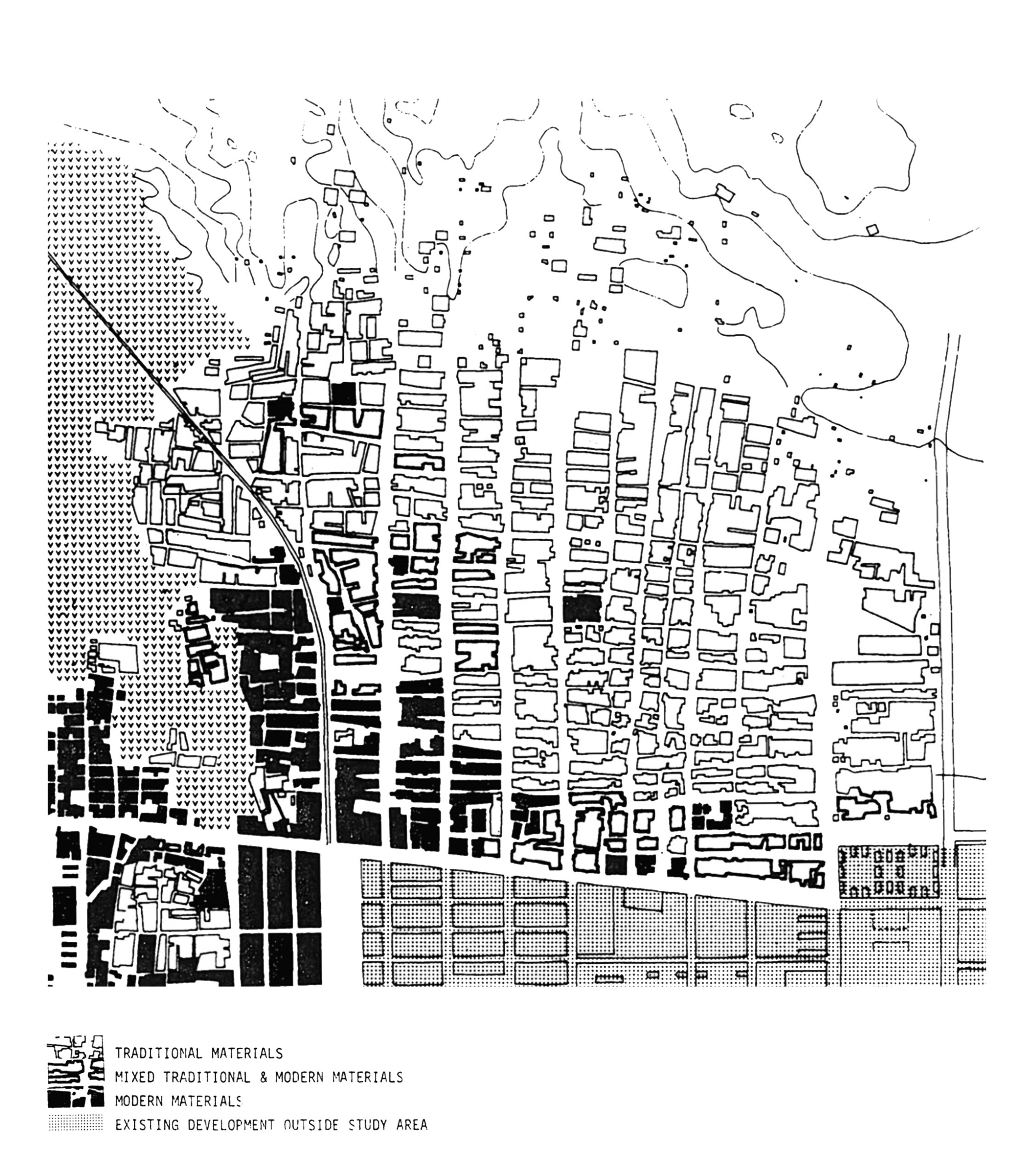

Materials and Social Injustice

by Léna Grossenbacher

The existing part of the Hay El Salam neighborhood before the implementation of the sites-and-services project was composed of a majority of traditional mud constructions. In its southern part, it was also possible to find some larger ones in cement and sand blocks, fired bricks, or reinforced concrete structures. The prices of these different materials and the image they convey vary enormously. 1 Earthen dwellings, which are very affordable, are perceived as the homes of the poorest people, while reinforced concrete buildings, which are larger and more solid and therefore more expensive, indicate a higher social status. If they could afford it, the locals avoided building in raw earth for this reason.2

In developing the project, no restrictions on the use of any of these materials were made. However, the possibility of densification was very different from one dwelling to the other. For example, a mud house could not be more than one story high.3 Inhabitants often chose the type that suited their financial means. Later, if they had been able to acquire more money, they would expand their home. Sometimes they had to destroy the existing base and rebuild it with material that allowed them to add floors.4

In the framework of the project study, problems with the supply of materials had already been anticipated. Some strategies were supposed to limit these issues,5 but few were effective, leading to higher prices for materials, as well as supply difficulties. Despite the loan system in place, some owners could no longer afford to buy their construction materials.6

In parallel, the governorate, which had tolerated the use of bricks and mud for years, decided to ban them in the Hay El Salam area in 1982. For them, these materials were too reminiscent of the aesthetics of the informal housing that existed in the area. Access to the most affordable material was therefore made impossible for the inhabitants of the neighborhood.7

The impossibility of developing their plot, as well as the likely increase in the price of living in the district, are presumably the causes of the departure of a large part of the low-income population. The demand for plots in the area from higher income earners may have also encouraged them to sell. Thus, the initial purpose of mixing different social classes was partly a failure.

Sources

1. Clifford Culpin and Partners et al. for ODA. Ismailia Demonstration Projects, Volume 1: Proposals. 1978. pp. 32-33.

2. Matteucci, Claudio. Long-term Evaluation of an Urban Development Project: The Case of Hai El Salam. 7th N-Aerus Conference. 2006.

3. Clifford Culpin and Partners et al. for ODA. Ismailia Demonstration Projects, Volume 2: Technical. 1978. pp. 90-91.

4. Sudra, Tomasz. “The Case of Ismailia: Can Architect and Planner Usefully Participate in the Housing Process?” In Housing: Process and Physical Form, ed. by Linda Safran. Philadelphia: Aga Khan Award for Architecture. 1980. p. 53.

5. Culpin et al. Ismailia Demonstration Projects, Vol. 2. Op. cit. pp. 92-94.

6. Matteucci. Long-term Evaluation. Op. cit. p. 7.

7. Ibid.

Cover Image

Research in the literature on the history of materials management during the project and the injustices that resulted. Source: Own work, excerpts from:

1* Clifford Culpin and Partners et al. for ODA. Ismailia Demonstration Projects, Volume 1: Proposals. 1978.

2* Clifford Culpin and Partners et al. for ODA. Ismailia Demonstration Projects, Volume 2: Technical. 1978.

3* Silcox, Stephen. A Comparative Evaluation of Three Upgrading Projects in Egypt (Helwan, Manshiet Nasser and Ismailia): A Replicable Analysis. Ford Foundation. April 1985.

4* Sudra, Tomasz. “The Case of Ismailia: Can Architect and Planner Usefully Participate in the Housing Process?” In Housing: Process and Physical Form, ed. by Linda Safran. Philadelphia: Aga Khan Award for Architecture. 1980.

5* Matteucci, Claudio. Long-term Evaluation of an Urban Development Project: The Case of Hai El Salam. 7th N-Aerus Conference. 2006.

6* Tadamun. “‘Land & Services’ Policy: What We Need to Learn from the Experience of the al-Salām District in Ismāʿīlīya.” 2019. https://www.tadamun.co/?post_type=initiative&p=10455&lang=en&lang=en.

7* “Ismailiyya Development Projects.” In Space for Freedom, ed. by Ismaill Serageldin. London: Butterworth Architecture. 1989.

Beyond the Fields Lived

by Raúl Hansra Sartorius

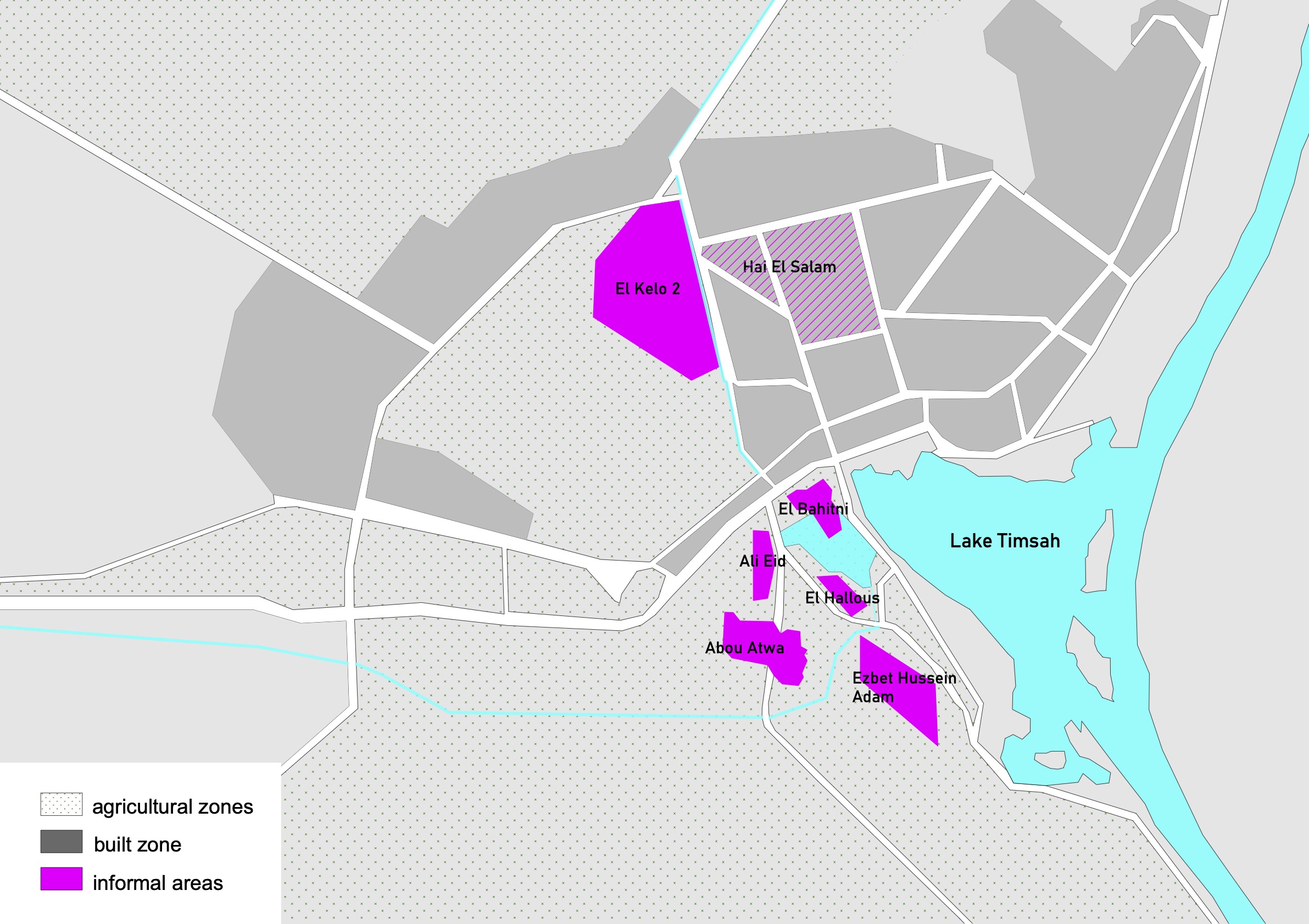

Strawberry fields forever? Not really. Squeezed between agricultural lands on the west and the east, the horizontal urban development of Ismailia was restricted in previous masterplans.1 However, most of the urban expansion from the end of the 1980s to the present day took place through illegally subdividing agricultural lands.2 Located next to each other, Hay El Salam and El Kelo 2, also called Al Hejaz, are separated by a canal of Lake Timsah. The particularity is that El Kelo 2 is built on what was classed as agricultural land. By studying different satellite images from 1985 to 2022, there is a clear urbanization taking place on these agricultural fields, echoing the development of the sites-and-services in time. As such, I seek to investigate the links between the informal settlements of El Kelo 2 and Hay El Salam, especially due to their direct spatial proximity.

In 2006, an official census estimated the total inhabitants of Ismailia to be about 303,000, including 73,000 people in Hay El Salam.3 The Ministry of Local Development estimated the population living in informal settlements to be 185,000 inhabitants, roughly 59% of Ismailia’s urban population, divided between 7 different locations.4 The estimated population of El Kelo 2 was 5,800 inhabitants. Moreover, with 75% of all informal settlements on agricultural lands, El Kelo 2 did not differ from most cases.

After the directories for the Ismailia masterplan were decided in 1976, the work firstly focused on the informal settlement of what is now Hay El Salam.5 Initially a success in targeting the low and very-low income group, many of these inhabitants were, through different means, pressured to move away around 1985. One blatant reason was the forbidding of low-cost traditional building techniques by the governor of Ismailia in 1982.6

In the 1990s, aware of the urban expansion problems Ismailia was to face, different sites were examined to respond to the housing need of the city, and El Kelo 2 was a potential candidate for the Hay El Salam sites-and-services project to be replicated. Indeed, this is what seemed to happen, and by 2007, officials decided to finance a local network of basic infrastructures. Though well-built in reinforced concrete, the area lacks public services and transgresses on state land and property.7

The analytical drawing aims to retrace the informal settlement of El Kelo 2, comparing its development with that of Hay El Salam and considering the various actors and parameters, in the form of sectional drawings and an actors’ timeline. Tackling the disappearance of agricultural land through urbanization and social inequalities, this also highlights a broader situation that is occurring around Ismailia.

Sources

1. Culpin Planning. Ismailia Development Project. 1986.

2. Madbouly, Mostafa and Ghada Hassan. Participatory Slum Upgrading Documented Experience from Ismailia, Egypt. UNDP. 2011.

3. Ibid.; “Ismailia.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ismailia (last consulted on 04.12.2022).

4. Ibid.

5. Davidson, Forbes and Geoffrey Payne (eds.). Urban Projects Manual. Second Edition. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. 2000.

6. Madbouly and Hassan. Participatory Slum Upgrading. Op. cit.; Matteucci, Claudio. Long-term Evaluation of an Urban Development Project: The Case of Hai El Salam. 7th N-Aerus Conference. 2006.

7. Madbouly and Hassan. Participatory Slum Upgrading. Op. cit.

Cover Image

Beyond the Fields Lived: El Kelo 2 & Hay El Salam. Timeline, relationships, and influences. Source: Own work.

Semi-Private Spaces: Protected Spaces in a Growing City

by Clara Zuber

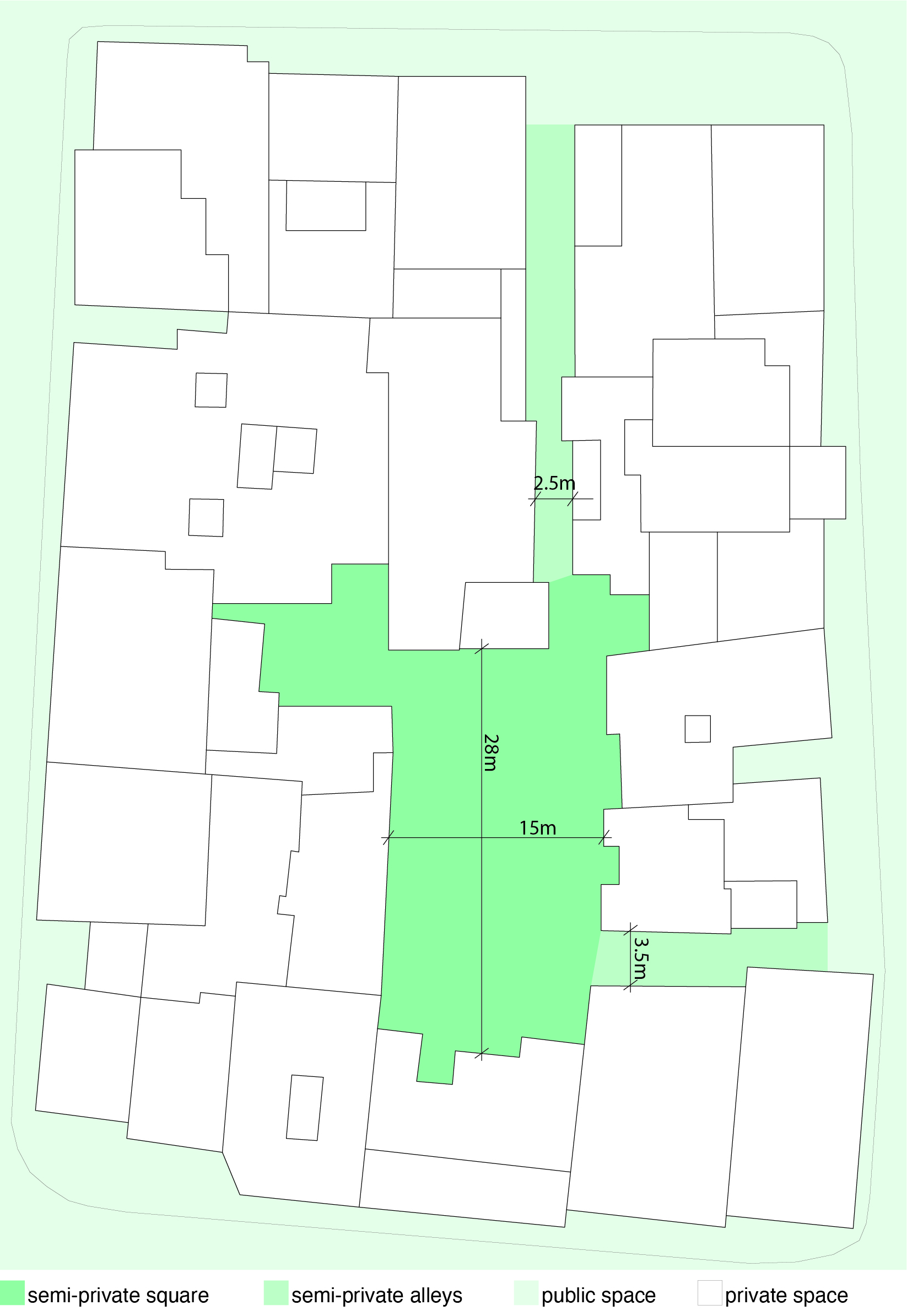

During the design phase of the Hay El Salam project, the architects of Culpin and Partners took care to plan different types of outdoor spaces. They are divided into 4 categories: public spaces (streets, squares, etc.), semi-public spaces (schools and other specialized institutions), semi-private spaces (small neighborhood squares, small alleys, etc.), and private spaces (houses).

Already during the study phase of the site, Culpin and Partners had noticed that small children played in the east–west streets, which were devoid of cars. These streets were also used by the inhabitants for sitting outside. Older children and men played soccer on most of the other streets.1 Knowing that the new project would result in a significant expansion of the population, the architects wanted to restrict these semi-private recreation spaces to dedicated areas, away from traffic and crowds.2 Looking at the city as it is today, these spaces make more sense than ever. The streets of Hay El Salam are now filled with cars and people, yet it has become a big living city.

A crucial point in the design of these semi-private protected spaces is their dimensions. The architects do not seem to have given any precise indication regarding this. One wonders today if they had foreseen that the inhabitants would build houses of up to 6 floors. The drawings they made showing how the inhabitants would appropriate the space suggest that they did not, since they drew dwellings of just 2 to 3 floors high. The semi-private spaces, now squeezed between buildings exceeding 10m in height, will gradually lose their pleasant qualities if the excessively high buildings prevent proper sunlight and create narrow, higher than wide spaces. These possible spaces risk becoming unhealthy and unpleasant, and it would be a great loss for the city to be deprived of such important and meaningful spaces for the inhabitants.

Sources

1. Culpin Planning. Ismailia Development Project. 1986.

2. Madbouly, Mostafa and Ghada Hassan. Participatory Slum Upgrading Documented Experience from Ismailia, Egypt. UNDP. 2011.

3. Ibid.; “Ismailia.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ismailia (last consulted on 04.12.2022).

4. Ibid.

5. Davidson, Forbes and Geoffrey Payne (eds.). Urban Projects Manual. Second Edition. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. 2000.

6. Madbouly and Hassan. Participatory Slum Upgrading. Op. cit.; Matteucci, Claudio. Long-term Evaluation of an Urban Development Project: The Case of Hai El Salam. 7th N-Aerus Conference. 2006.

7. Madbouly and Hassan. Participatory Slum Upgrading. Op. cit.

Cover Image

Study of the quality of space and sunlight in semi-private areas. Source: Own work, based on Google Maps observations.

This online exhibition is co-produced by course tutors and participating students as part of the Autumn 2022 seminar course ‘The City Lived: Sites-and-services’.

Course Tutors:

Sebastiaan Loosen, Lahbib El Moumni

Students:

Pierre Eichmeyer, Leandra Graf, Léna Grossenbacher, Victor Kleyr, Amélie Lambert, Lars Ludes, Raúl Hansra Sartorius, Shreya Sen, Julia Tanner, Clara Zuber

Guest Lecturers & Guest Reviewers:

Luce Beeckmans, Hannah le Roux, Petros Phokaides

Teaching Assistant:

Sereina Fritsche

Online Exhibition Support:

Sereina Fritsche, Leandra Graf