Her Agency

Students explored the life and work of “female professionals” (urban designers, architects, politicians, journalists, editors, curators, philanthropists, etc.) in the post-war period who started to critically engage in discussions on urban design and actively contributed to the design of cities.

- {{ item.label }} {{ item.address }}

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy

1903-1971

USA

Look Them in the Eyes, and Prove Them Wrong

In the bustle of a small Berlin theatre, the heavy camera is placed on a stand. We are in the 1920s; during the shot, which lasts several seconds, Sibyl Pietzsch stares at the lens, her gaze insolent and graceful, without blinking. She is about to go on stage, to take the first steps of an emancipation that she will strive to pursue throughout her life. She was a secretary, a bookseller, an actress, a playwright, a wife, a mother, a widow, a professor, a critic, a theorist: for Sibyl Pietzsch, later Moholy-Nagy, devoting herself to urban design was a much broader role than simply drawing up a master plan.

Image Caption: Sibyl Moholy-Nagy ca. early 1930s, during her days as an actress in Weimar, Germany.

Image Credits: Estate of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society, New York.

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy was an architectural and art historian. Originally a German citizen, she moved to the USA in 1937 with her second husband, the Hungarian Bauhaus artist, László Moholy-Nagy. After his death, she worked as a journalist, teacher and academic. She was critical of the modernist movement and its leaders, notably for their lack of sensitivity to the site and their ideological way of building. Nevertheless, she was interested in functionalist thinking, though she found its expression in anonymous architecture that ‘was preserved for no other reason than its adequacy beyond the life of the builder.’ [1]

She taught at the Pratt Institute in New York for twenty years [2], whilst working as a critic for major architecture magazines such as Progressive Architecture and Architectural Forum. She also published pioneering books concerning vernacular architecture and the history of the urban environment, such as Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture and Matrix of Man: An Illustrated History of Urban Environment.

As a professor, she lived long in her students’ memories by capturing their attention, and bringing to light her conviction of the importance of vernacular architecture. She was also convinced of the relevance of constructions without architects, and taught an urbanism history starting with the first settlements, established in different regions of the world, with judicious architecture adapted to climate, materials and geography. Her sharp eye and independent mind were not impressed by modernist masterpieces made of glass and steel, or well-drawn masterplans. Rather, she was interested in anonymous buildings, and observed spontaneous urban fabric, analysing their qualities. As a journalist, Sybil Moholy-Nagy did not hesitate to criticise the functionalism in vogue in the 1950s.

In her writing, she forged a unique voice and style, sharp and courageous, directly attacking respected architects and incorporating a political dimension in her architectural critiques. She claimed that the import of German functionalism had destroyed the vitality of indigenous American architecture, and that functional architecture was no longer providing the urban and architectural qualities it once possessed. [3]

In her books, she developed a history of architecture against the narrative of her time. Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture (1957) highlights how attention to site, local materials and climate generated a strong vernacular tradition. Matrix of Man: An Illustrated History of Urban Environment (1968), which explored the physical forms of cities from Classical Greece to the present day, argued for the generation of urban form starting from site-specific characteristics, at a time when many planners were imposing a unified approach to urban planning and renewal. Proving the importance of vernacular architecture and site-generated urbanism, rather than design and ideology, Moholy-Nagy made a lasting impression on architecture history. Her works are nowadays considered as references of architectural culture, and scholars have recently conducted extensive research on Moholy-Nagy and her contribution to architecture history and urbanism. [4]

Working hard to bring her convictions to light, Sybil Moholy-Nagy was an important voice on the post-war architectural scene in the United States. She also contributed to the increasing interest in the urban and historical dimensions of architecture, which is linked to the idea that urban design is not supposed to impose the new, but rather react to the existing.

Oana Popescu

1 Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl. Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture. Horizon Press, 1957.

2 She had also been guest professor at other universities, including Braunschweig, Houston and Columbia.

3 Her critical attitude culminated in her 1968 article, “Hitler’s Revenge,” which begins as follows: “In 1933 Hitler shook the tree and America picked up the fruit of German genius. In the best of Satanic traditions some of this fruit was poisoned, although it looked at first sight as pure and wholesome as a newborn concept. The lethal harvest was functionalism, and the Johnnies who spread the appleseed were the Bauhaus masters Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer.” Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl.“Hitler’s Revenge.” Art in America, September–October 1968: pp. 42-43.

4 The researcher Hilde Heynen has written a book about Moholy-Nagy, in a series edited by Tom Avermaete and Janina Gosseye: Sibyl Moholy-Nagy: architecture, modernism and its discontents. Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019.

Carmen Velasco Portinho

1903-2001

Brazil

A Lifelong Fight for Women’s Emancipation

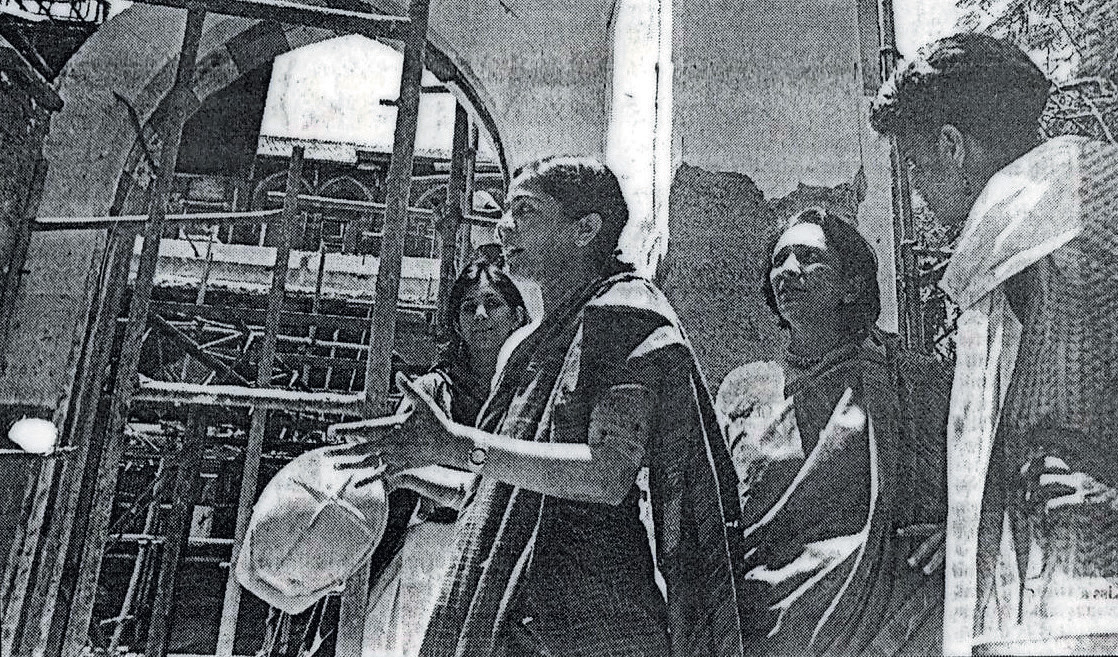

In this picture, we can see the engineer and urban planner Carmen Velasco Portinho on the construction site of the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro, for which she carried out the engineering work. [1] Holding a paper in her hands, and adopting a confident posture, Portinho is explaining something to a man beside her. In the background are two other men, wearing working clothes and construction helmets. The picture was taken around 1950, a time when, in Brazil, the engineering and construction working fields were generally restricted to men. But Portinho was an exception. Standing in the foreground, she clearly has the leading role: her professional achievements, as a civil engineer and urban planner, were considered equally important to those of her male colleagues. [2]

Image Caption: Carmen Portinho at the construction site of the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, 1950.

Image Credits: Unknown

At the beginning of her career, she was in charge of the implementation of electric installation in all municipal buildings of the city of Rio de Janeiro, and conducted multiple remodellings of houses. [3] Later, she worked with her husband, Affonso Reidy, designing the living complex Prefeito Mendes de Morais as well as the headquarters of the Museum of Modern Art. In her sixties, Portinho became the director of the School of Industrial Design of Rio, and was later an advisor at the Technology and Science Centre of the State University in the same city.

To achieve her goals, Portinho had to fight hard for women’s emancipation and equal rights. In her private life, she pursued her own individual independence by starting work, as a mathematics teacher at a male boarding school, at a very early age. There, she had to confront the opposition of the Minister of Justice, who didn’t agree with her methods. Later, she had to prove herself once more against her male superiors, who challenged her to climb up a roof to fix a lightning rod of a city hall building [4]. Portinho proved her validity by effortlessly conquering this ‘masculine’ endeavour. Consequently, from that moment on, she wore trousers to work, like her male colleagues, in so doing pushing through gender equality in the working field.

On the professional level, Portinho took major decisions in her urban designs to help women gain more independence, such as including a cleaning service provided by professionals into the actual programme of the building, allowing women to dedicate their time to other matters, such as work.

Portinho also advocated women’s rights in the different institutions where she received her education, such as the Polytechnic School of Rio de Janeiro, where she founded the Brazilian Federation for Feminine Progress. She aimed for mutual support between women, and to defy current oppressing normativism. She also established the Brazilian Association of Engineers and Architects, through which she encouraged women graduates to enter the job market. Portinho took a major step in her fight for women’s emancipation when, around the year 1930, she convinced the then-president of Brazil, Getulio Vargas, to give the right to vote, not only to literate women, but to every single adult woman in the country. [5]

Carmen Portinho was a major figure in the history of Brazilian women’s fight for autonomy. She had a diverse approach, confronting this matter through the social aspect and advocating women’s rights in her private life, but also combining it with the spatial aspect, for example including an automated collective laundry system into the design of the building, transforming, through the built environment, the socio-cultural conditions of woman.

Alejandra Schmid

1 Carmen Portinho at the construction site of the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, 1950. “Carmen Portinho e a construção do MAM-Rj.” Mulheres na Arquitetura Brasileira. 2 Apr. 2014. Web. mulheresnaarquiteturabrasileira.wordpress.com/2014/04/02/carmen-portinho-e-a-construcao-do-mam-rj . Accessed 4 May 2022.

2 Carmen Portinho graduated in 1924 as a civil engineer at the Polytechnic School of Rio de Janeiro, and read for her postgraduate qualifications as an urban planner in 1926 at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “Carmen Portinho.” Wikiwand, n.d. www.wikiwand.com/es/Carmen_Portinho. Accessed 30 March 2022$

3 Ghisleni, Camilla. “Carmen Portinho and the Vanguard of Modernism in Brazil.” Trans. Diogo Simões. ArchDaily, 1 February 2022. Web. https://www.archdaily.com/975890/carmen-portinho-and-the-vanguard-of-modernism-in-brazil. Accessed 4 May 2022

4 Wanderley, Andrea. “Série ‘Feministas, graças a Deus!’ VIII – A engenheira e urbanista Carmen Portinho (1903–2001).” Brasiliana Fotografica, 6 April 2021. Web. brasilianafotografica.bn.gov.br/?p=22326. Accessed 4 May 2022.

5 Wanderley, Andrea. “Série ‘Feministas, graças a Deus!’ VIII – A engenheira e urbanista Carmen Portinho (1903–2001).” Brasiliana Fotografica, 6 April 2021. Web. brasilianafotografica.bn.gov.br/?p=22326. Accessed 4 May 2022.

Lin Huiyin

1904-1955

China

‘Lady of Letters’ from old buildings to modern Beijing

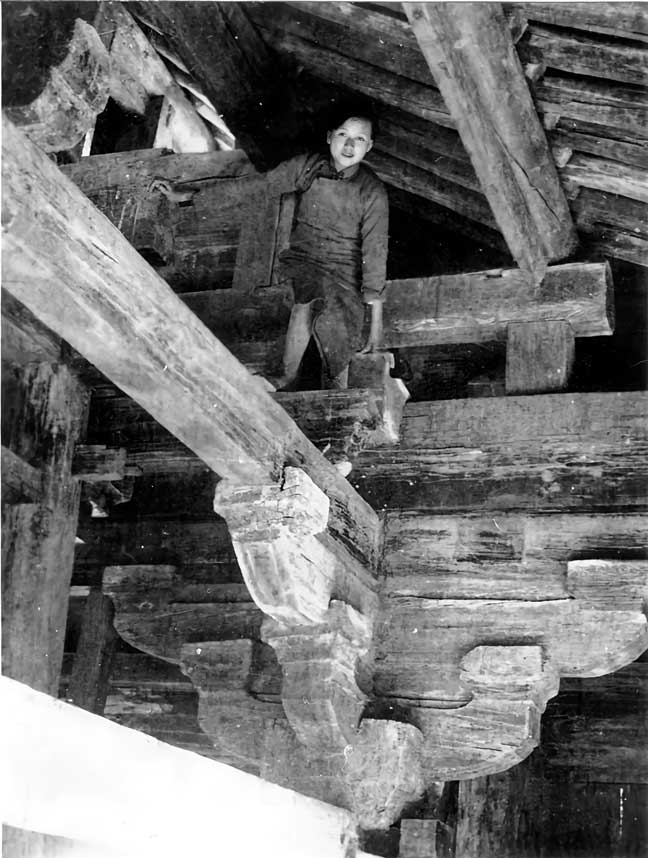

In this photograph, we can see an ancient, traditional wooden structure. Contrasting with the massive wooden beams is a small female figure that quickly captures our attention. Wearing an elaborate traditional Chinese cheongsam, the woman is leaning slightly forward on the edge of a wooden bracket, her eyes brightly lit with excitement. Despite her clothing and customs, the woman has climbed the roof to measure the dimensions of the structure. This woman, who played many roles, including that of poet and salonnière[1], is Lin Huiyin. Huiyin was modern China’s first female architect, as well as an architectural historian and urban planner. Along with her work related to architectural design and teaching, she and her husband, Liang Sicheng, were dedicated to preserving old buildings. [2] This photo, taken in November 1933, is a record of Huiyin’s research at Kaiyuan Temple [3],, one of China’s oldest surviving wooden buildings, which was a positive outcome of her focus on restoring Chinese cultural heritage sites.

Image Caption: Lin Huiyin in Kaiyuan Temple, Zhengding, China, 1933.

Image Credits: Photo Liang Sicheng.

During the decade after the photo was taken, Huiyin continued to document China’s ancient buildings, even though she suffered from tuberculosis and repeated relocation to escape from Japan’s invasion of China during World War II. Between 1930 and 1945, Huiyin and her husband visited more than 2,000 ancient buildings in China. The couple’s research enabled many of these buildings to survive and gain national and international recognition. Huiyin’s work not only filled numerous gaps in the history of ancient Chinese architecture, but provided the basis for her subsequent proposals to preserve ancient cities and develop new urban planning methods.

The early years of the People’s Republic of China coincided with the peak of Huiyin’s architectural career. In 1949, she became a professor of architecture at Tsinghua University, and a member of the Beijing City Planning Commission in 1950. Her work was deeply rooted in Beijing’s cultural and historical heritage, and expressed her aesthetic ideals. However, most of Beijing’s old neighbourhoods were demolished to achieve Chairman Mao’s plan to build a modern socialist capital.

Huiyin translated Soviet theories on post-war urban planning, and also created specialised visions of urban planning and reconstruction. Her proposal focused on building a new administrative centre for government buildings in Beijing’s western suburbs, which involved transforming the city walls and gate towers into gardens and public spaces where Beijing residents could relax and exercise. Unfortunately, the government rejected this proposal. In 2020, however, The People’s Government of Beijing announced that a park would be built along the Second Ring Road, where the ancient city wall formerly stood, to show the modern capital’s historical and cultural landscape: exactly what Lin had suggested seventy years ago.

From old buildings to modern Beijing, Huiyin walked the line between Preservation and Reconstruction. As her closest friends, Wilma and John K. Fairbank, said, in her life, Huiyin tried to respond to ‘the necessity to winnow the past and discriminate among things foreign, what to preserve and what to borrow.’ [4]

Xinyi Li

1 A salonnière was a woman who hosted intellectual gatherings, or ‘salons.’ In the 1930s, Huiyi was a charismatic hostess and the guiding spirit of ‘Madam’s Salon,’ a regular gathering place and influential cultural salon in Republican Beijing.

2 Huiyin graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1927. Despite her desire to attend the university’s department of architecture in 1924, Lin was not admitted, due to her gender. Even so, she was able to find a way to work as a part-time assistant in the architecture department by taking a course in the school of fine arts.

3 Kaiyuan Temple (simplified Chinese: 开元寺) is located in the old city of Zhengding, Hebei Province, China. It is a Chinese Buddhist temple from the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD).

4 Architectuul Community. “Lin Huiyin, China”, Web. https://architectuul.com/architect/lin-huiyin. Accessed 15 April 2022.

Erica Mann

1917-2007

Nairobi, Kenya

Erica Mann, a young white woman, probably in her late thirties or early forties, is standing in a grassy landscape in the countryside near Nairobi, Kenya. Behind her are five black men carrying objects on their heads. The photo shows Mann in a confident posture, wearing robust trousers and a headscarf. It portrays a woman accustomed to working in the fields and under the sun. A woman eager to take on projects, share ideas, have conversations with indigenous people and encourage women in the field of men. Mann was a foreigner in Kenya, and yet, in this picture, her upright standing position makes her seem self-confident and comfortable in her surroundings, as if she had been there for a long time and is the person in charge.

Image Caption: Erica Mann photographed in the early 1950s in the countryside around Nairobi.

Image Credit: Kenny Mann.

Before being forced to leave her home in Romania in the 1930s, Mann was trained at the École des Beaux Arts, Paris, where she already had to prove herself as the only woman in a class of three-hundred men. Together with her husband, she later fled Romania, and finally settled down in the countryside near Nairobi.

After having brought up her three children on their farm among the Masai, Mann took a job at the Kenya Lands Department, where she worked on the Masterplan of Nairobi and, later, on the city of Mombasa. She was soon recognised as a talented and committed urban planner, and became the senior planning and development officer for many major projects in Kenya, in charge of researching and gathering evidence for strategic planning decisions.

Mann considered herself a socialist. Her interest lay in the science of human settlements, including regional, city, community planning and dwelling design, with a holistic approach to planning harmonious human settlements and traditional African house designs, repudiating any idea that they were ‘primitive.’ She not only designed, but also lectured internationally on the subject, becoming a representative of post-colonial Kenya. Her interests broadened out to sustainable development and human rights issues. She furthermore founded two magazines, Build Kenya and Plan East Africa. Even when, in 1963, Kenya became independent, she continued working for the government, unlike many of her friends, who left the country. Furthermore, she and her husband engaged actively in the community, and frequently hosted ‘open house’ afternoons for the so-called ‘intelligentsia’ of Kenya.

In 1972, Mann founded the Council for Human Ecology: Kenya. The same year, she also founded the Women in Kibwezi rural development project [1], which intended to protect the environment of Kenya and empower rural women by supporting them in building self-sufficiently, training them in apiculture, brickmaking and rabbit breeding and, furthermore, granting security of tenure and the right to property titles. Mann saw urban planning as ‘an ideal profession for a woman because it builds on her innate capacity for providing an orderly and aesthetic environment for herself, her family and the community in which she lives.’ [2]

Erica Mann acted as an international ambassador, presenting her vision of post-colonial Kenya. She was aiming to create something for the city by developing and building new parts of Nairobi. [3] To do so, she created a platform to enable a dialogue between the people: between the ‘intelligentsia,’ politicians and indigenous communities. Furthermore, through her projects Mann empowered rural women to stand on their own feet.

Leandra Graf

1 The „Women in Kibwezi rural development project“ was judged as one of the 100 best practices in the world at the United Nations Habitat II conference in 1996.

2 Beautiful Tree, Severed Roots. Dir. Kenny Mann, 2014. Film.

3 In 2003, Mann was honoured with the title of Architect Laureate for Kenya.

Margaret Feilman

1921-2013

Australia

The Pioneer that Never Wanted to Start from Scratch

In this photograph from 1952, Margaret Feilman is standing in the Western Australian bushland on the site that will become Kwinana town. [1] She is using a twig as a pointer to explain a large map of the new satellite town to members of the state cabinet of Western Australia. Surrounded by male politicians, she is standing alone: the only woman and the expert planner, both isolated and distinct. In the foreground, at least two of the men are encroaching on her plans, feeling the need to help her hold them. The faces and postures of the men show a variety of interest levels. Some seem to be paying close attention, while others are not as eager to listen.

Image Caption: Margaret Feilman on site in Medina.

Image Credits: Unknown

The appointment of Feilman as planner for the Kwinana town project was considered bold. In the mid-1950s, planning was still a heavily male-dominated field in Australia. [2] Moreover, she was just 32 years old, and had only recently opened her own practice in 1950. [3]

Feilman gained her first experiences in town planning when, in 1945, as a new and young architect, she was part of a group tasked with rebuilding Australian towns destroyed during World War II. [4] There she realised that, with this work, she could make tangible improvements to people’s lives, particularly women and children from lower socio-economic backgrounds. [5] She said that the aim of planning should be ‘to make houses fit the population and not the population to fit into housing that was available.’ [6]

This anecdote illustrates how hands-on Feilman was. She was always involved on-site, and she placed great value on a detailed engagement with the existing site and community. She continuously pushed for planning strategies that would lead to the betterment of communities, especially in aspects like education and health.

This experience made Feilman believe that people needed a connection to the past. For her, preserving the built and natural heritage of a site was vital to town planning. [7] She was instrumental in bringing heritage considerations into the planning processes in Australia. [8] In her active planning work, this philosophy led her to participate directly on site. In an interview, she told the story of how she rode around the Kwinana town site on a bulldozer, pointing out all the trees to avoid during site clearing. [9]

To fulfil these goals, Feilman was convinced that people needed to be involved in planning processes. To educate them about the benefits of planning, she went to great lengths to give speeches and lectures, notably in remote rural communities. Her records show that she answered every letter she received from the communities she worked in as a planner. [10]

As seen in the image, Feilman was also interested in educating political decision-makers and public officials about the benefits of town planning. She made great efforts to support regional and local townships in establishing planning schemes that would work with their limited funding, [11] without compromising the worth of her own work. [12]

Despite her obvious enthusiasm and passion for her career, Feilman did not advise other women to pursue it, because it left little time for a personal and social life. [13]

Many of her ideas and agencies in the field of town planning are still felt today, and her legacy shaped many young architects and planners, both women and men. [14]

Dara Rüfenacht

1 Kwinana Town is her best-known project. Other notable planning projects include Mirrabooka (1951) and Edgwater Estate (1970). In total, she planned new towns and suburbs for over thirty local authorities across Western Australia. See Melotte, Barrie and Don Newman. “Vale Dr Margaret Anne Feilman OBE, Western Australian Town Planning Pioneer.” Planning Institute of Australia, 2013. Web. https://www.planning.org.au/newsletters/id/2554/idString/mwacb56581. Accessed 19 July 2022.

2 Davies, Amanda, and Julie Brunner. “A Review of the Practice and Legacy of Australian Planning Pioneer Margaret Feilman.” Australian Planner, vol. 54, no.1, 2017: 44.

3 When she returned from Great Britain with a graduate degree in town and country planning from the University of Durham, she was unable to find a job in a town planning position. As a result, she decided to open her own practice. See Davies, “A review of the practice and legacy of Australian planning pioneer Margaret Feilman”: 43.

4 Ibid.: 42.

5 Ibid.: 43.

6 “Interest in Lecture by Woman Town Planner.” Editorial. The West Australian. 23 Aug. 1950: p. 7.

7 Davies, “A review of the practice and legacy of Australian planning pioneer Margaret Feilman”: 49.

8 Melotte, Barrie. “Landscape, neighbourhood and accessibility: The contributions of Margaret Feilman to planning and development in Western Australia.” Planning History, vol. 19, no. 2/3, 1997: pp. 32-41, at 34.

9 Davies, “A review of the practice and legacy of Australian planning pioneer Margaret Feilman”: 45.

10 Davies, “A review of the practice and legacy of Australian planning pioneer Margaret Feilman”: 8.

11 She worked as a consultant preparing town planning schemes for more than twenty local authorities in rural areas and eleven metropolitan councils in Western Australia.

See Melotte, “Landscape, neighbourhood and accessibility”: 35.

12 Davies, “A review of the practice and legacy of Australian planning pioneer Margaret Feilman”: 8.

13 Ibid.: 6.

14 The Margaret Feilman papers can be found at the State Library of Western Australia. They include invitations, correspondence, plans, reports, petitions, photographs, diaries and newspaper clippings spanning her forty-year career. Additionally, they include plans and drawings from Feilman’s cadetship, postgraduate degree and early career as an architect. They offer a significant basis for further studies about her work and philosophies.

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander

1921-2021

Germany/Canada

Learning to juggle in life

Taken in 1989 in an orchard on her Vancouver property, the photo shows the landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander energetically juggling with a pair of apples. Oberlander, 68 years old, had just finished one of her famous collaborations with the architect Arthur Erickson: a project for which they were awarded the National Landscape Award [1]. Over the years, Oberlander had become a pioneer in her field. She had succeeded in giving landscape architecture a driving role within the construction of cities. At the time the image was taken, she was not only at the peak of her success, but already a grandmother of two and far from putting down her pen. The image could fall into a cliché: a woman in her Sunday dress, light-heartedly juggling a pair of apples. However, it is deliberately chosen to delineate the agency of Oberlander to the solitary act of her profession. Instead, it attempts to reveal the portrait of a woman that stood juggling many counteracting parts of her life.

Image Caption: Cornelia Hahn Oberlander juggling a pair of apples in her orchard in Vancouver, 1989.

Image Credits: Photo Kiku Hawkes.

One strand of her life was her escape from Nazi Germany at the age of seventeen. She went on to study at Smith College, and later at Harvard Design School, and left with great determination to succeed in her field. But when articulating her sentiments, she speaks of the struggle to assimilate to American society. Where the field of her interest was clear from the onset, nurtured by her mother’s profession as a horticulturist, her gravitation towards it was propelled by the unstoppable will power of an outsider to common social attitudes. Not only was she a woman, almost solitary in her profession, but a German Jew, ruptured from her previous cultural identity and made to continuously reflect on the status quo.

Just as she saw herself a stranger to her new life, she started to dwell on the issue of nature becoming ever stranger to city life. After graduating, she joined the office of the landscape architect Dan Kiley in Vermont, in whom she saw a mentor to her intrinsic awareness of the delicate state of the environment. It was Kiley who had told her to walk lightly in the woods, a comment which went on to reflect Oberlander’s advocacy for a humble relationship between nature and the urban fabric.

As a mother of three, it became far from easy to follow this mission. And even though she would set up her practice in their home in Vancouver and learn to tweak the system here and there – taking their children to the construction sites to play, for example – she speaks of much more than pragmatic solutions: ‘You had to have courage and self-confidence to last this type of life. The motto was: just keep on going.’ [2]

Returning to the image: the cliché is broken, and what we see, in fact, is a woman at work. As she threw one challenge up into the air, she had the another in the grip of her hand. It was in her capability to keep the strands of her life together that Oberlander demonstrates her agency: taking a stand on the challenges, tweaking the system, and making it work.

Sophia Trumpp

1 The Canadian Chancery in Washington, DC built 1983–90.

2 Hahn Oberlander, Cornelia. Interview. “Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Oral History Interview Transcript.” By Charles A. Birnbaum and Tom Fox. The Cultural Landscape Foundation Pioneers of American Landscape Design. 3–5 August 2008. Web. https://www.tclf.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Oberlander-Transcript.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2022.

Odilia Edith Suárez

1923-2006

Buenos Aires, Argentina

A Means of Change

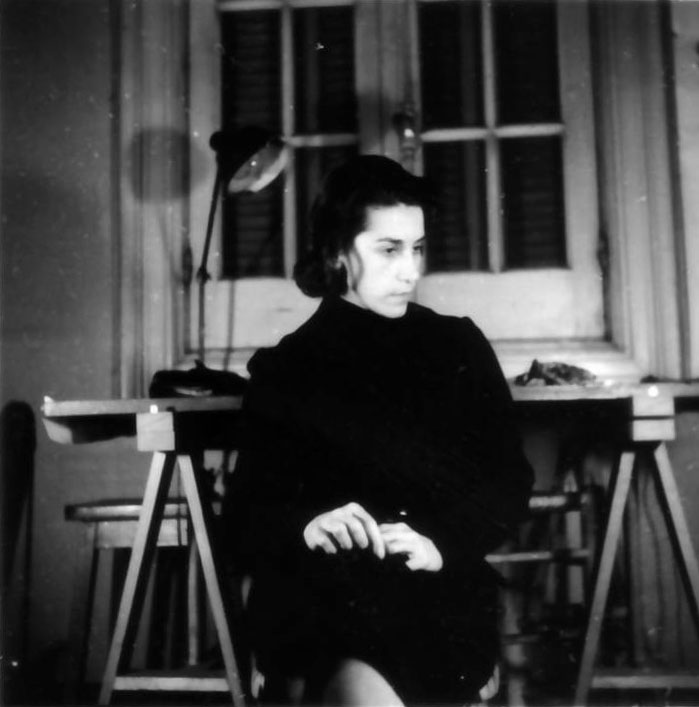

A contemplative look on her face, Odilia Edith Suárez is thinking of the living conditions of the citizens of Buenos Aires. Behind her, on her worktable, lie her plans for the city. Trying to improve people’s living conditions, Suarez was determined to defend the rights of a community in a political context which was limiting them.

Image Caption: Odilia Edith Suárez in Buenos Aires, circa 1940.

Image Credit: Unknown

Suarez started forming her understanding of urban design in the 1940s, during her studies at the College of architecture and city planning in Buenos Aires. During the last two years of her studies, she had started working under Antonio Bonet Castellana and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy, as part of the team studying the city plan of Buenos Aires. [1] Bonet Castellana and Ferrari Hardoy were among the founders of the collective of architects known as ‘Grupo Astral,’ a group active at the end of the 1930s which made a fundamental contribution to the debate on the renewal of Argentine architecture. Influenced by Le Corbusier, Grupo Austral promoted an idea of architecture as the ‘seed of the modern city,’ in which each building was seen as a form of individual expression and, at the same time, as part of a potential broader urban development that would contribute to improving people’s living conditions. [2] Being in contact with these ideas influenced Suarez, who would later publish her book, The Autonomy of the City of Buenos Aires: Reflections from a territorial point of view, in 1995.

Suarez, who in 1958 joined the board of directors of the Organisation of the Regulatory Plan of the City of Buenos Aires (OPRBA), believed that ‘urban planning must not only be strategic to satisfy the needs of its citizens, but must be dynamic to recognise that changes are, and have been, constant in an urban area.’ [3] She urged the expansion of the development of the southern neighbourhoods in order to relieve pressure on the more developed parts of the city. [4] She also recognised the importance of balancing the need to expand services in the central city with the demand for high-density housing. [5]

Furthermore, Suárez saw great significance in integrating the concerns of citizens into the planning process with the help of better communication. [6]

The twentieth century was a tumultuous period for Argentina, due to the changing leadership as a result of multiple coups. Beginning in the 1930s, the economy collapsed, resulting in a declining standard of living. [7] Juan Perón won the presidential election on a promise of higher wages and social security, but restricted political expression if it was not in his favour. [8] Perón initiated a project to provide housing for 50,000 people in the Bajo Belgrano neighbourhood, a poorly developed area of Buenos Aires, but the project was later abandoned. [9] Suarez, together with her husband, Eduardo Sarrailh, took the initiative to work on a proposal plan for the neighbourhood, trying to improve living conditions. In their joint practice, they also planned multiple civic centres, for which they received prizes on multiple occasions.

Suarez truly believed in defending the rights of the people in a political context which limited them.

Utilising the tools of urban planning and architecture, she aimed to bring direct changes to the life of ordinary people. Indeed, for Suarez, each building had the potential for broader urban development that would contribute to improving people’s living conditions.

Chloe Szwarc

1 Muxi. “Odilia Suárez 1923–2006.” un día | una arquitecta, 4 June 2015. Web. https://undiaunaarquitecta.wordpress.com/2015/06/04/odilia-suarez-1923-2006/. Accessed 15 April 2022.

2 “Grupo Austral.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grupo_Austral. Accessed 9 May 2022.

3 Ibid.

4 “Odilia Suárez.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odilia_Suárez. Accessed 15 April 2022.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 “Economic history of Argentina.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_history_of_Argentina. Accessed 9 May 2022.

8 “Argentina profile – Timeline.” BBC News. 5 Nov. 2019. Web. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-18712378. Accessed 9 May 2022. Wolfenden, Katherine J. “Perón and the People: Democracy and Authoritarianism in Juan Perón’s Argentina.” Inquiries Journal, vol. 5, no. 2, 2013. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/728/peron-and-the-people-democracy-and-authoritarianism-in-juan-perons-argentina. Accessed 9 May 2022.

9 “Bajo Belgrano.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bajo_Belgrano. Accessed 9 May 2022. “Villa Miseria.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_miseria. Accessed 9 May 2022.

Gira Sarabhai

1923-2021

India

Local craftsmanship in modernist eyes

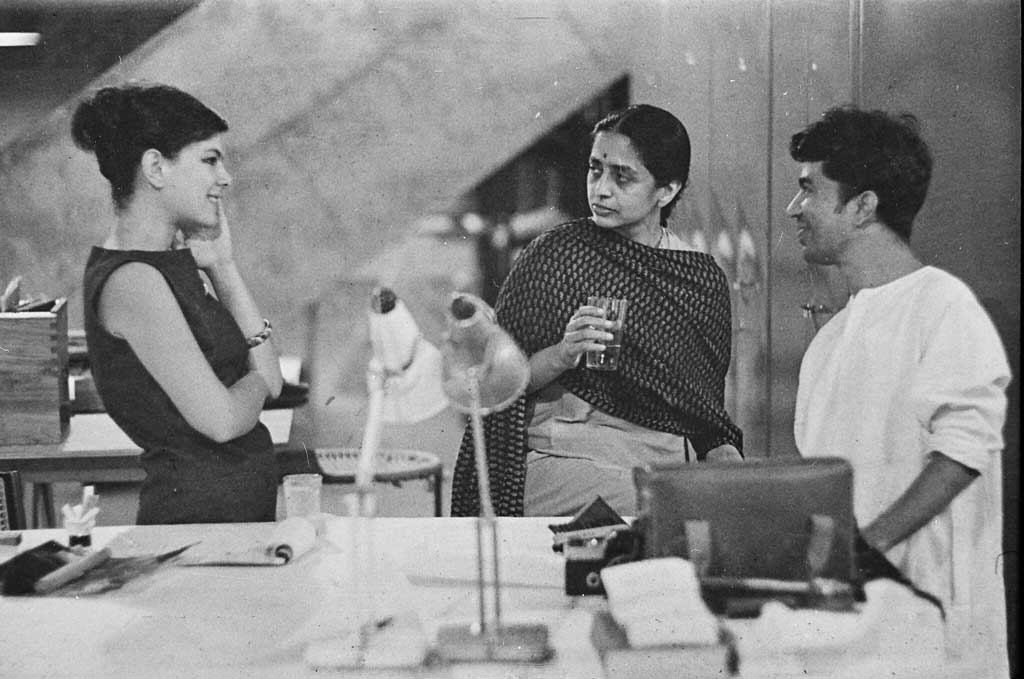

Standing in front of a desk scattered with paper and drawing utensils, Gira Sarabhai, with the American designer Deborah Sussman on the left, and the Indian artist Haku Shah on the right, are engaged in conversation. Both Sussman and Shah have a smile on their faces, visibly excited to meet one of the most important figures in establishing modernity in India during the twentieth century. With a serious, attentive look on her face, yet striking a relaxed pose, Sarabhai, coated in a traditional scarf, is listening.

Image Caption: Gira Sarabhai (in the middle) in conversation with the designer Deborah Sussman (to the left) and artist Haku Shah at the NID, Undated.

Image Credit: NID Archives.

Traditional fabrics, like the one she is wearing, have accompanied her for her whole life, not just as a matter of fashion, but as a sign of her identity. Her father, Ambalal Sarabhai, owned a big millinery company manufacturing traditional textiles in Ahmedabad. This resulted in all of his eight children being born into a family fortune. [1] With the funds available, and the family’s anthroposophical mindset, Sarabhai, like many of her siblings, made it her duty to bring welfare and prestige to her hometown, Ahmedabad. Sarabhai achieved this by means of architecture, education and labour. Through establishing a design school and a textile museum, and introducing many of her contemporaries and their manufacturers to her hometown, Sarabhai successfully put Ahmedabad on the global map of modernity, and brought new prosperity to the city.

Following the family’s move to New York in her teenage years, Sarabhai, together with her brother, Gautam, received an informal education from Frank Lloyd Wright, starting in 1947. Simultaneously, in 1949, Sarabhai and her brother founded the Calico Museum in Ahmedabad, showcasing their family’s heritage and traditional textiles. It was important to Sarabhai to bring together tradition and modernity. She commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright for the design of the museum. After the design fell through due to building restrictions, Sarabhai herself designed the Calico Dome outside the museum.

The geodesic dome, inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s designs [2], formerly embraced the shop and the display room for the museum it housed underneath – once again displaying the sought-after interconnection of the ‘western’ notion of modernity and local craftsmanship [3]. Twelve years later, in 1961, Sarabhai and her brother founded another institute in Ahmedabad, the NID (National Institute of Design). Assisted by advice from family friends like Ray and Charles Eames, the new school of design, craft and art was established to bring modernity, prestige and multiplicities of design to the city of Ahmedabad. This agency is also shown in several letters Sarabhai wrote to the Japanese designer Nakashimi, which detail her efforts to bring modern design and its production to India [4]. In 1972, Sarabhai resigned from the voluntary work at NID to focus all her work on the Calico Museum and its curation.

As a charismatic and strong individual from a privileged background, Sarabhai became a key figure in bringing modernity to India in the twentieth century. Sarabhai’s economic means, and therefore her social status, helped her not only to establish networks of designers, architects and artists, but also enabled her to keep her autonomy and power throughout the many political changes of the time.

Nils Grootenzerink

1 Although Sarabhai, as the youngest daughter born in 1923, was the only child to receive a formal education in the form of home-schooling, many of her siblings went on to receive academic degrees. Some, like her brother, Vikram, founded institutions in a plethora of fields, while others, like her sister, Mirdula, and aunt, Anasuya, engaged intensely in feminist and labour politics. See Spodek, Howard. “Local Meets Global: Establishing New Perspectives in Urban History – Lessons from Ahmedabad”. Journal of Urban History, vol. 39, no. 4, 2012: pp. 749-66; McGowan, Abigail. “Mothers and Godmothers of Crafts: Female Leadership and the Imagination of India as a Crafts Nation, 1947–67.” South Asia: Journal of South Asia Studies, vol. 44, no. 2, April 2021: pp. 282-97.

2 “Calico Dome.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calico_Dome. Accessed 27 May 2022.

3 Guth, Christine M. E. “Crafting Community: George Nakashima and Modern Design in India.” Journal of Design History, vol. 29, no. 4, June 2016: pp. 366-84.

Blanche Lemco Van Ginkel

1923 –

Canada

Designing From the Level of Needs

The importance and influence of Blanche Lemco van Ginkel on the world of architecture during the second half of the twentieth century is exemplified in this photograph. The young Lemco van Ginkel – about thirty at the time – had just graduated with a Master of City Planning degree from Harvard University, and was representing the Philadelphia CIAM group at CIAM 9 in 1953. Seen here with Le Corbusier in front of the Unité d’habitation in Marseille, the roof terrace of which she designed and conceptualised, Lemco van Ginkel seems to be explaining something, using hand gestures to make a point, while Le Corbusier, standing next to her, hands on hips, is listening. Perhaps this image is emblematic of the respect and appreciation Le Corbusier had for the young woman?

Image Caption: Blanche Lemco van Ginkel, Marseille, 1959.

Image Credit: Unknown

The design of the roof terrace of the Unité d’habitation in 1948 shows Lemco van Ginkel’s attitude towards architecture, urban planning and public space very early on in her career. Modelling the terrace after a town square with all its facilities, she focused on children, sport and leisure.

Together with her husband, Blanche Lemco van Ginkel founded an architectural and urban planning practice in 1957. Notably, they succeeded in saving Old Montreal, a historic neighbourhood that was scheduled for demolition to make room for the city’s urban development plans. Lemco van Ginkel managed to convince Montreal of the importance of historic building fabric for a city when contemporary discourse was still far removed from anything close to such an approach. Their success led to the implementation of urban planning as a profession in Canada, with Lemco van Ginkel herself working on the necessary legislation . [1]

As an educator, Lemco van Ginkel taught at various well-known institutions, including McGill University, the University of Philadelphia, Harvard and the Université de Montréal. Far from merely teaching, Lemco van Ginkel also was developing her own courses on urban design, still an emerging field in the 1960s and 1970s, and was sculpting and influencing its role in architecture. Being a new field of work and study, her hope was for urban design to be a more inclusive environment for women than architecture. ‘Architecture is a cultural pursuit and those who practice it, or are allowed to practice it, reflect our culture, our mores, our attitudes, in Canada as elsewhere,’ she wrote in 1991. [2]

In 1977, Blanche Lemco van Ginkel became the first woman to be appointed Dean of Architecture in North America at the University of Toronto. [3] Lemco van Ginkel broke ground for women in many fields, mostly through pushing the limits of what was perceived as possible for women in educational and governmental institutions. She also tried to shed light on the achievements of Canadian women in architecture through publishing articles, curating exhibitions and sharing her own experience publicly. [4]

The emergence of urban planning as a profession was greatly facilitated by the work of Lemco van Ginkel. She approached urban planning not from an authoritative top-down way of thinking, but from the level of needs and from a more human scale. In this way, she displayed far more understanding and flexibility than most of her peers in the 1970s. At the same time, she also valued the meaning and importance of existing urban structures, perhaps in reference to the walkable city, a concept which was largely destroyed in North America with the emergence of the automobile, and also the need for a collective memory of a place.

Max Schubert

1 The first Quebec Provincial Planning Commission, between 1963 and 1967.

2 Lemco van Ginkel, Blanche. “Slowly and Surely (and Somewhat Painfully): More or Less the History of Women in Architecture in Canada.” SSAC Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 1, 1992: pp. 5-11.

3 She served in this capacity for a five-year term, from 1977 to 1985.

4 Consider, for example, an exhibition in 1986: ‘For the Record: Ontario Women Graduates in Architecture, 1920–60,’ University of Toronto.

Vittoria Calzolari

1924-2017

Italy

The woman who created the idea of landscape [1]

Vittoria Calzolari is pictured carefully rearranging the plants in her home, as was her wont, an echo of her career working to provide green spaces for cities. The photo is almost a manifesto of concealment; a human behind the non-human. Known as a very modest woman, Calzolari was always hidden behind the work she created. Almost no other photograph of her is to be found, even though she held public office for many years, and was an active and engaged architect, urbanist and professor. [2]

Image Caption: Image Caption: Vittoria Calzolari carefully rearranging the plants in the garden, Isola d’Elba, 2007.

Image Credit: Unknown

Calzolari’s agency expanded from education to the social, and from public engagement to legislation. This interdisciplinary impact is reflected in the strong interlocking of theory and practice in her oeuvre, and in her conception of landscape. Calzolari defined a new discipline that she named ‘paesistica.’ [3] Paesistica understands the landscape as continuously evolving, taking the historical process of its creation into account. [4] It invites an interdisciplinary approach, looking at the landscape though different eyes.

Water always played an important role for Calzolari, as both a resource and an indispensable system for the planning and interpretation of territorial landscape. [5] Her first encounter with water as a territorial and city-boundary element was in her childhood in Mogadiscio, Somalia, where her father worked on the construction of the port. [6]

One of Calzolari’s most representative works is her project for the park of the Via Appia. [7] In this project, the two spheres of landscape design and preservation are strongly linked to one another. The continuity of the great dimensions [8] of the park had been destroyed over the centuries. [9]

The objective of the project was therefore to recreate the formal unity of the park, restoring the sense of grandiosity and reevoking the memories associated with it.

Together with her husband, [10] Calzolari wrote a study, Il Verde per la città. [11] This later supported legislators in the formulation of a decree [12] on urban standards that still, today, determines the amount of green space that every Italian citizen must have access to in the city.

Even though Calzolari’s projects, publications and roles [13] are very different from one another, a golden thread can clearly be identified: the importance of water and green spaces, and a sensibility to historical, artistic and environmental patrimony, as well as her intellectual and political commitment.

Margherita Chiozzi

1 Erbani, Francesco. “La signora che creò l‘idea di paesaggio.” La Repubblica. 4 December 2012. https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2012/12/04/la-signora-che-creo-idea-di-paesaggio.html. Accessed 20 July 2022.

2 Calzolari was a professor at the Universities of Rome and Naples.

3 This term differs from the often used ‘paesaggistica.’ Both terms are translated the same way in English, to mean landscaping or landscape design.

4 Mora, Alfonso Álvarez, ed. Paesistica = Paisaje, Vittoria Calzolari, Paesistica = Paisaje. Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid, 2012. 17-20.

5 Ibid.: 26.

6 Ibid.: 36.

7 This project was initiated in 1973 by the non-profit organisation Italia Nostra, of which Vittoria Calzolari was a member for many years, dedicated to the protection and promotion of the country’s historical, artistic and environmental patrimony. Calzolari strongly shared with Italia Nostra the approach to urban planning focusing on the preservation of historic architecture.

8 3000 hectares.

9 The park was decimated through the addition of fences, construction and traffic. Mora, ed. Paesistica = Paisaje, Vittoria Calzolari, Paesistica = Paisaje, 183-207.

10 She met her husband while working on one of her first projects in the context of the national competition for economic and social housing in Naples.

11 Calzolari, Vittoria, and Mario Ghio. Il Verde per la città. De Luca Editore, 1961. The book was commissioned for the Olympics in Rome.

12 Decreto Ministeriale n. 1444, 2 April 1968.

13 Calzolari was a professor, architect, urbanist and public officer.

Françoise Choay

1925-

France

Rewriting the Urbanist’s Archaeology

This photograph, taken during the filming of a documentary on the legacy of Georges-Eugène Haussmann, [1] shows the design historian and art and architecture critic Françoise Choay walking the streets of Paris. In this film, as well as in the photograph, what becomes evident is Choay’s very humanistic approach to urbanism and her sharp, critical mind. What one can also sense from the photograph is Choay’s visceral need to visit places, to walk them and experience them, to go to the source and explore the essence of the subject in order to sense proportions and space. She also highlighted the need to have a critical eye in the lectures that she delivered from 1966 onwards at the University of La Cambre in Brussels and the University of Vincennes in Paris, [2] as well as universities in the United States and Italy. In her classes, she encouraged students to look critically at the purely functionalist conception of urban design, and to question the tasks of the designer by going on site and experiencing it.

Image Caption: Françoise Choay walking in Paris, circa 2013.

Image Credit: Still from Jean-François Dars and Anne Papillault (dir.).

Choay does not criticise urban planning per se, but rather the theories underlying urbanism and heritage. She does so through her publications, notably Urbanisme, utopies et réalités. Une anthologie (1965), [3] a book that exemplifies her critical examination of thoughts in the discourse of urban design. The book provides a concise summary of urbanism-related ideas from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Simultaneously, Choay analyses the urbanisation of the twentieth century via the works of thirty-seven different authors, and identifies purported new planning strategies as models. The book stands out for its extraordinarily manifesto-like character. [4]

Choay’s wide-ranging interests and engagement were also evident in her academic career, which began with her initial studies in philosophy, before turning to aesthetics, architecture and, finally, urban planning. Choay was born in Paris in March 1925. Brought up in a bourgeois, secular and republican Judaic and Alsatian Protestant family, she acted in the Resistance by transmitting news next to her philosophy studies, and having an enormous interest in the people and situations around her. Choay’s foundation and convictions were laid and strengthened early in her life. [5] After she finished her studies, she dedicated herself to art and architecture criticism. What marked an interdisciplinary shift in her career was her 1965 article on designer Jean Prouvé’s Maison des Jours Meilleurs (1956).

Choay visited Prouvé’s prototype house, built as a response to the government being forced to commit to funding a shelter after many homeless people froze to death in the winter of 1954. Following the publication of her review in a French news magazine, France Observateur, she wrote numerous other articles, including a report on the grands ensembles, in which Choay was one of the first to criticise the French state’s urban planning response to the housing shortage after World War II.

Choay’s experience in journalism influenced her career very positively, sharpening her sense of observation, critical thinking and ability to focus on the essentials. These characteristics informed both her academic writing and her work as a lecturer decisively, and thus contributed significantly to her success.

Julia Tanner

1 Histoires courtes DarsPapillault. POURQUOI HAUSSMANN Par Françoise Choay. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/328801564. Accessed 20 April 2022.

2 Frey, Katia, and Eliana Perotti, eds. Frauen Blicken Auf Die Stadt Architektinnen, Planerinnen, Reformerinnen. Reimer, 2019.

3 Choay, Françoise. Das Architektonische Erbe, Eine Allegorie: Geschichte Und Theorie Der Baudenkmale. Trans. Christian Voigt. Vieweg, 1997.

4 Choay, Françoise. Interview. “On the Disaster of Amnesia. An Interview with Françoise Choay.” By Lionel Devlieger. ARCHIS, vol. 4, 2003: pp. 26-31.

5 Paquot, Thierry. “L’invitée: Francoise Choay.” Urbanisme, vol. 278, November–December 1994: pp. 5-12.

Gae Aulenti

1927-2012

Italy

Never Look Back

The building site of the Gare D’Orsay, with its brutalist concrete cores, metalwork studs and dim light, forms the background of this scene, otherwise showing two female figures fiercely walking ahead, careless of the objective of the camera. They are the architect Gae Aulenti and her beloved granddaughter, Nina. Aulenti is wearing a long black coat and a red site helmet, matching the all-red outfit of the little girl, holding onto her grandmother’s hand as if to find a sense of security in such an overwhelming space.

The refurbishment of the former Paris railway station into the Musée D’Orsay by Italian architect Gae Aulenti in the 1980s was one of the first examples of European reconversion of a disused industrial structure into a cultural space. [1] With its collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art, this revolutionary project added one more cultural powerhouse to the city of Paris, representing a turning point in the career of Aulenti, who was 58 years old at the time.

Image Caption: Gae Aulenti and Nina Artioli on the building site of the Museè D’Orsay, Paris, 1984.

Image Credits: Archivio Gae Aulenti.

Aulenti’s passion for architecture started at an early age. Her ambition to pursue a career, in opposition to the traditional role assigned to women in her family, led her to enrol at the Politecnico di Milano, from which she graduated in 1953. [2] After a short-lived marriage, her daughter Giovanna was born, and more or less the same year, Aulenti set up her own architectural practice from home, working alone on a number of competitions and interior refurbishments. [3]

What laid the foundation of Aulenti’s later success were the first ten years of her professional career, spent working as a graphic designer for the architectural magazine Casabella-Continuità. [4] Surrounded by influential intellectuals and visionary architects, Aulenti developed her professional agenda while becoming an active force in reimagining a new world for post-war Italy, one where tradition met technology in a harmonious balance. Aulenti believed that architecture is always a collective gesture, never an individual one, something which, therefore, should benefit the community as a whole; this belief is visible in all her projects, from everyday furniture to buildings. [5]

The success of the Musée D’Orsay led Aulenti to the political decision of mainly engaging in the construction of public cultural projects, making her agency tangible in many cities around the globe. Aulenti was ahead of her time in seeing the potential of transforming old industrial ruins into spaces for cultural exchange, where past and future could walk hand in hand towards a more inclusive society.

‘Architecture is a male profession, but I never took notice,’ she once said, crystallising in a few words her indifference towards sexism and her attitude as a professional. [6] One of the first Italian woman architects to succeed at all scales of the project, she made the dream of becoming one possible for many, including Nina.

Michela Bonomo

1 Aulenti teamed up with the architect Italo Rota and the lighting architects Piero Castiglioni and Richard Pedruzzi, winning the competition for the Museè D’Orsay. The project started in 1980, and was completed in 1986. It is today one of the most visited museums in the world.

2 Aulenti was one of two women graduating in a class of twenty men.

3 Gae Aulenti set up her own studio in 1955, the same year she gave birth to her only daughter after separating from her husband, Francesco Buzzi. The architect’s first built work was a private house with adjacent stables in San Siro (Milan), commissioned by the Cumani family and completed in 1956.

4 The editorial board of Casabella-Continuità was directed by Ernesto Nathan Rogers between the years 1955 and 1965. Alongside working at the magazine, Gae Aulenti became a teaching assistant at the Politecnico di Milano for Ernesto Nathan Rogers, and at IUAV for Giuseppe Samonà.

5 Furniture design was a common entry point for female architects to break into the profession. Among the most famous furniture design projects are: Locus Solus for Poltronova (1964), Pipistrello table lamp for Matrinelli Luce (1965), Jumbo marble table for Knoll (1965), and Oracolo and Mezzo Oracolo for Artemide (1968). Appropriating the motto revived by Ernesto Nathan Rogers that a ‘good architect should be able to design from the spoon to the city,’ Aulenti’s office realised more than 200 buildings, of which the following are the most famous: Olivetti Store in Paris (1966), Fiat Showroom in Genoa (1968), Installation at the National Modern Art Museum at Centre Pompidou in Paris (1985), Renovation of Palazzo Grassi in Venice (1986), Italian Pavilion at Expo in Seville (1992), Plan for the Italian Cultural institute in Tokyo (1998), Renovation of Scuderie Papali in Rome (2000), and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco (2003).

6 Aulenti has been considered by some a feminist with extreme views. She believed that discussing the gender of an architect within the profession would reinforce the binary status quo, which identified women as experts in interior decoration and furniture, and put men more in charge of the actual architecture of the building, thus undermining the role of women in the profession.

Phyllis Lambert

1927 –

Canada

The Woman who Brought Architecture Closer to the People

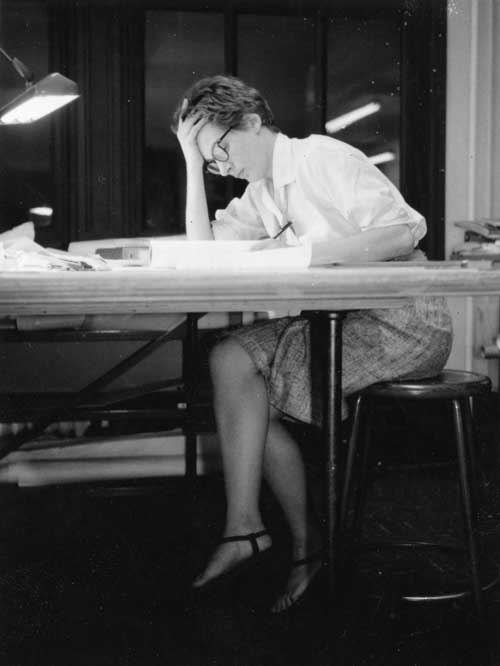

It is 1959, and a young Phyllis Lambert is sitting at her desk in Mies van der Rohe’s Studio in Chicago. She is wearing a skirt, legs crossed, her head resting in her hands and looking down at the project on the table, focused and dedicated. This photograph shows an early moment in Lambert’s extensive career as an artist, architect, activist, museum director, and protagonist working for the transformation of the environment in many senses. Moreover, in her career Lambert rarely appeared in the way she is shown in the picture. She is usually seen occupying much less traditionally-feminine postures, not sitting at a desk working on projects, but rather in action, following her agenda of connecting society with the architecture of Canada.

Image Caption: Phyllis Lambert at her drafting table in Mies van der Rohe’s office, Chicago, 1959.

Image Credit: Photo by Ed Duckett, Fonds Phyllis Lambert, Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), Montreal.

Lambert was always very keen on her independence, especially from her family. She had her ideas, and worked hard to implement her visions. She grew up in a rather influential and wealthy family in Montreal. She first left her home city to study at Vassar College, New York, where she completed her bachelor’s degree in 1948. Only a year later, she went abroad to France, and married Jean Lambert. The marriage for her was less a way of showing her love for him than to separate herself further from her family, and gain distance from the family name. The marriage did not last too long, and the couple divorced in 1954. In the same year, she returned to the USA, determined to help build a New York headquarters for the Seagram Company Ltd, owned by her father, Samuel Bronfman. Indeed, it was Lambert’s influence that led to the construction of the Seagram building by Mies van der Rohe, a design which would forever change the face of New York. Her work on the project was also the beginning of her close relationship with Mies.

Early on, Lambert started focusing on urban and social issues rather than working on projects. She collected parts of cities in the shape of photographs, plans and experiences. Those mementoes were important to her because of her interest in the history of cities, especially when it came to Montreal. As a leader in social issues of urban conservation, she founded Heritage Montreal, a non-profit organisation dedicated to protecting and promoting the history and architecture of Montreal and its metropolitan area. The idea was sparked as a countermovement against the demolition of great parts of the cities by the government.

Furthermore, Lambert established the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in 1979 as a way of bringing her passion for architecture and the history of Montreal closer to society. The building of the CCA, completed in 1989, contains a library, museum and a big public garden. Like Heritage Montreal, the CCA symbolises Lambert’s agency in bringing architectural and urban knowledge closer to society and the people. Her agency, therefore, can be described as a counter-agency of the government, with both Heritage Montreal and the CCA.

As a protagonist working for the promotion and preservation of the built environment, Lambert adopts a position for the people and the city with a very personal approach. Her family and upbringing might have helped her to get to where she is now, but she used the influential power that was given to her to give back to the development of her hometown, and create a civic space that really gives something back to the people of Montreal. She has come a long way from where she started, but her dedication to architecture, cities and her thinking remains.

Sophie Keller

Denise Scott Brown

1931-

South Africa/USA

Her Visual Sharpness

29-year-old Denise Scott Brown takes a self-portrait in the mirror. [1] The scene shows frames and mirrors. On the left side, there are multiple blurred reflections visible. Standing in front of the mirror, Scott Brown does not look directly into the beholder’s eyes, but looks straight into her camera, focusing a point on the mirror. Her focus in the middle of the picture becomes sharp. Scott Brown’s agency lies in her different way of looking at things, an innovative gaze on the city fabric. With her book, Learning from Las Vegas, published in 1972 and written with Robert Venturi and Steve Izenour, she had created a new basis for the city’s investigation.

Image Caption: 29 years old Denise Scott Brown takes a self-portrait in the mirror.

Image Credit: Hilar Stadler and Martino Stierli (Eds.) Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2008.

When she gets an idea into her head, she focuses and does everything to implement it. One focus is being in the vanguard of things. Indeed, Scott Brown always thinks about urban improvements, how people are going to live and interact in the future. In her view, architecture is not just about building void vessels. Scott Brown’s solution is not to build new buildings in response to an urban problem and hope that this will solve it: there is so much more behind her approach. Her ability to look beyond present configurations makes her architectural and urban approach remarkable. [2]

Her South African roots play an important role in connection with her gaze. In interviews, she often describes how the culture and social segregation in Johannesburg influenced everyday life. She learned to develop her creativity through the landscape. As such, it was important to carefully observe the environment. When she investigated Las Vegas, it was precisely this practice that helped her further. [3]

Scott Brown analyses the city through taking photographs, ordering them in series to understand and visualise her ideas. But even this meticulous approach she deems not sufficient. ‘You can’t just look at pictures and books; you have to go and look at the real thing.’ [4]

Through her travels across Europe, she gathered experience for expanding her knowledge of urban design. Her broad horizon is mirrored in the elaborated city patterns. Colourfully highlighted, the mapping method of land use shows, for example, where commercial and residential floors are situated. It is a basis for investigating complexities and their interplay. As an important writer, educator and lecturer at many universities like Pennsylvania and Harvard, she is able to translate her approach into a visual language. [5]

To conclude, her agency lies in the way she looks at cities. Compared to other architects, she looks at banalities that others neglect or ignore. An example of this is the mapping method. Many students and co-workers do not understand the approach, because it may seem too abstract at first glance. Nevertheless, she tries to sensitise the people to sharpen their gaze. Only a sharp gaze leads to innovation in the end.

Catia Marcotulio

1 Stadler, Hilar, et al. Las Vegas Studio: Images from the Archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Zürich, 2008. 111.

2 EPFL. “Denise Scott Brown.” 21 September 2011. https://www.epfl.ch/campus/art-culture/museum-exhibitions/archizoom/denise-brown/. Accessed 20 July 2022.

3 dérive Stadtforschung. Denise Scott-Brown: An African Perspective. Interviewed by Jochen Becker (metroZones). Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/312749292. Accessed 20 July 2022.

4 Scott Brown, Denise. Interview. “Denise Scott Brown on the Signs and Symbols for Living.” By Peter Barberie. Aperture. 26 March 2020. https://aperture.org/editorial/denise-scott-brown-las-vegas/. Accessed 20 July 2022.

5 EPFL, “Denise Scott Brown.”

Iris Dullin-Grund

1933 –

GDR

Making Room for a Washing Machine

Iris Dullin-Grund, wearing a light-coloured dress, is standing beside a huge model of the GDR City of Neubrandenburg. She leans forward while pointing at the new suburban area of Datzeberg. The huge model almost fills the whole room, dividing the chief city architect from her audience – four men sitting, partly leaning forward, apparently listening to the architect with unwavering concentration.

Image Caption: Neubrandenburg, around 1975: Iris Dullin-Grund explaining the model of a new residential area of Neubrandenburg, the Datzeberg.

Image Credit: Photo Hans Wotin.

The photo was taken around 1975 in Dullin-Grund’s architectural office in Neubrandenburg. [1] Since 1970, she was chief city architect, the highest position an architect could achieve in the GDR. [2] When she started to get involved with city planning, the construction of new suburban areas in the East had already begun, and the plan was to continue in the same direction. [3] Dullin-Grund saw this expansion as highly problematic: ‘In the end, next to the historic centre, there would be a gigantic, undifferentiated new housing development without orientation, without a centre, without character.’ [4]

Therefore, Dullin-Grund proposed another approach: her development plan envisioned the historical city centre as heart of the expanding city, while the residential areas would settle within sight on the surrounding plateaus. Instead of a uniform repetitive large housing area, each new residential neighbourhood would be given its own unique character and distinctive views. Instead of levelling the land, she worked along the contour lines, (Dullin-Grund 89) giving the buildings their curved shape, which can be seen in the photo, where she is perhaps pitching her proposal to colleagues or the government.

In her city planning, Dullin-Grund paid great attention to microplanning in urban design, which primarily benefited working women. For example, the workplaces were to be located close to the housing estates so that women could ride their bicycles to work. On their way to school, children would not encounter busy roads, and there would be kindergartens en route so that older children could take their younger siblings with them, further unburdening their mothers. [5]

Dullin-Grund’s agenda was to make life easier for women balancing the roles of housewife and employee, and she thought through even the smallest details; for example, she was committed to making space available for washing machines in the scant rooms of the slab buildings. [6]

Iris Dullin-Grund had to defend each of her ideas and justify her decisions, because as a young woman she was not taken as seriously as her male colleagues. Her agency was to learn what arguments would win over the government and her primarily male colleagues, to be able to pursue her real interests: the greatest quality of living possible for the residents, with a special emphasis on women.

Elena Rieger

1 Dullin-Grund, Iris. Geschichte einer Architektin: Visionen und Wirklichkeit. Mein Buch, 2004: 108.

2 Petra Lohmann, ‘Stadtarchitektin im Sozialismus: Iris Dullin-Grund’ in Frau Architekt: seit mehr als 100 Jahren: Frauen im Architekturberuf : over 100 years of women in architecture. Ed. Christina Budde et al. (Tübingen: Wasmuth, 2017) 197.

3 She was appointed to rebuild and expand the city of Neubrandenburg, 80% of which had been destroyed during World War II, and which was to grow by at least 50% in the coming decades. Krahn, Franz. “Ein Bezirk Mit Zwei Hauptstädten?” Neues Deutschland. 25 August 1966; Lohmann, Petra. “The Architect Iris Dullin-Grund in Films of divided Germany.” Ideological Equals: Women Architects in Socialist Europe 1945-1989. Eds. Mariann Simon and Mary Pepchinski. Routledge, 2017. 172–73, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315587776.

4 Dullin-Grund, Iris. Geschichte einer Architektin: Visionen und Wirklichkeit. Mein Buch, 2004: 88

5 Iris Dullin-Grund: PLATTENKÖPFE – Iris Dullin-Grund, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UezHw_nGvlA 9:30 to 10:15.

6 By that time, washing machines were not standard in GDR households, but Dullin-Grund saw the potential that they eventually would be. (Dullin-Grund 90–91)

Kodirova Tulkinoy Fazildjanovna

(Кадырова Тулкиной Фазилджановна)

1935-2014

Uzbekistan

A woman’s agency in the USSR:

Kodirova Tulkinoy Fazildjanovna and her ambitions for a contemporary Uzbekistan.

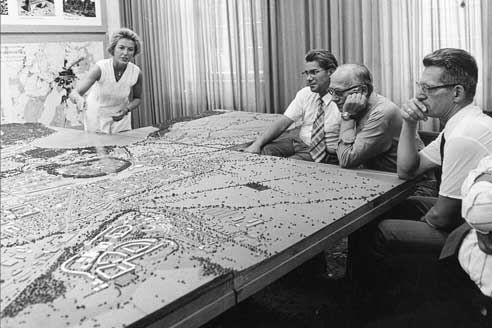

Kodirova Tulkinoy Fazildjanovna stands in a position of authority, navigating her micro and macro impacts on the city of Tashkent, Uzbekistan. In the foreground is a new proposal for a civic building; in the background, a city-scale urban plan for Tashkent, suggesting a vision for the future. Around Fazildjanovna stand three unidentified men, likely fellow government officials who worked alongside her. Yet in this seemingly staged image – a common technique used in the USSR for propaganda – she occupies the central position. [1]

Image Caption: Kodirova Tulkinoy Fazildjanovna (1935-2014) during a planning meeting alongside three unidentified men in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. They stand amongst micro-scale urban developments and a macro-scale urban plan for the city.

Image Credit: ‘Тулкиной Кадырова. Letters from Tashkent’, 5 Dec. 2016.

Fazildjanovna’s authority translated into agency, allowing her to determine the future of her home city. Fazildjanovna was an Uzbek architect, educator and planner. Her position as a woman in the USSR afforded her professional opportunities beyond what other women experienced at the time. She took full advantage, and navigated the communist system to her benefit in order to realise a contemporary urbanism for Tashkent.

Fazildjanovna was born in the former USSR state of Uzbekistan on 27 July 1935. She completed her architectural studies at the Central Asian Polytechnic Institute, and soon after began climbing the ranks of the Institute of Culture. [2] Following this, she was elected – democratically or not – to the Supreme Soviet. [3] The communist ideology of the USSR believed all civilians to be equal, seemingly making Fazildjanovna equal to her male colleagues. [4] She held high positions in the government, which was unheard of in other countries at the time. Despite her presence, the professional realm was still heavily male dominated. As such, perhaps it is reasonable to assume Fazildjanovna was determined to succeed no matter what. By 1995, she became the deputy director-general for Construction in Uzbekistan.

These high positions granted her the ability to develop her vision for Tashkent. Her vision focused on modernising the city, using a meaningful understanding of the past to inform the future. On the micro level, she designed, wrote [5] and taught [6], focusing on developments within Tashkent at the time.

Her continual efforts over her career to better the city accumulated into large-scale changes. In her books, she wrote in great depth about the history of her country, outside of the USSR’s hold. Today, her books remain significant references for architectural history in Uzbekistan [7].

On the macro level, Fazildjanovna had a large vision for architecture and urban planning beyond her governmental roles. In 1980, she founded the Union for Architects of Uzbekistan. Her ambition in creating such a union shows us how much she was committed to sharing her agency with others. Though the Union no longer exists, it was still a highly significant act. Fazildjanovna used her agency to mobilise other architects and planners to continue the work that she started. She understood that she could achieve more through community and collaboration than if she worked alone.

Kodirova Tulkinoy Fazildjanovna’s career shows us that agency is relative. As a woman in the USSR, she was simultaneously liberated by policy but bound by bureaucracy. How we understand her urban agency cannot be removed from the mutually-beneficial relationship she maintained with the political system within which she operated. For Fazildjanovna, she understood her context, acted upon given opportunities and manifested an agency placing her in a central position to decide Tashkent’s urban future.

Sonya Falkovskaia

1 Such photos were used by the communist regime to control the image of the USSR for the people. Women were often placed alongside men, appearing equal, as this aligned with their vision for society. However, women were not equal, and were instead used to perpetuate falsehoods and strengthen the grasp of the regime over the people. Macdonald, Fiona. “The early Soviet images that foreshadowed fake news.” BBC News, 10 Nov. 2017. Web. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20171110-the-early-soviet-images-that-foreshadowed-fake-news. Accessed 20 July 2022.

2 The Institute of Culture oversaw the organisation of culture and leisure activities within the USSR. “Palace of Culture.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palace_of_Culture. Accessed 20 July 2022.

3 The Supreme Soviet was a legislative body, and the only one to approve constitutional changes. This gave Fazildjanovna a significant appearance of power; in reality, it is unclear how much agency this legislative body had within the superstructure of the USSR at the time. She was one of 300,000 people elected, but the selection process is also unclear. The first certified free elections did not take place until the late 1980s, so perhaps it is reasonable to assume that, as Fazildjanovna was already esteemed within her field before the nomination, she knew the right people and understood how to work the system. “Supreme Soviet.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supreme_Soviet. Accessed 20 July 2022.

4 This is not to say that women were truly equal to men, as they still had responsibility for childcare and domestic life; however, there were more opportunities than elsewhere for them to have higher positions of power, like Fazildjanovna. In the USSR, women were given equal rights to men in 1917. By comparison, the UK only granted this in 1928. “Women’s Suffrage.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_suffrage. Accessed 20 July 2022.

5 During her lifetime, she published twelve works in twenty-nine publications between 1965 and 1998. “Кадырова, Т. Ф (Тулкиной Фазылджановна).” OCLC WorldCat Identities, n.d. Web. https://worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n82131772/. Accessed 20 July 2022.

6 She became a professor at the Tashkent Institute for Architecture and Construction (TASI), where she taught until she died in 2014. Lavrova, Violetta. “Тулкиной Кадырова.” Письма о Ташкенте, 5 Dec. 2016. https://mytashkent.uz/2016/12/05/tulkinoj-kadyrova/. Accessed 20 July 2022.

7 They remain a comprehensive first-hand source of information on Tashkent and Uzbekistan architectural history, written originally in Russian.

Saskia Sassen

1947-

USA

A global urban gaze

‘I am nomadic… home is the place where I can work.’ [1]

This photograph portrays sociologist Saskia Sassen sitting in her apartment in New York, looking at the city through the window. Illustrating Sassen’s cosmopolitan vision of the world, the image shows her looking directly at a global city, the main subject of her research. In the background we can see her desk, with a few books, certainly some of her own writings, a clock that looks like a tower and that seems to be controlling the space, and a green teapot. The desk behind her is part of her workplace, where her books and articles are written: the place from which her agency emerges. A citizen of the world, however, her agency is not bound, physically or metaphorically, to the idea of the home. Sassen’s work has a clear influence on her lifestyle, and vice versa, as her childhood and education were also very international. [2] Even her clothes seem to be a kind of Japanese-style silk ensemble, perhaps a souvenir from one of her many trips.

Image Caption: Saskia Sassen, New York City, 12th December 2016.

Image Credits: Photo Steve Pyke.

Sassen does not build, or design, the city, but she investigates its future inner workings. In the picture, she has adopted a very laid-back position, casting a calm gaze at that buzzing global city, almost suggesting her secure knowledge of it. Her passive pose shows this more passive agency; not an agency on the city itself, but its analysis. It is a passive agency in the sense that it is observational, descriptive and analytical; it is not a direct action, but one that has a clear influence on, and consequences for, the way cities and their globalisation are perceived and conceived, as she aims to find the link between the social, economic and spatial aspect of New York.

Her first of eight major works, entitled The Global City: New York, Tokyo and London, [3] published in 1991, set the tone of her research. It analyses how a growing global economy is highly linked with territorial and urban agency. She argues that a global city and geographical centrality is transformed by global systems like cross-border dynamics, transnational networks and multinational firms. With this thesis, she triggered the popular idea that globalisation goes beyond geography. [4] The academic journal Development and Change commented that it ‘should be read not only by… economists but also by urban geographers, sociologists, and planners.’ [5]

Consequently, in 1995 she was invited to the ANYwise conference in Seoul, South Korea, with the theme of ‘Urban Continuity and Transformation; Reconfiguring Centrality.’ There, she articulated the socio-economic and spatial idea of centrality. She focused on the future forms of centrality and explained spatial pluricentralities in terms of geographic dispersal and globalisation. Until 1999, she participated at these conferences, which aimed to link the discipline with cross-cultural knowledge and dialogue with a variety of actors, five times. [6] She was, thereby, part of a turning point in urbanism and city planning.

Sassen’s analytical view of the city’s global aspects influences not only how she conceives the world, but also the vision of others, namely through her publications, conferences and teaching, which in turn re-shape the cities themselves.

Julie Theythaz

1 Barbour, Celia. “The guilt of Having a Good Thing.” The New York Times. 23 September 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/23/realestate/23habi.html. Accessed 24 April 2022.