Underground City Montreal

A sheltered passageway between business and society

A sheltered passageway between business and society

Used by more than 500,000 pedestrians a day, the Underground City Montreal is one of the world’s biggest public excavated connection infrastructures. This indoor public walkway network is 32 kilometres in length, covering an area of 12 square kilometres in the city’s downtown.

While in many cities separate passageways protect pedestrians from traffic, the Underground City Montreal is primarily intended as refuge from the extreme weather conditions of Canadian winters. The sheltered walkway network connects offices, retail and housing units on the surface with the metro system below, extending the commercial functions onto several underground levels.

Originally envisioned by urbanist Vincent Ponte, the pedestrian network was begun in 1962 and has continued to grow. Rather than following a predetermined masterplan, its organic development was negotiated between various private ground owners and the city’s government. This brings up questions of ownership and side-by-side governance of this common space.

Accessibility problems are solved by linking the opening hours of the underground city to the ones of the metro system. The most contested issue, however, is spatial control. Since the underground city is economically driven, concentrated on retail and business, the majority of owners and visitors are middle-class, making it unwelcome to lower-income segments. Independently monitored by security agencies with closed circuit surveillance systems, employed at the discretion of each proprietor, the underground is subject to uncoordinated forms of spatial control. This raises controversial choices facing proprietors and tenants: who should be allowed in or kept out?

In order to be considered an urban common, Underground City Montreal must address how its regulation and expansion could include a bigger diversity of and create more fluid transitions to the outside public spaces, leading to a higher diversity of users and welcoming all segments of society.

El-Geneidy, Ahmed, et al. ‘Montréal’s Roots: Exploring the Growth of Montréal-Trust Indoor City.‘ Journal of Transport and Land Use. Volume 4, no. 2, 2011, pp. 33-46.

Zacharias, John. ‘Modeling Pedestrian Dynamics in Montreal’s Underground City.‘ Journal of Transportation and Engineering, 2000, pp.405-412

Bélanger, Pierre. ‘Underground landscape: The urbanism and infrastructure of Toronto’s downtown pedestrian network.‘ Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology. Volume 22, Issue 3, May 2007, pp.272-292

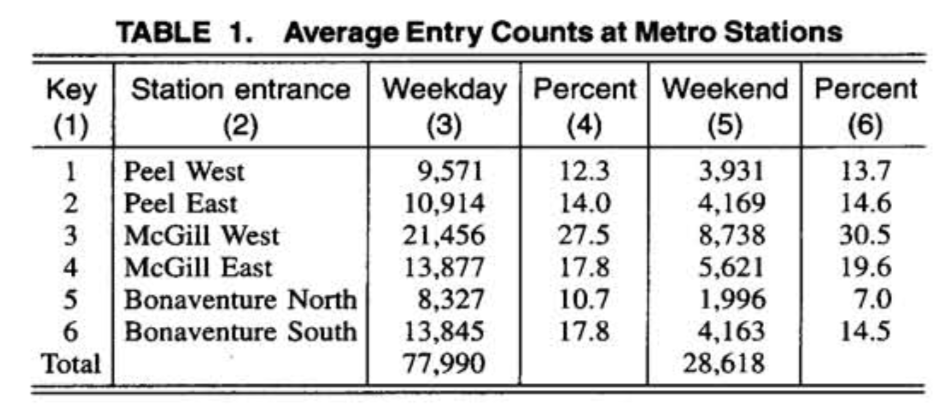

Image1 –

Times coverage map of the underground network during weekdays, and evenings and weekends.

(Bélanger 2007, p. 285)

Image 2 –

View through a retail corridor under the place Ville Marie.

Image 3 –

Underground hall, surrounded by shops