Religion in the Wieliczka Salt Mine

Wieliczka, Poland

Wieliczka, Poland

The Wieliczka Salt Mines are situated near Krakow in Poland. Created during the Middle Ages, they were active until the beginning of the 21st century. After extracting the salt, the miners let a layer of salt form a shell to avoid the collapse of the rooms. The result were monumental halls that came to be used as underground chapels.

From the 17th century, the miners carved out statues depicting saints and biblical scenes in these underground halls. Some rooms also celebrated the royal family, like the chapel for the Queen Kinga. All rooms were illuminated by gigantic chandeliers, also carved out of salt. As far as is known, over the centuries, two large services took place each year: the celebration of the ‘Day of the Miner’ on December 4th, and Christmas mass a few weeks later.

The beginning of Communism in Poland in the early 20th century is marked in the mines too. Once the Communists took control, the miners were encouraged to ‘explore other themes’. Accordingly, they sculpted fantastical figures like gnomes and fairies. Nonetheless, the religious gatherings in the mines continued; an act of underground resistance against the Communist regime.

All the chapels, sculptures and chandeliers were unpaid work; a type of praxis communis that the miners engaged in after their day job. According to Thomas H. Cook, ‘it is as if the miners who perfected this chamber were intent upon creating an underground Versailles.’1 Jean Le Laboureur, a French author, in turn compared the Wieliczka Salt Mines to the Egypt’s pyramids: ‘[the salt mines] are the proof of laborious activity of the Polish, while the [pyramids] constitute a testimony of the tyranny and of the vanity of the Egyptians.’2 Today, these underground chambers are highly valued polish heritage, and still form the backdrop for religious gatherings – another type of praxis communis.

1. Cook, Thomas H. “Even darkness sings: from Auschwitz to Hiroshima: finding hope in the Saddest Places on Earth”. First Pegasus Books Hardcover ed. New York: Pegasus, 2018. Print. (P.311-312)

2. Długosz, Alfons. “Salines De Wieliczka = Salines of Wieliczka = Das Wieliczka’er Salzwerk”. Wiliczka: Muzeum Żup Krakowskich, 1963. Print. (P.5)

Author: Pierre Eichmeyer

Cook, Thomas H. Even darkness sings: from Auschwitz to Hiroshima: finding hope in the Saddest Places on Earth. First Pegasus Books Hardcover ed. New York: Pegasus, 2018. Print. (P.306-316)

Długosz, Alfons. Salines De Wieliczka = Salines of Wieliczka = Das Wieliczka’er Salzwerk. Wiliczka: Muzeum Żup Krakowskich, 1963. Print.

Berniard, .. Observations sur les mines de sel gemme de Wieliczka en Pologne. Paris: [s.n.]. Print.

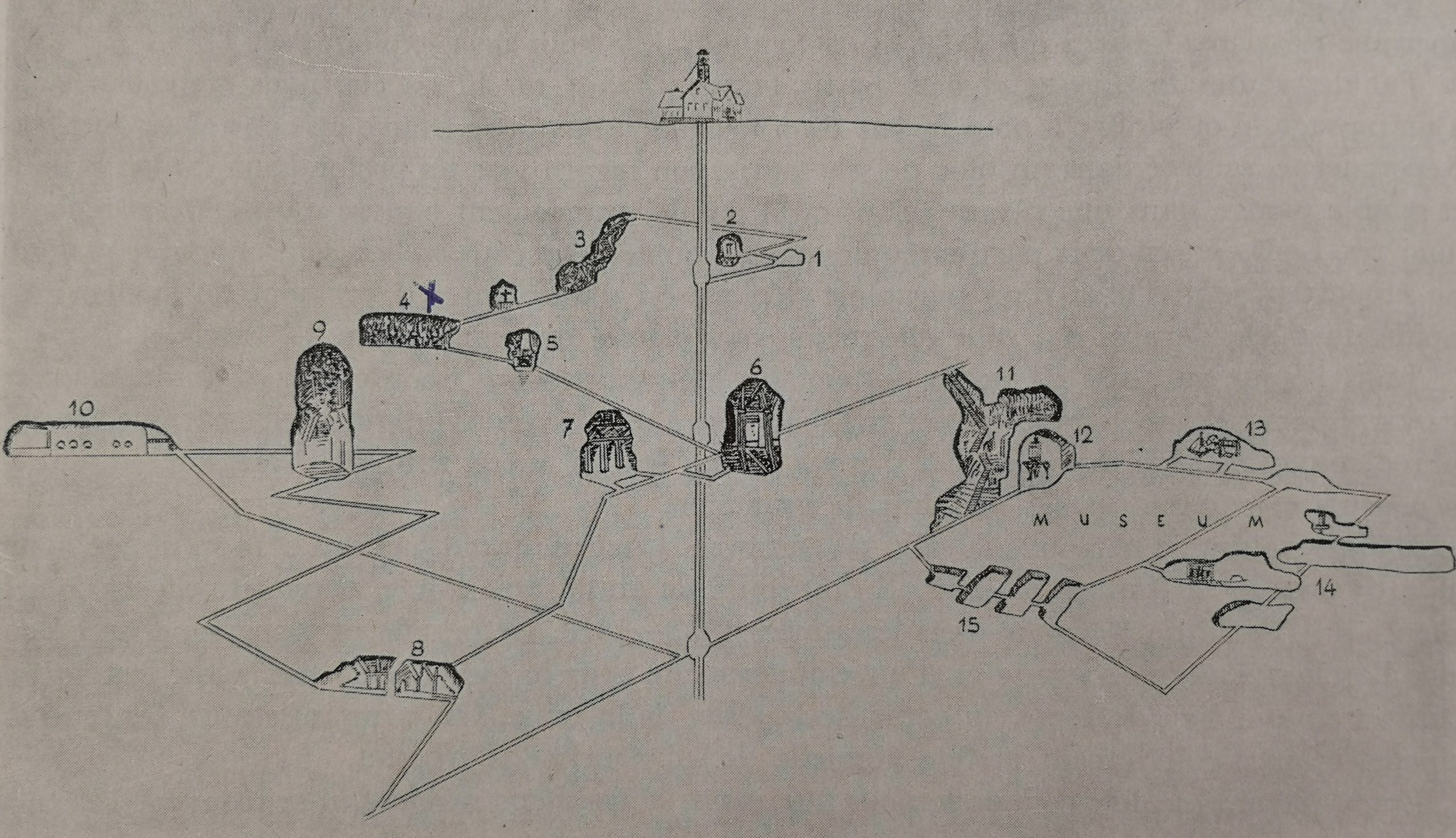

Image 1 –

Plan of the mine.

Długosz, Alfons. ‘Salines De Wieliczka = Salines of Wie-liczka = Das Wieliczka’er Salzwerk‘. Wiliczka: Muzeum Żup Krakowskich, 1963. Print. (P.12-13)

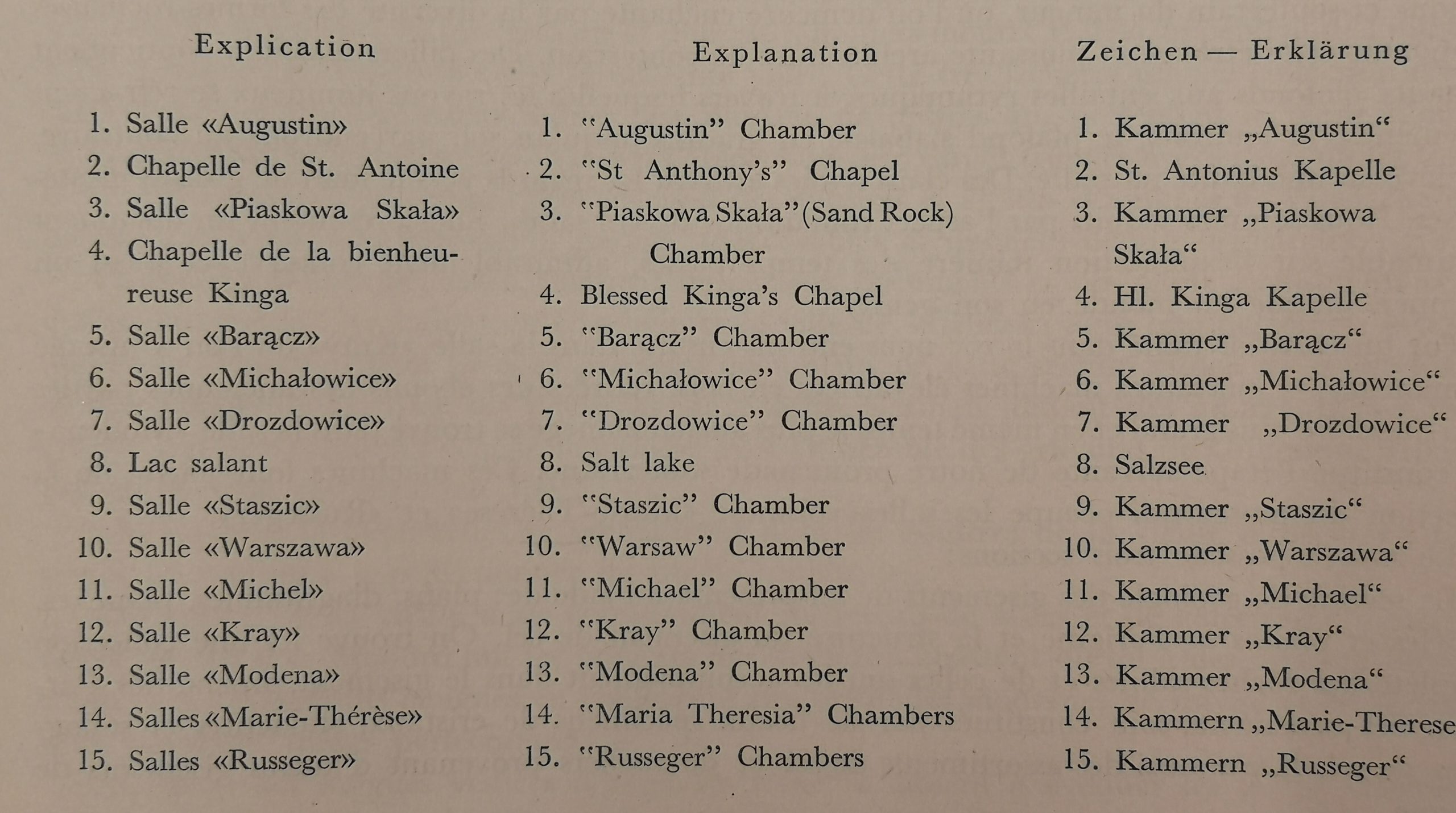

Image 2 –

Photography of a chandelier in a one of the chapels, showing different carved Bible scenes in the background.

Artist unknown. National Digital Archives of Poland, Illustrated Daily Courier, Illustration Archive, 1939/45

Image 3 – Photography of a service in the chapel of St. Kinga in honour to St. Barbara.

Maria, Berman. National Digital Archives of Poland, Illustrated Daily Courier, Illustration Archive, 12/04/1927