Production of Common Values within the Mineral Repository of Zurich

Nuolen Gravel Pit

Nuolen Gravel Pit

With the greater need for infrastructural facilities, such as expanding railway lines or road networks, gravel mining was introduced as a large-scale industry at the end of the nineteenth century. Almost at the same time, modernity introduced artificial stones such as concrete into the city’s construction, in which gravel served as an important aggregate material. The gravel pit in Nuolen, by Lake Zurich’s Obersee, started operations in 1926, and is still maintained today by the original company, Kibag AG. Kibag AG not only mines the gravel, but also transports and processes it, either as a foundation material for Zurich’s civil engineering office or as a component for the production of concrete for the city’s built structure.

The value of gravel as a loose transportable material is highly dependent on efficiently designed sorting and transport mechanisms to optimize the flow of material. The less gravel is handled, the more valuable it gets. Besides its financial value, its infrastructural value must be seen as crucial. It is everywhere, as the horizontal foundation of our buildings, roads and railways. The processed concrete is present in our city as the basic vertical structure of the buildings, but also as a facade material. The large-scale use of gravel creates a common habitat through its infrastructural indispensability for our built city. It is the basis for any kind of commoning in the city.

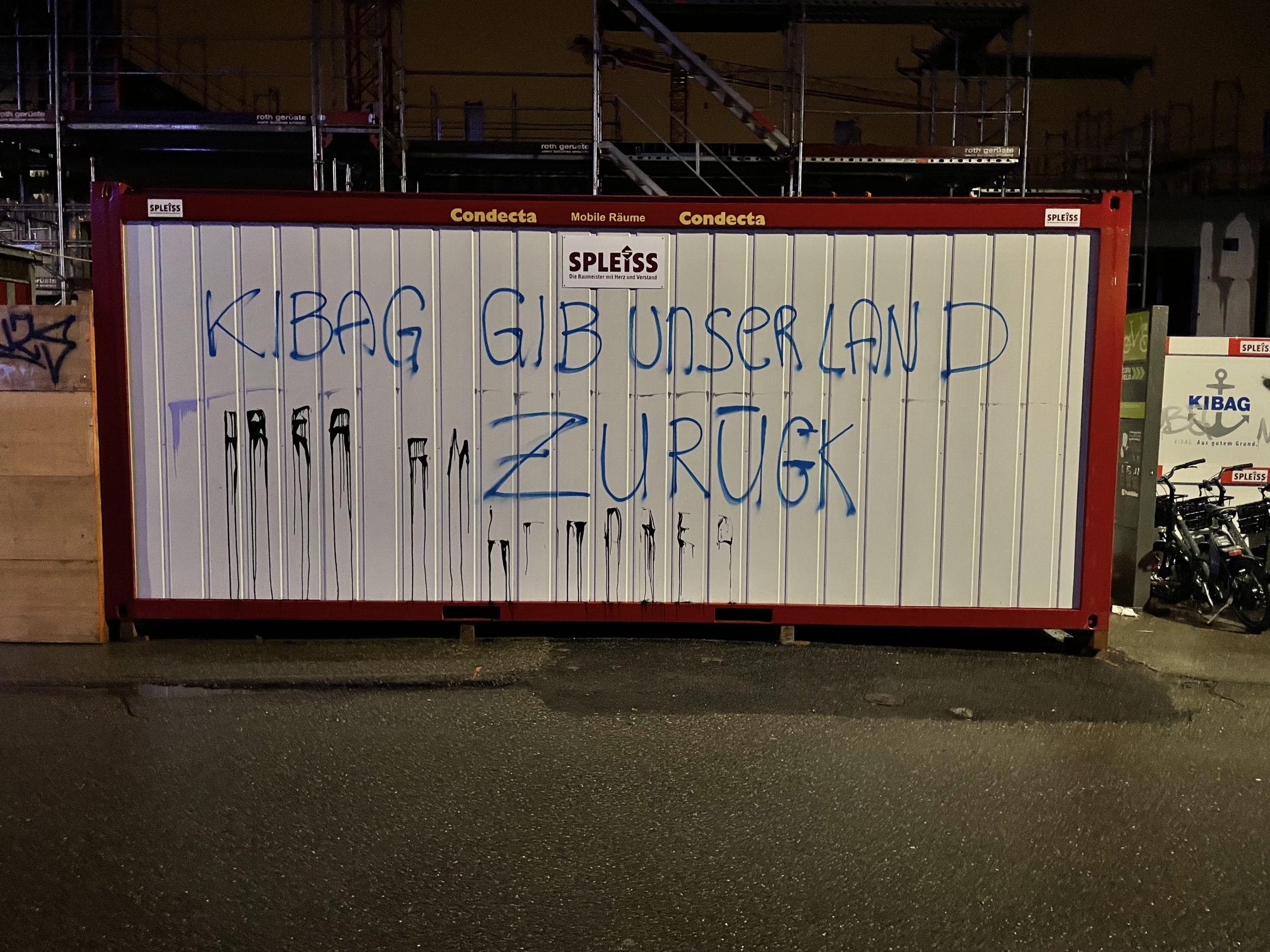

Common conflicts and negotiations occur if public and private interests are not the same common. The result is a balancing of interests between various aspects relevant to society in order to defend their right to a common-pool resource and their built common habitat. Through negotiating, the commons are created through social practice, acts of caretaking, and taking responsibility. Negotiations about the extraction of gravel from the pit and its return after the demolition of the built city occur due to ecological, political and juridical considerations.

Gravel and its impact on the ecological habitat after extraction is negotiated by residents, since dust and dirt affect the recreational and ecological qualities of the landscape and its nature. However, landscaping value can be achieved through the future development of the gravel pit. With increasing conflicts between nature, legislature, the neighborhood and public interests, the process of quarrying gravel becomes more difficult.

The city of Zurich is full of gravel, and must be seen as a mineral repository. We should start to reuse the material we already have within our city, keep it in a circular system within our building industry, and not strain the common-pool resource further. In order to re-evaluate the negatively associated gravel industry, gravel must be made visible within the city itself.

Kündig, Rainer. Die mineralischen Rohstoffe der Schweiz. Schweizerische Geotechnische Kommission, 1997.

Scapa. KIBAG 75 : 1926-2001. KIBAG, 2001.

Niggli, Paul, and Francis de Quervain. Die Bodenschätze der Schweiz. E. Rentsch, 1941.

Kibag Gravel plant Nuolen.Kibag Gravel plant Nuolen.

ETH Bildarchiv, Nuolen, 1973.

Kibag former gravel plant Nuolen.

Reiz, Nathalie, Kibag AG Nuolen, 2022.

Mixed demolition material of the city is crushed and reintegrated within the circular economy.

Reiz, Nathalie, Kibag AG Nuolen, 2022.

“Kibag give us our land back!”, public voice in a graffiti.

Reiz, Nathalie, Zurich, 2022.

Transported material from the Alps by glacial moraines are reshifted in order to build our cities during the Anthropocene.

Scapa. Kibag 75: 1926-2001. KIBAG, 2001.