Monte Testaccio

Monte Testaccio is an artificial hill in Rome formed from exclusively shard of approximately 80 million amphorae that used to hold olive oil in ancient Rome and deposited there during the first three centuries CE. Its usage and identity experience several transitions in the history, from the earliest urban environmental commons as public landfill to dispose amphora shard resulted from empire’s olive oil supply system, quarry for private and civil construction, cooling civic infrastructure for winery, civic terrain for secular and religious celebrations and to the latest heritage and knowledge common as an important archeological excavation site.

Tom Avermaete uses his tripartite notion of res communis, lex communis and praxis communis to articulate the material/immaterial basis, code and convention as well as the practice dimension of common resource. He also emphasizes the intertwined interaction among them and the complexity of different formal/informal agents. This theoretical framework fits also Monte Testaccio’s case and helps better understanding of the mechanism of its formation and transition, in which law and regulations (lex communis) plays especially a leading role, providing an insight to the life circle of common resource in a broader sense.

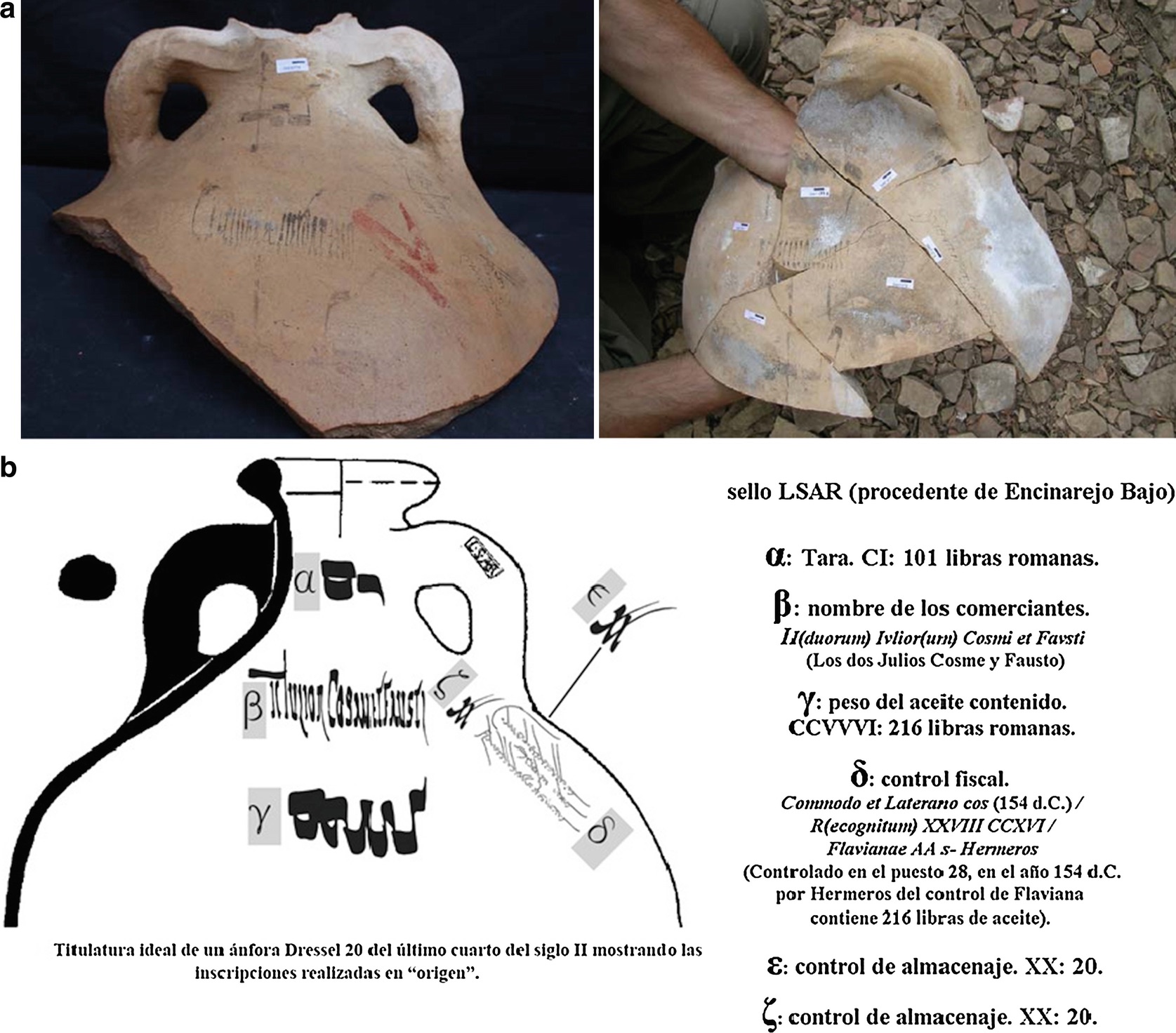

Lex communis is the genesis of Monte Testaccio. In formative phase, it started as an officially governed landfill near the warehouse area on the Tiber River to depose the olive oil amphorae in empire’s food supply system. Under supervision of local officers, they were carried to Monte Testaccio’s location, splintered in situ, carefully disposed into a ziggurat-liked structure with incline retaining wall made of bottom-less amphorae on each layer of terrace and then covered with lime because of landslide prevention and hygiene concerns. The clear structure with certain readable chronological sequence resulted from organized disposal, the unique composition exclusively of shard, together with the inscription and stamp on amphora, which were for the sake of control and contain valuable information of precise date, name of the producer, receiver of the oil and etc., promise the trash dump an afterlife. It is especially meaningful for the modern and contemporary archaeological study, because it provides a mean to decode the economic and administration system of the Roman Empire. Archeologists also use the shard to establish a database for larger investigation of inscription found in other archeological excavation. The landfill becomes an archive written on the pottery.

Monte Testaccio’s transition from a landfill into finally an archeological site is a history in which public management and private appropriation coexist. And lex communis is the mean of preservation and negotiation in this process. It keeps modifying itself to fit new and more valuable usage of the monadnock. Two moments are representative for that: One was the communal edicts and orders in 1772 and 1774 to prohibit excavation for construction material after Monte Testaccio became cooling infrastructure for winery storage and civic terrain for activities like carnival and reenactment of the Passion. The other was to limit its accessibility to the public and issue strict protective ordinance for construction and renovation in the whole area in the 1950s after its archaeological value was fully realized by the authority.

Rodríguez, José Remesal. “Monte Testaccio (Rome, Italy).” Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Ed. Smith C. Springer, Cham, 2019.

Ezban, Michael. “The Trash Heap of History.” Places Journal, https://doi.org/10.22269/120501, 2012. Accessed 25 Oct 2020.

Vos, Anna, “Testaccio: Change and Continuity in Urban Space and Rituals,” Urban Rituals in Italy and the Netherlands. Ed. Heidi de Mare and Anna Vos. Van Gorcum, Assen, 1993

Image 1 –

Shard of amphorae are disposed in a systematical way, forming a ziggurat-liked structure with 45-degree incline retaining wall

Rodríguez, José Remesal. “Monte Testaccio (Rome, Italy).” Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Ed. Smith C. Springer, Cham, 2019

Image 2 –

Restaurant at foot of Monte Testaccio utilizes its cooling effect

Rodríguez, José Remesal. “Monte Testaccio (Rome, Italy).” Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Ed. Smith C. Springer, Cham, 2019.

Image 3 –

Restaurant at foot of Monte Testaccio utilizes its cooling effect

Ezban, Michael. “The Trash Heap of History.” Places Journal, https://doi.org/10.22269/120501, 2012. Accessed 25 Oct 2020