Allotment Garden Juchhof

The Role of Allotment Gardens in Zurich

The Role of Allotment Gardens in Zurich

In my research, I tried to understand the role of allotment gardens in the city of Zurich. To investigate this issue, I chose the allotment garden of Juchhof, between Altstetten and Schlieren – on the outskirts of Zurich. Although allotment gardens officially exist in Zurich since 1915, the Juchhof created in 1947 was the first garden, which was conceptualised as a “Dauerareal” – meaning the ground was not lent by the city on a temporary basis, as it was the case for the previous gardens. This followed a law, which the planning bodies of Zurich passed in 1945, where they acknowledged the important role the gardens played in the city.

The tenants of allotment gardens organize themselves in associations, which date back to 1915. The association had the purpose to serve as a mediator between the needs of the tenants and those of the ground-owner, the city. Since 2008, the Grünstadt Zürich takes on this role. They also publish the Kleingartenordnung (KGO), which is the regulatory framework that needs to be followed in order to keep the garden. The associations still play an important role in organising social events or the shared facilities.

As the city expanded and developed dense housing typologies, demand for allotment gardens rose. The garden also came under pressure due to new large-scale infrastructural projects such as the Highway N1, the water-treatment plant “Werdhölzli”, and the composting facility. Although the existence of the garden was protected by law, it had been compressed and lost many of its shared and public spaces.

The possibility for the tenants to build their own hut, extend and decorate it, design their own garden, and place elements inside it allows for appropriation of the land. Of course, regulations limit the scope of possibilities, but they also urge the tenants to maintain the plots in an aesthetically acceptable state. I would argue that through the self-imposed, yet instructed maintenance task a strong identification between tenants and the rented ground and buildings happens. The changes often explicitly or implicitly serve as means of self-expression.

The Right to the City

David Harvey, 2008, New Left Review, Issue 53, pp. 1-22

A Black Box? Architecture and Its Epistemes

Tom Avermaete, unpublished, The Tacit Dimension, Architectural Knowledge and Scientific Research

A Narrative Approach to Collective Spaces: Urban Analysis and the Empowerment of Local Voices

Scheerlinck Kris, 2017, Oase, vol. 98., pp. 63-72

The Creation of the Urban Commons

David Harvey, Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, Verso. 2012, pp. 67-88

Institutions for Collective Gardening: A Comparative Analysis of 51 Urban Community Gardens in Anglophone and German-Speaking Countries

Göttl, I., & Penker, M., 2020, International Journal of the Commons, 14(1), pp. 30–43

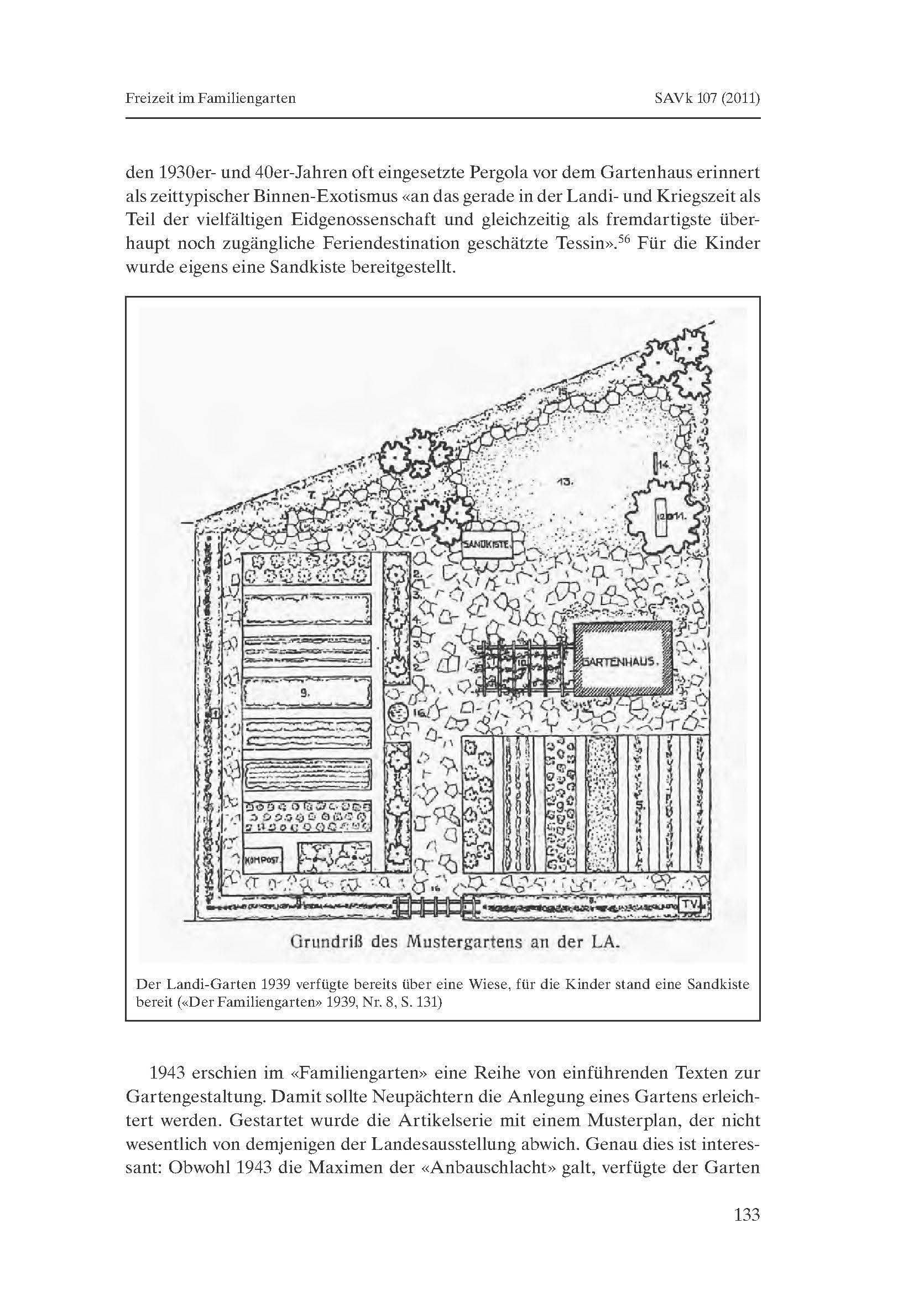

This depiction of an ideal garden in the magazine of the association shows how an allotment garden was supposed to be used. Most interestingly, the allocated space for leisurely use is much smaller in comparison to a typical garden of today in Zurich.

Magazine “Familiengarten”, 1939, Nr. 8/1939 (S.131)

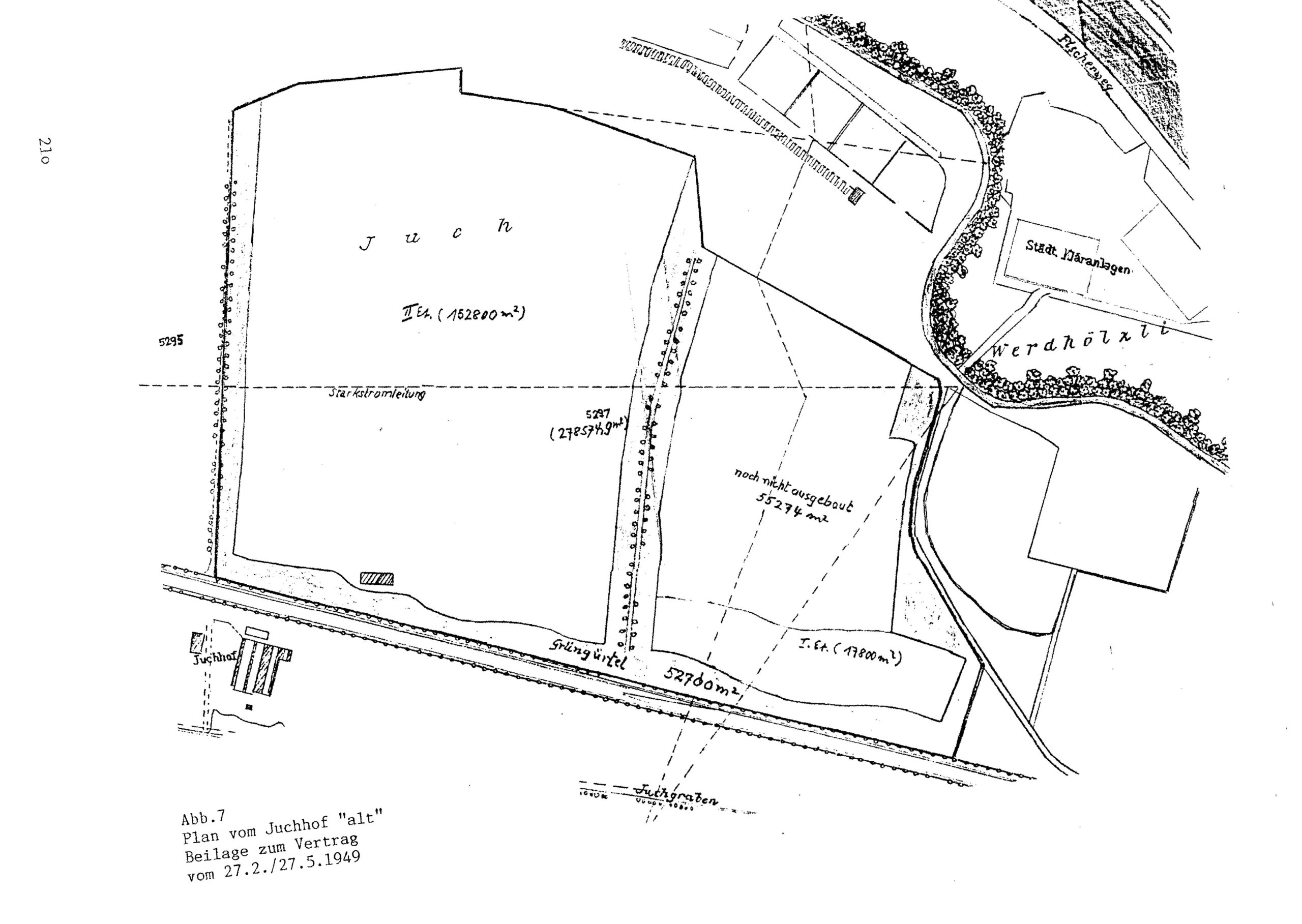

On this plan it can be seen how the Juchhof was originally conceptualised with large public alleys.

Association of Allotment Gardens Zurich, 1949, Swiss Social Archive